Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Cancer

Cancer cells can evolve by combining

When cancer cells fuse, they combine genetic materials, increasing diversity

by Laura Howes

January 23, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 3

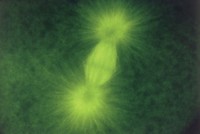

Cancer cells are notoriously tricky; despite treatments designed to kill them, they can keep returning by quickly evolving or diversifying their genetics. Mutation is one way that cancer cells can switch up their genetics. Now, a group led by Andriy Marusyk of the University of South Florida has found another mechanism, one that looks a lot like sex. In in vivo and in vitro tests, Marusyk’s team found that a small number of cancer cells can combine their DNA by fusing together, taking on characteristics of both parent cells (Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, DOI: 10.1038/s41559-020-01367-y). Researchers have seen cancer cells fuse before, but it wasn’t clear if there was a benefit to the cells. Marusyk’s team wondered if parasexual recombination—combining two cells to create one new one—might be happening. To find out, the researchers made two populations of breast cancer cells, each modified to produce a different fluorescent label. Using microscopy, the researchers saw cells combine, creating cells with both colorful tags. Some of those double-tagged cells resulted from processes such as one cell engulfing another, while other times two cells fused to produce a new, genetically different cell. The team cultured the new cells and found they could multiply and proliferate, passing on new traits. The researchers’ modeling suggests this type of genetic recombination could promote evolution in cancer cells. Further research is needed to understand if this new mechanism could complicate treatment plans or be clinically relevant in other ways, the team says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter