Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Delivery

On-demand pain relief, triggered by light

Injectable material can be repeatedly stimulated with near-infrared light to release painkillers

by Prachi Patel

January 19, 2017

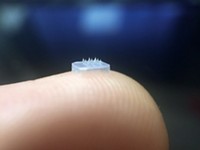

Once injected into the body, a new material can repeatedly release small bursts of local anesthetic when zapped by low-intensity, near-infrared light for one minute (Nano Lett. 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03588). The material’s developers, who have tested it in rats, say the on-demand system could make pain management safer and more effective, and give patients more control.

People suffering from chronic or post-surgical pain are typically prescribed narcotics or given anesthetic shots to dull pain. But both have drawbacks: Narcotics can be addictive, while anesthetics don’t last long and injecting the right dosage at the site of pain can be a challenge.

To improve control over anesthetic delivery, scientists have encapsulated drugs in liposomes, hollow sacs made of phospholipids, which are leaky enough to release a drug slowly over a period of time. “The problem is, there’s no way to turn it on and off,” says Daniel S. Kohane of Harvard Medical School.

So in 2015, Kohane and his colleagues made liposomes that can be controlled from outside the body with tissue-penetrating near-infrared light. The researchers decorated the liposome surface with gold nanorods, which absorb near-IR and generate heat. The heat expands the phospholipid membrane, making it more permeable so that some of the particle’s payload escapes quickly. The liposomes needed 10 minutes of light exposure to release their payload (Nano Lett. 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03440). But high intensity or long irradiation time can cause tissue burns, Kohane says.

To make particles that are triggered in just a minute or two with lower intensity light, the researchers add a new lipid to the membrane: 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (MSPC), which can break free of the membrane when heated by the gold nanorods. The researchers speculate that this process opens up pores that allow a greater portion of the payload to be ejected than from a membrane without MSPC.

In benchtop experiments, when they loaded the little lipid sacs with the nerve blocker tetrodotoxin and shined near-IR on them for a minute or two, the drug flowed out of the particles. The release stopped after a few hours once the particle wall cooled and tightened up again, but could be repeated with additional light bursts that cause more MSPC molecules to break free of the membrane. This could provide the basis for an on-demand drug delivery system to address pain, Kohane says.

The researchers tested the system by injecting the liposomes into the footpads of rats. They shined near-IR light at a high enough intensity to penetrate the skin but below what would cause tissue damage on the footpad for a minute. Then they poked the footpads every half hour. Treated animals indicated no pain for the first two hours, after which the effect began wearing off. Full pain response returned after six hours. The researchers also used the material to repeatedly block one leg’s sciatic nerve so that test animals lost sensation in that leg.

“This is an impressive application for light-induced drug delivery,” says Jonathan F. Lovell, a biomedical engineer at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Although the technique would be limited to nerves located no more than a few centimeters under the skin, it would allow doctors to fine-tune the doses for nerve blocking, he adds. “The current standard of direct injection can have highly variable results, which you know if you’ve ever had a gum numbed at the dentist’s.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter