Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

The late Paul Allen leaves $125 million for immunology research center

The third Allen Institute will track the immune systems of healthy people, and those with autoimmune diseases

by Ryan Cross

December 13, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 49

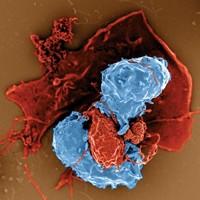

Microsoft cofounder Paul G. Allen, who died from complications of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in October, is expanding his legacy in life-science research with a $125 million donation to launch the Allen Institute for Immunology. The center, which will recruit about 70 scientists to study the human immune system in health, autoimmune disease, and cancer, will join the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the Allen Institute for Cell Science in Seattle.

Those other institutes focus on bold initiatives—like brain maps and cell atlases—that would be too large for a single academic lab to tackle. Soon after the cell science institute launched in 2014, Allen created a $100 million biomedical research fund to sponsor other risky, but potentially rewarding, research projects.

“At the time, the immune system kept coming up as an area that was really ripe for the kind of things that we do,” says Allan Jones, CEO of the Allen Institute. Allen ultimately decided that immunology was important enough to have its own dedicated institute.

Unlike the brain and cell institutes, which seek to uncover gaps in scientists’ understanding of how the brain and cells work, the immunology institute will pair basic science with clinical research right off the bat. “You are hard pressed to study the human immune system and not get very close to disease in a hurry,” Jones says.

Jones recruited Thomas F. Bumol, a former vice president of biotechnology and immunology research at Lilly Research Laboratories, to lead the new institute. Since it doesn’t have a clinic of its own, Jones and Bumol have picked five academic and medical centers to partner with them in their initial plan to study the immune system in five diseases.

Three of these diseases—rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease—are conditions in which the immune system is in overdrive. The other two—multiple myeloma and melanoma—are cases where the immune system fails to spot and kill cancer cells.

In parallel with the disease studies, the institute is planning longitudinal studies of healthy people to understand what a baseline immune system looks like and how it fluctuates during a normal year of life. Bumol says the institute will collect frequent blood and microbiome samples from three age groups: 4-year-old children, 25- to 35-year-old adults, and 55- to 65-year-old adults.

The institute doesn’t have plans for drug discovery or development, but Bumol thinks the group’s projects will complement work done at drug companies. For instance, the clinical partners will make detailed cellular, genetic, and molecular measurements of their patients’ immune systems—similar to the measurements made in the longitudinal studies—to parse why some people respond well to certain therapies and others don’t.

One of the institute’s clinical partners, Stanley Riddell from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, will provide tissue samples from people with multiple myeloma, possibly including those in a clinical trial involving a Celgene CAR T-cell therapy. CAR-T cell therapies, which use genetically-engineered versions of a person’s own immune cells to target and kill their cancer, have been life-saving for some people. But others aren’t helped at all or have a positive response at first, only to find their cancer roars back later. Riddell hopes that detailed monitoring of his patients’ immune systems will help explain this variability.

Advertisement

This data collection phase is somewhat vague but is intended to keep research options open. “It is a little bit hard to predict what we might learn, and I would assume that some of the things that we hope to learn won’t turn out to be the most important,” Riddell says. “If we knew exactly what we could get out of this, it wouldn’t be as much of an interesting project.”

The new institute is more than an immunological data dump, however. “Paul Allen’s admonition to us was to go well beyond descriptive, cool, correlated data,” Bumol says.

Indeed, the ultimate goal is to understand the immune system well enough to quickly spot when it’s out of tune and learn how to coax it back into shape. “The time has come for the immune system to be front and center as one of the key disciplines of medicine,” Bumol says.

CORRECTION:

The photo's caption was updated on Dec. 13, 2018. The photo was not taken last year as previously stated.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter