Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Toxicology

Can Europe replace animal testing of chemicals?

As revisions to the EU’s regulatory system look certain to increase toxicity tests on animals, the region ponders whether it will ever be able to conduct chemical safety assessments with alternative methods

by Vanessa Zainzinger, special to C&EN

August 15, 2022

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 100, Issue 28

Credit: Martin Pope/Getty Images | A demonstration in England on World Day for Laboratory Animals. Despite opposition around the world, animal testing is set to increase in the European Union.

In brief

Before chemicals reach the European market, they must undergo rigorous safety assessments, which often include tests on animals. New data requirements are about to greatly increase animal testing, reigniting a heated debate about whether regulators can do better. But efforts to replace animal tests with alternative methods continue to falter because of a regulatory system that is not built for them. And concerns remain that nonanimal tests would stand in the way of the European Union’s ultimate goal of protecting human health and the environment from hazardous chemicals’ effects.

On Sept. 15, 2021, members of the European Parliament overwhelmingly voted in favor of a European Union–wide plan for phasing out the use of animals in research and testing. The plan demands that the European Commission set “ambitious and achievable” objectives and timelines for transitioning to a research system that does not use animals. Highly publicized at the time, the parliament’s call to action epitomized political and societal pressure to eliminate animal testing in Europe.

With less fanfare, the commission was also beginning last fall to implement a set of policy initiatives that are part of the European Green Deal, a road map for making the EU carbon neutral by 2050. First presented in December 2019, the initiatives require tougher controls on chemicals—controls that are certain to result in substantially more testing on animals than is currently required.

These contradictory actions encapsulate a debate that has vexed the European chemical community for decades. In theory, assessing chemical safety without using animals means everybody wins: it’s cheaper, it’s faster, and it allows regulators to scan more substances for potential hazards without causing unnecessary suffering. But in practice, some experts say, testing without animals can come at the cost of protecting human health.

Now, the prospect of a surge in animal testing has increased the sense of urgency to find a way out of the current testing system. Toxicologists, animal rights campaigners, corporations, and regulators are hotly debating when, if ever, Europe will stop using animals for chemical safety assessments.

Seeking alternatives

The chemical industry and regulators have been throwing their weight behind efforts to develop alternative test methods—commonly referred to as “new approach methodologies,” or NAMs—since the 1980s, says Gavin Maxwell, who leads the Safety and Environmental Assurance Centre at the consumer product giant Unilever, which is against testing its ingredients on animals.

By the early 2000s, alternatives to animal tests for local toxicity, such as skin corrosion and eye irritation, were mature enough to be used for regulatory testing and to justify a series of EU bans on the sale of animal-tested cosmetic products and ingredients. Since then, stakeholders in Europe have invested an estimated $2 billion to develop, evaluate, and apply NAMs to chemical safety assessment, Maxwell says.

“Over the past 2 decades, we’ve witnessed a huge acceleration in our scientific mechanistic understanding of toxicity and ecotoxicity,” he says. “There’s a win-win-win here: we can use NAMs to improve human health and environmental protection and accelerate sustainable chemical innovation. Why should assessing chemical safety still be based on animal tests—some of which date back over 50 years—when we can also apply the latest safety science?”

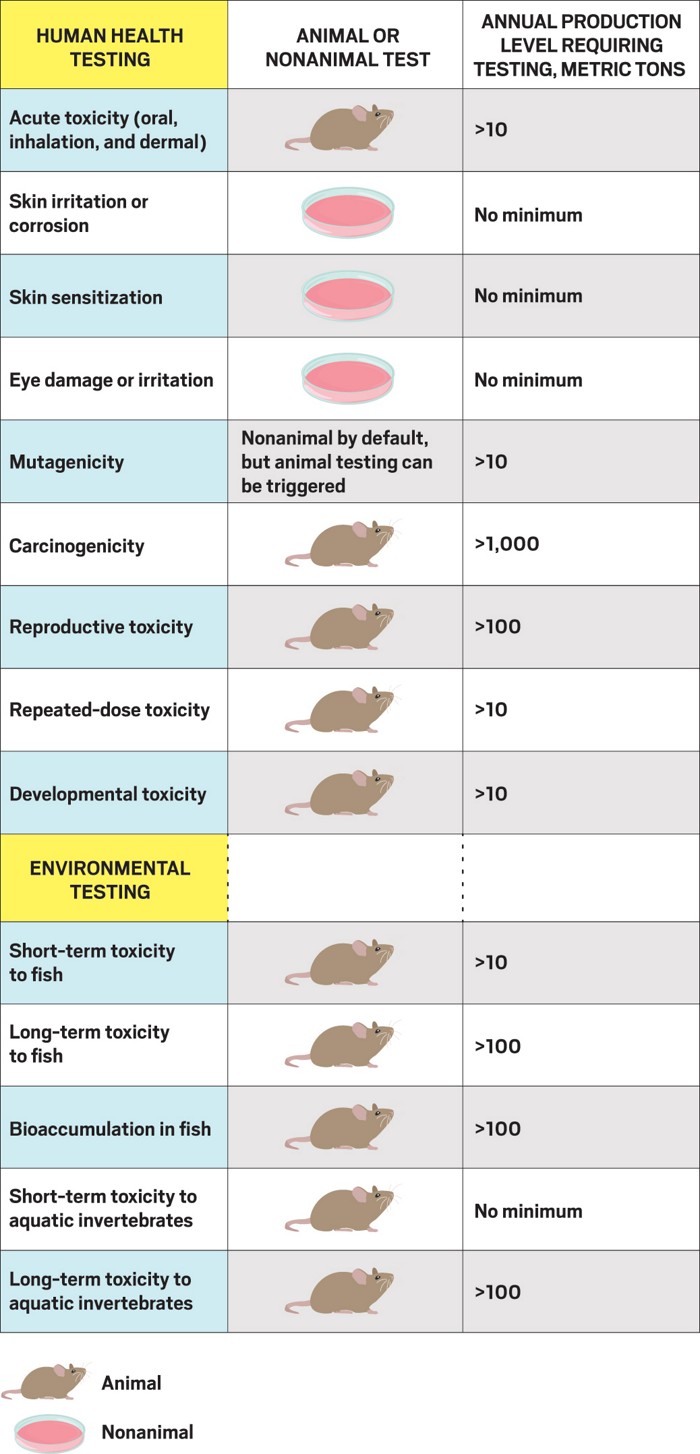

But despite these efforts, EU chemical laws still require animal tests for most health effects. “Currently, NAMs cannot be used for basically anything,” says Christina Rudén, a professor of regulatory ecotoxicology and toxicology at Stockholm University. Regulators allow nonanimal tests to show whether a chemical causes eye and skin irritation or corrosion. “But as far as the complicated end points are concerned—reproductive toxicity, developmental toxicity, carcinogenicity, any long-term chronic toxicity—it’s very, very difficult to assess that with NAMs,” she says.

“It’s not like we haven’t tried,” Rudén says. “The requirement to reduce animal tests has been there for a long, long time. And the attempt to develop new methods and put them to regulatory use has been ongoing for decades, but it has not been proven successful.”

Skeptics say NAMs cannot reliably assess complex health effects in humans—and they may never be able to. Unlike skin and eye irritation, in which the toxicity is limited to the body part that was exposed to the chemical, more complex health effects involve a chemical’s absorption and distribution throughout the body and its organs.

A chemical’s systemic effect on humans is most comparable to its effect on an animal, Rudén says. Nonanimal methods, such as cell cultures, she says, can generate useful information to help researchers understand the effect, but they paint a much smaller picture.

“A mouse is not a perfect model for the human, but it’s much broader than one type of cell. Replacing it with a set of nonanimal methods limits the scope of information that you get,” she says.

Experts are concerned that NAMs will fail to uncover health effects and will let hazardous chemicals slip through the EU’s safety net. “For every little end point or effect that you don’t look at, we reduce the level of safety,” Rudén says.

European regimen

It’s an animal data system

By the numbers

2.6 million

Number of animals that have been used in tests under the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) law since 2007

1.6 million

Number of animals expected to be used in tests for REACH polymer registration

2.0 million

Number of animals expected to be used in tests for REACH testing of lower-tonnage substances

3.6 million– 5.1 million

Number of animals expected to be used in tests for REACH testing of endocrine-disrupting properties

Sources: Cruelty Free Europe, European Chemicals Agency 2020 report.

Others say the problem lies not with NAMs but with the EU’s famously rigid regulatory system. The system is based on two massive, interacting flagship laws: the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) regulation and the Classification, Labelling, and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures (CLP) regulation. In the EU’s extensive legal universe, REACH and the CLP apply to all chemical substances. These laws are orbited by other sector-specific laws imposing additional rules on the chemicals that can be used in particular products, such as cosmetics, toys, and pesticides.

REACH controls the manufacture, import, supply, and safe use of chemical substances in the EU. Companies must register every chemical with the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) by submitting a dossier with hazard information and risk assessment data. The CLP requires companies to classify, label, and package their hazardous chemicals correctly before placing them on the market. And it affects what data companies must generate for other regulations, such as REACH.

The regulatory system was built on the kind of information that scientists get from animal studies, says Ofelia Bercaru, ECHA’s director of prioritization and integration. The system regulates chemicals on the basis of adverse effects observed at a particular dose. These effects may be in the structure, function, growth, development, or life span of an organism.

Nonanimal methods don't offer the same observable effects as animals do, making them poor substitutes in complex studies, Bercaru says. Moreover, some of the effects a chemical can have on humans are still poorly understood, Bercaru says. "For neurotoxicity and immunotoxicity, for example, it’s difficult to develop NAMs if you don’t understand what it is that generates the effect.”

According to REACH, testing on vertebrate animals should be used only as a last resort. But the law, which increases information requirements for a chemical as production volumes increase, generally requires in vivo tests for chemicals produced in volumes of more than 10 metric tons per year. Amendments to REACH in 2016 and 2017 made nonanimal testing the default for skin sensitization, skin corrosion or irritation, and serious eye damage or eye irritation. Testing for most other health effects, however, still requires animals.

To an extent, registrants can sidestep these requirements with strategies such as read across, the practice of using information from similar tested chemicals to deduce the toxicity of an unassessed chemical. Still, animal welfare groups estimate that 2.6 million animals have been used for testing under REACH since the regulation's inception.

Now, to the consternation of such groups, the number of animals used for testing in the EU is due for a steep increase. The European Green Deal included the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS), which promises to toughen the EU’s already-rigorous laws on hazardous substances in everyday products. Under the CSS, REACH and the CLP are being revised to improve chemical safety—and consequently require millions more animals for tests.

The revisions are still under discussion. But they are almost certain to add new information requirements to REACH and hazard classes to the CLP that mean chemicals will for the first time have to be tested for endocrine-disrupting properties, respiratory sensitization, and immunotoxicity—all highly complex determinations for which there are no accepted nonanimal test methods.

The CSS may also require more information for smaller batches of substances and introduce registration requirements for polymers, which will have “horrendous implications,” says Emma Grange, head of science policy and regulation at Cruelty Free International, an animal welfare group. Around 33,000 polymers could require REACH registrations, leading to 1.6 million animals used for testing, the group estimates.

The CSS does include actions that would reduce the number of animals needed for tests. They include assessing chemicals in groups rather than individually and a “one substance, one assessment” framework, which envisions European agencies, such as ECHA, becoming better at sharing information so they don’t have to ask companies for additional data.

Nonetheless, the CSS is moving things in the wrong direction, says Marina Pereira, a senior strategist for regulatory policy at Humane Society International, an animal rights group. “This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity where we are reopening so many of these regulations that will have effects for decades, and whatever is decided now will be locked into this system for years to come,” she says.

“Under the CSS, it is recognized that there is the need to innovate and reduce dependency on animal testing, but when we look at the proposals that are being put forward, what we are seeing is exactly the opposite,” Pereira says. “It’s making what is already a very onerous system of testing even bigger.”

The promise of NAMs

To animal rights campaigners like Pereira, NAMs are an opportunity to improve the EU’s regulatory system in ways that do more than just save animals from suffering.

Good alternative methods can generate vast amounts of data, reduce testing costs, and provide predictions faster than is done today, says Marcel Leist, head of the Department of In Vitro Toxicology and Biomedicine at the University of Konstanz.

Leist, who is also director of the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing in Europe, says NAMs can bring a level of precision to chemical safety assessments that animal studies don’t offer. For instance, they are better than animal tests at helping toxicologists understand the mechanism of toxicity, he says. Animal tests show only whether a substance is toxic; they cannot model intricacies such as human genetic backgrounds.

“There are NAMs where different genotypes or human allelic variants can be used, and the variation of humans can be predicted in a much better way,” Leist says.

Last year, a joint statement by Cruelty Free Europe and the European Chemical Industry Council, an industry association, said animal tests are often unreliable and produce inconclusive results. Cruelty Free Europe backed up this claim with several studies. For instance, an analysis of 1,000 substances tested on animals for developmental toxicity found that results for compounds tested twice in the same species—rats or rabbits—differ up to a factor of 25. Another study found that a mouse test for skin sensitivity correctly predicts allergic reactions in humans only 72–82% of the time.

“It’s been a frustration of my work over many years that animal data is often so irreproducible that it’s difficult to calibrate other methods on them,” Leist says. “What we have learned is that, very often, the limitation for validating alternative methods is the bad quality of the animal experiments.”

Advocates of NAMs say the data they provide is not better or worse than animal test data, only different. “Characterizing and dealing with scientific uncertainty is a fundamental element of chemical safety assessment, irrespective of what methods are used,” says Maurice Whelan, head of the Chemical Safety and Alternative Methods Unit of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre.

Whelan says that when regulators make decisions—such as about a safe level of exposure—they consider sources of uncertainty that affect animal test results. For example, they account for having limited data on a chemical and for extrapolating the results of a rodent test to humans. “Shifting to NAMs doesn’t necessarily mean more uncertainty but simply differences in sources of uncertainty that can be characterized and dealt with, just as we do now with conventional tests,” he says.

Advertisement

But to Whelan, the discussion of NAMs gets sidetracked by its focus on replacing animals. Rather, he says, moving away from animal testing should be just one part of Europe’s main goal under the CSS, which is to better protect human health and the environment via more hazard data on more chemicals.

To that end, Whelan says, regulators can do more to identify where NAMs can offer something new and valuable. “Good examples include the assessment of endocrine disruptors or developmental neurotoxicants, where NAM-derived, human-relevant mechanistic data can be of central importance,” he says.

Regulators’ discussions about NAMs often focus on using them as a way to reduce, not eliminate, animal testing. For example, high-throughput screening tools would allow regulators to pinpoint which chemicals are likely to be hazardous and need additional testing on animals.

This strategy is shunned by animal rights groups, which say it ignores that NAMs are good testing tools on their own. But it is favored by those who believe accepting data from NAMs alone would mean lowering the bar for protecting human health.

“I am skeptical of using only NAMs to prove safety,” says Anna Lennquist, a senior toxicologist with the International Chemical Secretariat (ChemSec), a Sweden-based nonprofit that advocates for stricter controls on potentially harmful chemicals. “I don’t think we are there yet. But NAMs could help us understand which chemicals are probably problematic.”

A system overhaul

For all of the potential of NAMs, the EU’s regulatory system makes adopting them difficult. Before a method can be used for regulatory purposes, it must be validated and entered into official test guidelines by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). EU regulators accept only tests done according to these internationally accepted methods, to ensure companies submit data that are consistent and held to a high standard. But the process for getting new methods approved by the OECD is painfully slow, says Robert Landsiedel, vice president of special toxicology at BASF, Europe’s largest chemical manufacturer.

It took BASF and Givaudan 10 years to receive OECD approval for a multimethod, animal-free testing approach to predict skin sensitization. It was the first overall testing strategy to predict skin allergic reactions without using animals, and its approval in June 2021 was a milestone.

Part of the reason it took so long, Landsiedel says, is an uncoordinated approach to developing new test methods. “We have been developing method by method independently, and then we try to fit them together, which is the most inefficient way to have a complete battery in the end,” he says. Replacing an animal test for complex health effects requires combinations of methods, he says, and toxicologists have begun moving away from trying to replace specific animal tests with a single nonanimal method.

Almost all the recent NAMs adopted by the OECD were developed by companies, not academics. The latter are often too unfamiliar with the intricacies of the regulatory system to design methods that fit in it, Landsiedel says. “Funding programs for lab development of new methods are pretty good, but then the last steps of validation and regulatory acceptance are just neglected,” he says. “So we have good methods but no plan for how to take them further.”

If Europe continues this way, it will not be replacing animal tests anytime soon, Landsiedel says. The standard 90-day toxicity study on animals required under REACH examines effects on 30 organs. Replacing it will require about five NAMs per organ, Landsiedel says, and the OECD is currently adopting three or five methods per year. “If we go on like we do today, it will take 30 years to fully replace animal testing,” he says. “What we can learn from that is we have to do it differently or we wait 30 years. That’s the simple truth.”

What destines Europe for such a long wait is that regulations are based on adverse outcomes, Landsiedel says. NAMs provide different information: “Not better or worse per se, just different,” he says. If Europe were to replace animal testing, “we would regulate based on key events, and almost inevitably a risk-based system. We would not regulate based on adversity.”

Lately, the animal-testing debate has shifted toward asking what it would take for NAMs to thrive in the EU’s legal environment. If Europe wants to eliminate testing on animals, experts say, it needs to find not only new methods but also a new regulatory system.

For now, however, such an overhaul is not likely. Although the European Green Deal revisits REACH and the CLP, it prioritizes environmental and human health, not reducing animal testing. The European Commission, meanwhile, is bound to strict timelines for the revisions, and those don’t allow time to rethink how the system works.

The lack of a discussion about serious change is a source of frustration for animal welfare groups. “We should be having it now,” says Cruelty Free International’s Grange. “If we are going to transition away from animal testing, we need processes built into regulations today, and without those, we will always be in a situation that we can’t change until there is a revolution. We need to allow new methods to come into being.”

Grange would like to see mechanisms built into REACH and the CLP that allow the laws to be regularly updated with new test methods. As Europe covers more types of toxicity under its flagship laws, it needs to improve its use of NAMs more than ever, she says. “Reliance on animal testing was never the right way to go about regulating chemicals, and it shouldn’t be the way to go about it in the future.”

Ultimately, Unilever’s Maxwell says, animal testing will become a last resort if the EU allows new approaches to fulfill REACH and CLP information requirements as soon as those approaches are proven “scientifically relevant.” He is optimistic that Europe can at least significantly reduce animal testing for chemical safety assessment within this decade. “I believe that we’ve been preparing the ground for the last 20 years, and we’re far closer to achieving this goal than we realize,” Maxwell says.

But ECHA’s Bercaru cautions that any breakthrough in understanding how the EU can create a different system will be in the relatively distant future. “We are still far from replacing animal tests completely,” she says. “It’s a slow process.”

Vanessa Zainzinger is a freelance writer who covers the chemical industry.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter