Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Burning Iranian oil tanker raises environmental concerns for China’s coast

Potential spill could be 3 times as large as that from the Exxon Valdez

by Glenn Hess

January 11, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 3

An Iranian tanker carrying 150 million L of oil partially exploded and has been on fire in the East China Sea since Jan. 6, following a collision with a cargo ship about 160 nautical miles (300 km) east of Shanghai.

Thirty-two crew members were aboard the vessel. One body has been recovered, and the fate of the remaining crew is unknown.

Beyond the immediate concern about the crew, “We are worried about the potential environmental impact that could be caused by leakage from the vessel,” says Rashid Kang, campaigner at Greenpeace East Asia. No large-scale oil spill had been reported by C&EN’s deadline.

The tanker, a Panama-flagged vessel owned and operated by National Iranian Tanker, was ferrying highly flammable condensate, a type of ultralight crude oil, to South Korea’s Hanwha Total Petrochemical.

By comparison, the Exxon Valdez was carrying 200 million L of crude oil when it spilled 41 million L into Prince William Sound off Alaska in 1989, contaminating 2,000 km of coastline.

The term condensate describes a range of light crude oils that occur primarily as a by-product of natural gas production. They are usually composed of propane, butane, and pentane and also have high concentrations of benzene and hydrogen sulfide.

Petrochemical companies use condensate as a feedstock to manufacture various plastics. Refineries use condensate to produce vehicle fuels, such as gasoline and diesel.

China’s transport ministry said Jan. 9 that the condensate was burning off or evaporating, reducing the chances of an environmentally destructive oil slick forming off China’s coast, according to the state-run People’s Daily newspaper.

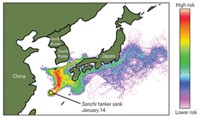

Condensate does tend to evaporate quickly, confirms Simon Boxall, a principal teaching fellow at the National Oceanography Centre Southampton at the University of Southampton. “This is fine while the winds remain westerly and blow the contaminated atmosphere and waterborne plumes away from the coast. But the story could change quickly if the winds change,” Boxall says.

And condensate is even more combustible than heavier crude, raising concerns that the tanker could break up and sink unless the fire is brought under control.

If the ship were to sink, the highly toxic condensate “will seep slowly into the ocean, providing a chronic pollution source for some considerable time, and will seriously damage the immediate environment,” Boxall tells C&EN.

In addition, he says plankton and fish will accumulate the waterborne toxins and spread beyond the immediate vicinity, creating the need for a fishing ban in the region and regular monitoring to ensure the contaminated area is sufficiently defined.

The best option for the environment, Boxall says, is to extinguish the fire, secure the vessel, and tow it to safe harbor so the oil can be removed. “Plan B would be to flame off the oil at the surface. That’s fine as long as this doesn’t cause an explosion and the ship then sinks,” Boxall says.

Spills of condensate have been very rare, so there isn’t much data or protocol for dealing with them. “The material is more soluble in seawater than the heavier crude. This means that the surface slick mixes with the seawater better than heavier crude and is more difficult to separate,” Boxall explains. “We don’t really have an effective way of removing light crude from the ocean.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter