Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Microbiome

Baby poop may hold a secret to food allergies

Mice develop a milk allergy when given fecal transplants from allergic babies, suggesting some gut microbes may help protect against the condition

by Megha Satyanarayana

January 22, 2019

An experiment involving the odd combination of mouse guts and baby poop may help us understand why some infants develop food allergies and others don’t.

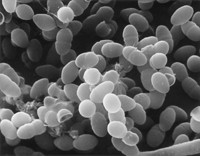

A team of researchers, led by Cathryn Nagler at the University of Chicago, made mice allergic to milk simply by giving the animals a fecal transplant from human babies with the allergy (Nat. Med. 2019, DOI: 10.1038/s41591-018-0324-z). The findings suggest that particular classes of gut bacteria may protect mice, and people, from developing food allergies.

Some food allergy experts think the experiment is quite the feat. “It’s shocking, to be honest,” that transferring the microbiome gave mice an allergy, says Kari Nadeau, who studies food allergies at Stanford University School of Medicine.

Nagler has been studying the role of the infant microbiome in food allergies for years. She and other experts in the field say that the incidence of food allergies in people has been increasing at a rate that suggests the conditions don’t have a genetic origin, but rather an environmental one. Previously, Nagler and collaborators compared the microbiomes of healthy and milk-allergic infants and found “an enormous difference,” she says, “even at just four to five months of age.”

To study the microbiome-allergy connection further, Nagler and her team gave mouse feces from formula-fed infants who were either allergic to milk or were not. The researchers fed the animals their normal food, but included the formula that the babies were drinking, in the hopes that the presence of the human diet would incentivize the bacteria to colonize the mice’s intestinal tracts.

When the scientists then fed the mice a milk protein that causes allergy in humans, the mice receiving the allergic infant transplants showed signs of an allergic reaction, including those of anaphylaxis. The mice receiving the healthy transplants did not.

The team analyzed the bacterial contents of the donor feces and found some stark differences. Members of the Clostridia class of bacteria were more prevalent in the stool from healthy babies compared with feces from allergic babies. One species in particular, Anaerostipes caccae, was less detectable in the allergic baby stool. Bacteria like A. caccae have been tied to keeping the immune system in check in the part of the small intestine where food is absorbed, Nagler says.

Nagler says her team is trying to figure out why A. caccae is missing in children with milk allergies. “That’s the million dollar question,” she says. Is it the absence of bacteria that causes the allergy, or does the allergy somehow lead to the loss of beneficial bacteria?

Advertisement

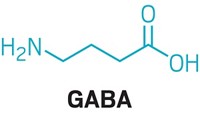

Going forward, Nagler thinks the ability to give mice a milk allergy through fecal transplants will provide researchers with a model to help them investigate possible therapies for the condition. But both Nagler and Nadeau point out that giving allergic infants transplants of feces from healthy babies is not on the horizon, mainly for safety reasons. Researchers still don’t know if a friendly bacterial species in one gut could cause disease in another. Instead, Nagler says, her team wants to test restoring metabolites from the missing bacteria. For A. caccae, that metabolite is butyrate, which is used by the cells lining the intestine as a source of energy.

“I think it’s important to keep in mind that it’s not going to be a single bullet you can use to treat food allergy,” says Supinda Bunyavanich, an allergy expert at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Gut bacteria act in communities, she says, and that the different species may influence how the immune system acts.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter