Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Toxicology

US FDA seeks to slash animal testing

Advocacy groups push for nonanimal methods to predict the safety of drugs, including cannabinoids

by Britt E. Erickson

August 2, 2022

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 100, Issue 27

Lawmakers and animal welfare groups are increasing pressure on the US Food and Drug Administration to stop requiring animal tests for all products under its jurisdiction, including new drugs. Animal models have played a critical role in bringing new therapies to market, but testing compounds on animals raises ethical concerns. In addition, animal models don’t always predict toxicity in humans.

Drugs are absorbed, distributed, and metabolized differently in different species. Many drugs fail because toxicity problems do not arise in animal models but appear in human clinical trials. People enrolled in the studies pay the consequences.

The opposite could also be true. Therapies that may benefit people might not make it to market because of toxicity in animal studies, yet that toxicity may be irrelevant to humans.

The FDA is taking seriously requests to reduce animal testing. The agency is seeking advice from its Science Board—a panel of external scientists—on how to qualify nonanimal methods for evaluating the safety of new products.

“While we are nowhere near being able to replace all animal testing, there are opportunities for alternative methods to make additional inroads,” David Strauss, director of the FDA’s Division of Applied Regulatory Science, told the Science Board during a June 14 meeting. Strauss works within the FDA’s drug center, but he was speaking on behalf of a new alternative methods (NAMs) group, which spans all the FDA’s product centers.

The FDA oversees a broad range of products well beyond drugs, including biologics, cosmetics, food, medical devices, and tobacco. Animal testing has traditionally played an important role in establishing the safety and efficacy of all these products, Strauss said.

Strauss coleads the NAMs group, which aims to spur the adoption of nonanimal methods that can replace, reduce, and refine animal testing for regulatory purposes across the agency. The group’s goals are to replace animal testing with alternative tests that are more relevant to humans, reduce the number of animals required for testing, and refine remaining animal test methods to eliminate pain or distress and to enhance animal wellbeing, Strauss said.

In the case of new drugs, the FDA reviews animal data submitted by developers to establish safe dosages and other conditions so therapies can be safely administered to patients, Strauss said. The FDA also relies on animal data to determine whether medical products pose an increased risk of cancer or reproductive and developmental toxicity. That work typically involves histopathological analysis of all major organs, which “cannot ethically be obtained in humans,” Strauss said.

But advances in new technologies, such as microphysiological systems—2D or 3D cellular systems that mimic human organs—combined with in vitro cellular tests and in silico computational models, “present new opportunities to improve our ability to predict risk and efficacy,” Strauss said. These tools may also “help bring products to market faster,” he said.

Many of these tools have “reached some degree of standardization and reliability,” Janet Woodcock, principal deputy commissioner at the FDA, told the Science Board during the June 14 meeting. “Now is the time to start really looking at, Can we qualify them for various uses?” she said. These uses could include toxicology tests used for drug development, she added.

The qualification process “is a way to rigorously determine the performance of a new evaluative method or new tool,” Woodcock said. The FDA looks at what the new tool can do and to what extent the agency can rely on it for making a decision in a specific regulatory context, she added.

The FDA has qualification programs for drugs, biologics, and medical devices, Strauss said. The process has multiple steps and is time consuming, but once the FDA qualifies a tool for a specific use, any developer can use the tool for that purpose without having to validate its performance.

The agency is seeking advice on how to enhance its qualification processes and whether other FDA product areas should have qualification programs. The FDA plans to form a subcommittee of the Science Board to explore the topic.

To date, the FDA has allowed alternatives to animal testing to demonstrate product safety in only a handful of cases. In drug development, the agency has accepted a biomarker that uses human pluripotent stem cells in vitro at the nonclinical stage to detect developmental toxicity, Strauss told the Science Board. In addition, physiochemical and in vitro methods can be used instead of animal studies to evaluate whether a drug can induce a photochemical reaction in tissues, leading to irritation or an allergic reaction. Also, reconstructed human cornea–like epithelium and 3D reconstructed human epidermis models have replaced rabbit tests for eye irritation and skin sensitization, he said.

Next-generation sequencing is a proposed alternative for detecting viral agents in biologics. And efforts are underway to replace animal tests with monoclonal antibodies to quantify key parts of the rabies virus vaccine.

In the food area, in vitro assays for detecting paralytic shellfish toxin are approved by the National Shellfish Sanitation Program, a federal and state cooperative program, as alternatives to an animal test. The National Toxicology Program is also proposing in vitro approaches for detecting the presence and potency of botulinum neurotoxin to replace a mouse assay, Strauss said.

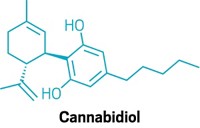

One area that is ripe for new methods is the evaluation of the safety of food ingredients and dietary supplements that have pharmacological activity. In particular, the FDA has been struggling to regulate cannabidiol (CBD), a bioactive cannabinoid extracted from hemp, since the plant was legalized in the US in 2018.

The agency held a public meeting in May 2019 to get input on how to regulate the emerging CBD market. In the meantime, unregulated CBD products of variable quality—including cosmetics, dietary supplements, food and beverages, and pet food—have proliferated. But the FDA has yet to propose any regulations.

CBD is the active ingredient in the drug Epidiolex, which the FDA approved in 2018 to reduce seizures in children with rare epileptic disorders. The drug was in clinical trials before it was marketed as a food or dietary supplement. That timing prohibits CBD from being added to food and excludes it from the definition of a dietary supplement, although the FDA can override the prohibition. “We do have the ability to issue a regulation that would allow the use of a pharmacologically active ingredient—an approved drug, for example, or something that was studied as a drug—in a food or dietary supplement,” Woodcock told the Science Board during an afternoon session devoted to regulating cannabinoids. In addition to being principal deputy commissioner, Woodcock is chair of the FDA’s Cannabis Product Committee.

The FDA has repeatedly raised concerns about liver, immune, developmental, and reproductive toxicity associated with oral CBD exposure. The agency first raised those concerns during its evaluation of mouse studies submitted by GW Pharmaceuticals as part of the drug approval process for Epidiolex.

But humans and mice metabolize CBD differently. It is unclear whether the human metabolite, 7-carboxy CBD, creates the same problems as 7-hydroxy CBD, the metabolite produced by mice.

“We can do a lot of studies in animals that have different metabolites. And if we don’t understand the relative contribution of the different metabolites, those studies could be leading us astray,” Woodcock said. The FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research is conducting studies to determine which animals have similar CBD metabolites to those of humans, she added.

Stakeholders are urging the FDA to consider human-relevant NAMs and human clinical studies to fill in data gaps related to CBD’s toxicity. “This is a great opportunity to leverage NAMs utilizing human cell lines” and human clinical data, “to fill these data gaps in a targeted, pragmatic, and mechanistic way,” Joseph Dever, director of toxicology at NSF International, which certifies that dietary supplements and other products are made under good manufacturing practices, said during public comments at the Science Board meeting.

The FDA is asking Congress for $5 million in new funding to support its NAMs initiative in fiscal 2023, which begins Oct. 1. The program would be coordinated by the FDA’s Office of the Chief Scientist. It is unclear whether lawmakers will give the FDA the money for the proposed NAMs program, but members of Congress in both the House of Representatives and the Senate support the idea.

“I believe that FDA’s qualification programs have the ability to really revolutionize product development. I also think we need a lot of improvement around efficiency and timelines compared to the current programs,” Elizabeth Baker, regulatory policy director at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, said in public comments at the meeting. “Patients are suffering and dying of toxicities while we wait to qualify these new methods that may be able to better detect these toxicities than the animal studies,” she said.

The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine advocates for effective, efficient, and ethical research and testing. The group is disappointed that the FDA also requested $7.5 million for the National Center for Toxicological Research to compare NAMs and animal tests side by side. “It would result in the death of many new animals for NAMs evaluation. So for NAMs intended for testing human products, this is a step back with regard to science and ethics,” Baker said.

Legislation to reauthorize the FDA to collect user fees from product developers is also working its way through Congress. The current authorization expires Sept. 30. Lawmakers reauthorize FDA user fees every 5 years. Such fees, which make up more than 40% of the agency’s total budget, are intended to speed up the review of the safety and efficacy of new prescription drugs, generic drugs, biosimilars, and medical devices.

Both the House and Senate versions of the bill to reauthorize FDA user fees include language that would allow the agency to consider nonanimal methods for preclinical testing of new drugs. The FDA could still require animal testing, but it would not have to.

The House passed its version of the user-fee reauthorization bill, the Food and Drug Amendments of 2022 (H.R. 7667), on June 8. As of C&EN’s deadline, the Senate had yet to vote on its bill (S. 4348), which cleared the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions on June 14.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter