Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Weed scientists brace for a second year of dicamba use

Drifty pesticide caused damage and controversy last year, but new restrictions may help

by Melody M. Bomgardner

January 22, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 4

In many midwestern soybean fields, a plant called Palmer amaranth is enemy number one. This B horror movie of a weed can grow more than 15 cm in a week. It steals sunlight, water, and nutrients from slower-growing soybeans. An individual plant can produce 100,000 seeds and grow thick enough to bust a tractor.

So it was more than inconvenient when the best solution for controlling Palmer amaranth turned out to be enemy number two.

New formulations of dicamba herbicide introduced last year by Monsanto, BASF, and DuPont were excellent at controlling amaranth in fields of soybeans engineered by Monsanto to be tolerant to the herbicide. But farmers filed thousands of reports alleging the herbicide drifted off target, damaging nontolerant soybeans as well as trees, tomatoes, and other plants.

The reports of damaged crops prompted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to change the label instructions on the chemical, such as lowering the wind speed allowed for application. Minnesota, Missouri, and North Dakota imposed additional restrictions. And in Arkansas, the state plant board ruled that farmers cannot use the chemical after April 15, the end of the planting season, though it faces a lawsuit from Monsanto and pushback from the state legislature.

Though the restrictions make using dicamba more complicated, many farmers will be spraying the controversial herbicide on at least some of their fields this year. Monsanto expects sales of its dicamba-tolerant soybeans to double to over 16 million hectares, an area almost the size of Wisconsin. And the company is building a new dicamba manufacturing plant in Luling, La.

Farmers have little choice but to use it, particularly in regions where Palmer amaranth and its weedy cousin water hemp have become resistant to glyphosate and other mainstay herbicides. Still to be seen is whether the new rules for applying dicamba will reduce the incidence of off-site damage.

By the end of the 2017 growing season, state departments of agriculture from Mississippi to Minnesota had racked up over 2,700 cases of suspected dicamba injury totaling about 1.5 million hectares, according to Kevin Bradley, professor of plant sciences at the University of Missouri.

Initial tallies of the soybean harvest by the U.S. Department of Agriculture suggest that the damage did not result in an overall decrease in yield. Weed scientists say mild weather during the growing season and well-timed rainfall helped damaged plants recover.

Still, scientists who work with farmers are concerned about what they see as chemical trespass. Last year, after investigating reports of injury, university and extension agent weed scientists said the new dicamba formulations don’t stay put. They can volatilize and move to other fields hours or even days after application.

The herbicide companies strongly disagreed and said they successfully stabilized dicamba with techniques such as adding a salt to the molecule to reduce volatility. They maintain that the nontolerant soybeans were victims of incorrect grower application and that training and use of specific equipment would solve the problem.

Neither side has changed its mind since the end of last year’s growing season. “There are several things we can do to minimize risk, but it’s hard to do that when volatilization is not acknowledged,” says Jason Norsworthy, professor of crop, soil, and environmental sciences at the University of Arkansas.

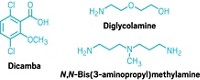

Not using dicamba at all is not an attractive option either. “We desperately need this technology. We’re down to two modes of action for water hemp and Palmer amaranth,” Norsworthy says, referring to dicamba and glufosinate, sold by Bayer as Liberty. The herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) can also be used, but it relies on the same mode of action as dicamba.

Norsworthy conducted field trials to determine if Monsanto’s XtendiMax and BASF’s Engenia dicamba products could migrate even after spraying was complete. He compared the new formulations with older versions that weren’t designed for reduced drift.

What he found was not reassuring. The least volatile of the old herbicides is a diglycolamine salt of dicamba called Clarity.

“When we looked at Clarity versus XtendiMax and Engenia, we saw really no reduction in volatility based on the amount of symptoms we saw in soybean—not just in my trial but in six trials done by others,” Norsworthy says. Dicamba-injured soybeans have distinctive cupped and wrinkled leaves and stunted growth.

Soybeans are very sensitive to dicamba, which ironically makes them a great sensor for research on chemical movement. In tests conducted in five locations across the U.S., Norsworthy saw dicamba damage nontolerant soybeans that had been covered by buckets until 30 minutes after spraying. Healthy soybean plants that he moved from a greenhouse into a field 24 hours after spraying were also injured.

In one location, Norsworthy observed a change in wind direction six hours after spraying. A wind that was coming from the east shifted to coming from the south. “What we observed was considerable damage on the north side of the field that was as bad or worse as what occurred on the west side,” he says. Damage on both sides suggests it came from volatilization “quite a while after application.”

BASF is sticking to its story. “Based on years of R&D, we don’t believe volatility is a driving factor,” says Scott Kay, vice president of the company’s crop protection division. “We identified multiple contributing factors and don’t believe volatility is one of those contributing factors.”

BASF and Monsanto point out that EPA has designated the new dicamba formulations as registered pesticides. That means applying them requires a pesticide license and dicamba-specific training. Growers will be given an application checklist by the companies covering everything from when and how much they can spray to proper equipment and weather conditions. Kay advises farmers to understand what crops are growing in nearby fields and talk to their neighbors.

BASF’s customers are thrilled with Engenia, Kay maintains. “Many we have heard from say they have experienced their cleanest fields ever,” he says. A survey the company conducted shows farmers rate the product 8.6 out of 10 and say they expect to buy and use it again.

In states other than Arkansas, farmers will be able to continue using dicamba during the growing season. But warmer temperatures will make dicamba more volatile, weed experts caution.

Robert Hartzler, an extension weed scientist and professor of agronomy at Iowa State University, hopes farmers can wrap up dicamba spraying in early June in his state. “I think people now realize how careful they need to be with the product—that will obviously help out quite a bit. Our big concern is that due to unpredictable weather, people will be forced into applying the products when there is a high risk of off-target movement.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter