Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

DNA

Measurements heighten mystery of D-amino acids in the brain

Missing D-glutamate in mice brains hints at undiscovered enzymes

by Louisa Dalton

March 29, 2017

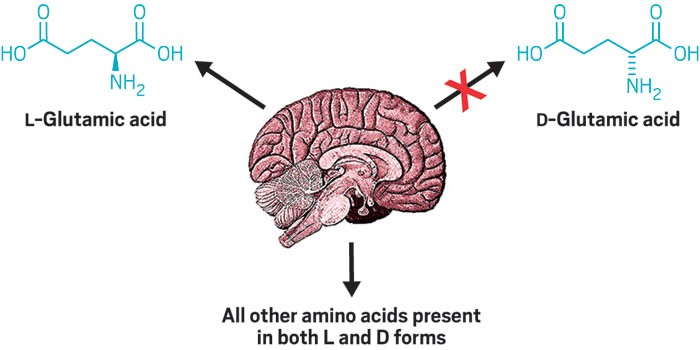

Right-handed amino acids—found in small doses in nature—are largely a mystery. In humans, most linger at low concentrations yet play unknown roles in the body. A new survey of right- and left-handed amino acids in the mouse brain thickens the plot. The study’s findings imply that the brain tightly regulates the levels of right-handed amino acids and hint at undiscovered enzymes that flip lefties to righties (ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00398).

Ubiquitous left-handed L-amino acids serve as the building blocks of all proteins. However, their mirror images, right-handed D-amino acids, are rarer and more perplexing. Their purpose in humans was unknown until 2000, when scientists figured out that one of them, D-serine, is a neurotransmitter. Many researchers think the presence of other D-amino acids in the brain and body suggests that they must have significant functions, too. To find those functions, though, requires baseline surveys that determine normal levels of D- and L-amino acids in various parts of the body, says Daniel W. Armstrong at the University of Texas, Arlington.

Armstrong’s group collaborated with Adam L. Hartman’s laboratory at Johns Hopkins University to measure baseline values for D- and L-amino acids in the cortex and hippocampus of mice, brain areas of interest because of Hartman’s previous work on epilepsy. The collaborators separated blood from brain tissue and then purified and fluorescently tagged the amino acids in the samples. They measured the amino acids by separating the D- and L-varieties with highly sensitive chiral columns and then detecting the fluorescent peaks.

“Many curious things turned up,” Armstrong says. Most D-amino acid levels were 10 to 2000 times as high in the brain as in the blood for the 12 amino acids measured. The concentration of the neurotransmitter D-serine, near 0.05 μg per mg brain tissue, was among the highest, but D-aspartate and D-glutamine were even higher. Such quantities suggest neural roles for many of the D-amino acids, Armstrong says.

Particularly striking was the conspicuous absence of D-glutamate anywhere in the brain or blood. L-glutamate is the most abundant amino acid in the brain, so Armstrong expected to see at least some D-glutamate. Yet his team couldn’t detect it at all with a detection threshold of 0.00005 μg per mg tissue.

The unexpected absence, Armstrong says, implies that the body keeps D-glutamate low for a physiological reason. It also implies that the brain has a mechanism for efficiently removing D-glutamate or keeping it quite low compared with everything else.

Armstrong surmises there may be undiscovered enzymes at work. A known enzyme converts D- and L-glutamate to D- and L-glutamine, so perhaps a stereoselective enzyme takes only L-glutamine back the other way, making D-glutamine a sink for D-glutamate, he says. High brain levels of D-glutamine support that theory, Armstrong says.

Or, Herman Wolosker of Technion Israel Institute of Technology suggests that the brain may also lack transporters that recognize D-glutamate, so it cannot be imported from the blood into the brain.

Other findings from the study raise the specter of ghost enzymes, too: Wolosker points out that for some of the less abundant amino acids, relatively high fractions exist in the D-form. Isoleucine, for instance, is 24% right-handed in the hippocampus. “It points to the possibility of additional enzymes in the brain that transform L- into D-amino acids,” he says.

For the moment, Armstrong and his group are concentrating on pinning down the role of D-amino acid oxidase, an enzyme known to degrade D-amino acids, in particular D-serine. By repeating the baseline study in mice lacking the gene for D-amino acid oxidase, the scientists hope to elucidate what other D-amino acids it regulates. They are also conducting a D-amino acid survey on human blood and are curious to see whether D-glutamate goes missing there too.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter