Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

How many chemicals are in use today?

EPA struggles to keep its chemical inventory up to date

by Britt E. Erickson

February 27, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 9

No one, not even the Environmental Protection Agency, knows how many chemicals are in use today. EPA has more than 85,000 chemicals listed on its inventory of substances that fall under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). But the agency is struggling to get a handle on which of those chemicals are in the marketplace today and how they are actually being used.

Under revisions made to TSCA last year, EPA is required to designate each of the chemicals on its TSCA inventory as either in “active” or “inactive” use by June 19. EPA also faces a June 19 deadline under the updated law to finalize the scope of its risk evaluations for 10 high-priority chemicals that the agency selected for review late last year.

As EPA works to meet these deadlines and implement other provisions required under the amended TSCA, the agency is finding significant gaps in its knowledge about chemicals in the U.S. market.

EPA’s lack of knowledge about chemicals in commerce was on full display during a public meeting on Feb. 14 intended to help EPA flesh out major uses for the 10 substances selected by the agency for risk evaluation. Stakeholders at the meeting from industry, environmental groups, and state governments pointed out uses that EPA did not consider for many of the 10 chemicals. In other cases, participants claimed that some of the 10 chemicals are no longer being produced in the U.S. or are not being used for certain purposes.

For example, 1,4-dioxane is no longer used as an ingredient in consumer products, reported Paul DeLeo, associate vice president of environmental safety at the American Cleaning Institute, an industry group. He encouraged EPA to update its website and statements to reflect that change, saying the current information is “confusing to consumers and overrepresents

Richard Morford, chief executive officer and general counsel of ENVIRO Tech International, the largest provider of solvents based on n-propyl bromide (NPB) in the U.S., criticized EPA for using outdated information on NPB, also known as 1-bromopropane. EPA claims that the solvent is used as an alternative to trichloroethylene for spotting and stain removal in dry cleaning.

Concerning chemicals

EPA is seeking use information for the following 10 chemicals so it can evaluate their potential risks to human health and the environment.

▸ Asbestos

▸ Seven solvents

▸ 1,4-Dioxane

▸ 1-Bromopropane, also known as n-propyl bromide

▸ Carbon tetrachloride

▸ Methylene chloride

▸ N-methylpyrrolidone

▸ Tetrachloroethylene, also known as perchloroethylene

▸ Trichloroethylene

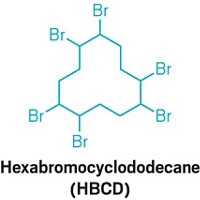

▸ A cluster of cyclic aliphatic bromide flame retardants

▸ Pigment Violet 29

Dry cleaners are no longer switching from trichloroethylene to NPB for spotting, Morford said. “They haven’t in years. The use of NPB in dry cleaning is virtually dead,” he told EPA. NPB-based “dry cleaning spotters and stain removers haven’t been manufactured since 2008 and don’t exist today.” Less hazardous spotting agents, including soy-based cleaners, glycol ethers, acetone, and blends of these substances, are now being used.

EPA gleaned its information on the manufacturing, importing, processing, distribution, use, and disposal of these and all other chemicals from publicly available information, including Chemical Data Reporting (CDR) and Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) data, as well as from data provided by manufacturers in premanufacturing notices required for new chemicals.

But, as many stakeholders at the Feb. 14 meeting pointed out, that information is far from complete and in some cases, out of date. For example, CDR information, which is required under TSCA, is typically submitted only by manufacturers who annually produce more than 11,340 kg of a substance at a single site. TRI data, which quantify releases of chemicals to air, water, and land from certain facilities, do not cover all industry sectors. In addition, some facilities are exempt from reporting.

Environmental groups are urging EPA to use its authority under the new law to request the missing data from industry. These groups are also asking the agency not to establish volume or sales thresholds or exemptions from reporting as it updates its chemical inventory. EPA will use the information to help prioritize chemicals for risk evaluation.

The scope of EPA’s first 10 risk evaluations will set the stage for how EPA conducts future evaluations of existing chemicals under the revised TSCA. The first step in the scoping process is to identify conditions of use for each of the 10 substances, said Tala Henry, director of EPA’s risk assessment division in the Office of Pollution Prevention & Toxics.

But as EPA is finding out, that is easier said than done. On the one hand, environmental and public health groups are urging the agency to consider all possible uses, including reasonably foreseeable uses that may not be intended by a chemical manufacturer. In contrast, industry groups are fighting back, saying it would be unworkable for industry and for EPA to assess every use, particularly for widely used chemicals such as solvents. Seven of the first 10 chemicals being evaluated by EPA are solvents.

EPA heard both sides of the debate at the Feb. 14 meeting.

Mike Belliveau, a senior advisor for Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families, a coalition of advocacy groups, urged the agency to “include all uses, all exposures, and all vulnerable populations” in its risk evaluations. A previous risk assessment for one of the 10 chemicals, N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP), examined only one use of the chemical—paint and coating removal—which accounts for less than 10% of the chemical’s use, he said.

Richard Denison, lead senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, also asked EPA to cast a broad net and consider imports as well as domestic products. “Even products that have been eliminated or shifted away from by domestic companies may still be imported,” Denison said. “We were able to purchase on the internet brake pads that contain asbestos,” he noted, adding that the product arrived unbagged in a flimsy box. “There is no indication on the website that they contain asbestos, although the shoe box has a very well-worn label on it indicating the presence of asbestos.”

“It is extraordinarily easy for anyone to buy consumer or commercial products containing the 10 chemicals,” added Jennifer McPartland, a senior scientist at EDF. The environmental group purchased several such products “with a couple of mouse clicks on Amazon or other retailer websites,” McPartland said. In addition to asbestos-containing brake pads, the group obtained NMP-based paint strippers, 1-bromopropane-based dry cleaning solutions, and insulation containing the brominated flame retardant hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD), she noted.

Other environmental groups suggested that EPA consider legacy sources of chemicals no longer used in most products, such as HBCD.

“Some historical uses of HBCD, such as consumer upholstery and textiles for furniture and cars, as well as cases for electronics like televisions,” have been phased out, said Daniel Rosenberg, senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “However, these uses are in long-lived consumer articles that are still contributing to current exposures and will continue to do so for years to come.”

Jen Coleman, health outreach director at the advocacy group Oregon Environmental Council, encouraged EPA to use state databases, such as the one created by Washington State, to get information about the presence of chemicals in consumer products. Washington State requires manufacturers of children’s products to disclose chemicals of concern, including five of the 10 chemicals that EPA is evaluating.

A quick scan of Washington’s database for pigments and dyes shows that they are in “everything from underwear to dishware to temporary tattoos,” Coleman said. EPA states that the only consumer uses for the pigment Violet 29 are in watercolor and acrylic paints. “I’m not confident that it is, in fact, a comprehensive assessment of the presence of Violet 29 in consumer products,” Coleman said.

Industry groups welcomed EPA’s attempt to pull together various uses for the 10 chemicals but cautioned the agency about using outdated sources. “Some of the sources of information EPA has used and cited are poor sources for current information, such as the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services household products database,” said Christina Franz, a senior director of regulatory and technical affairs at the American Chemistry Council. “This database is outdated and not kept current.”

EPA’s effort to document the uses for the 10 chemicals “is a good first step,” Franz added. But the documents “must be validated to ensure that the information contained within them is reliable and accurate,” she said. “That can really only occur through an iterative process to ensure that the agency has the most current and accurate understanding of the TSCA uses of these chemicals in commerce.”

That’s no small task, according to producers of the solvent NMP. Kathleen M. Roberts, representing the NMP Producers Group, claimed it would be unreasonable to expect any organization to provide manufacturing, processing, transportation, release, and exposure information for every product that contains NMP. “An information collection request for all conditions of use of NMP is a daunting task,” she noted, adding that NMP is a universal solvent used “in many, many industrial sectors in varied processes and to formulate a multitude of products.”

And not every use of such a widely used chemical is likely to carry the same risk. Several industry groups urged EPA to focus only on high-risk uses in its risk evaluations. In some cases, EPA already knows protections are in place to reduce the exposure, they argued. With only a few months left before EPA hits several statutory deadlines, the agency must use its discretion, they said.

The next four years will be critical for implementation of the new TSCA, said NRDC’s Rosenberg. It will coincide with a period when “crucial decisions will be made,” laying the groundwork for future evaluations under the revised law, he noted. Rosenberg and other environmental advocates urged EPA to resist pressure from all sources and focus on protecting public health and the environment.

CORRECTION: This story was updated on Feb. 28, 2017, to correct the title of Paul DeLeo of the American Cleaning Institute. He is the industry group's associate vice president of environmental safety.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter