Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Cloudy outlook for sunscreen ingredients in the US

DSM is close to winning US FDA approval for a new UV filter, the first in almost 20 years, just as the agency considers removing most other options from the market

by Craig Bettenhausen

November 27, 2022

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 100, Issue 42

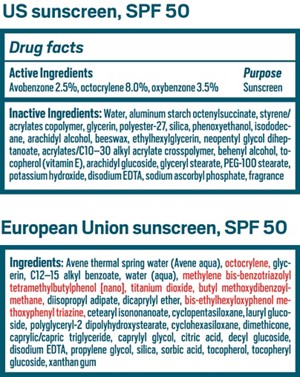

Pasquale Aramo stocks up on sunscreen when he travels outside the US for work. Aramo, vice president of specialty chemicals for the Americas at the personal care ingredient supplier 3V Sigma, is not alone among personal care professionals in doing so. The regulatory structure in the US means that sunscreen makers have fewer choices for the chemicals that filter out ultraviolet (UV) light than they do in most of the rest of the world, and none of the filters developed in the past 2 decades are allowed.

The public health stakes are high. According to minutes from a 2015 meeting between officials at the US Food and Drug Administration and the chemical maker BASF, skin cancer attributable to UV radiation is responsible for 10,000 deaths per year in the US. In addition, skin cancer rates rose 800% for women and 400% for men between 1970 and 2009.

The core of the problem is that the US government considers sunscreens over-the-counter medications, whereas most other regions treat them as personal care products or cosmetics, akin to hand lotion. The FDA, which regulates both categories, subjects new UV filters to the same level of scrutiny as it does a drug. In a regulation proposed in 2021 and in other communications, the agency says it also wants to examine the ingredients already on the market against the same standard.

Drug or cosmetic?

Meeting that standard will mean absorption studies and extensive clinical trials to establish with a high degree of certainty that the ingredients are effective and safe. Sunscreen makers and their chemical suppliers are reluctant to pay for such tests because few of the UV filters they would like to use would qualify for patent protection, and the profit margin on sunscreen is nowhere near what it is on pharmaceuticals.

All that has largely been true for decades. But two things are moving in the glacial world of US sunscreens. The chemical maker DSM is advancing bemotrizinol, often abbreviated BEMT, through the FDA approval process. If the company is successful, bemotrizinol would be the first new UV filter to hit the US market since avobenzone in 1996. At the same time, the FDA is threatening to pull approval for existing UV filters because of agency research showing that, other than zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, these compounds absorb into the bloodstream.

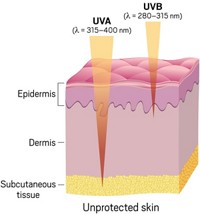

UV filter ingredients are divided into two basic categories, inorganic and organic, also known as mineral and chemical. The inorganic options, ZnO and TiO2, are effective at blocking UV rays—both the UVB wavelength range (280–315 nm), which is the focus of sun protection factor (SPF) ratings, and the UVA (315–400 nm), which is actually a bigger factor in skin cancer.

But inorganics can be hard to make into a lotion that feels good, spreads easily, and stays in place, according to Kelly Dobos, a freelance formulation chemist. ZnO and TiO2 are also white pigments that can give users a pale, ashy, or even painted appearance—a problem that is pronounced for people with darker skin tones.

The organic UV filters are an array of small molecules: 14 in the US and 30 or more in the rest of the world. Their chemical and physical properties, as well as their variety, make them easier to formulate into a consumer product.

“The consumer experience for the most effective SPF products available in the US, which are rich in inorganic UV filters, is not as pleasant as the most protective formulations available in Europe,” Aramo says.

“As an Italian living in the US for almost 7 years,” he adds, “I feel I have limited choices on how to effectively protect myself and my loved ones against the damages related to sun exposure, versus when I was living in Europe.”

The FDA status that makers of sunscreen UV filters seek is known as generally recognized as safe and effective, which is abbreviated GRASE but usually pronounced “grass.” To make a GRASE determination, the FDA looks at how readily a substance absorbs through the skin into the bloodstream, how long it stays in circulation, and how toxic or benign it is to humans.

It sounds simple enough, but the battery of tests the FDA is asking for takes years and costs a lot of money. In the case of bemotrizinol, the final bill will come to $12 million–$20 million, according to Carl D’Ruiz, who leads North American personal care regulatory affairs for DSM. He should know: he’s been trying to get bemotrizinol through the FDA’s red tape for 21 years.

Bemotrizinol’s journey has had many twists and turns. Discovered in the 1990s, the UV filter has been available in the European Union since 2000. D’Ruiz brought it before the FDA in 2002 on behalf of Ciba Specialty Chemicals. BASF bought Ciba in 2009, and D’Ruiz continued dealing with the agency on behalf of his new company.

BASF was pursuing FDA approval of bemotrizinol as well as another filter, bisoctrizole, as recently as 2017 but has since abandoned the effort, according to industry insiders. BASF declined to comment for this article other than to sing the praises of improved forms of ZnO that are more transparent to visible light and are easier to formulate than traditional forms.

D’Ruiz joined DSM in 2018 and a year later told regulators that the firm was picking up as an interested party for bemotrizinol where BASF had left off. He says DSM is finishing the last set of clinical trials and other tests and will submit all the required data to the FDA by mid-2023. The company’s costs will be $5 million–$6 million—on top of the expenses previously incurred by Ciba and BASF, D’Ruiz says. He expects a final GRASE determination for bemotrizinol by mid-2024.

Seven other organic UV filters, all of which are in regular use in the rest of the world, are stuck in the FDA’s approval pipeline. Congress has repeatedly tried to force the agency to move faster, including with legislation in 2014 that attempted to streamline the process; it also ordered the agency to decide on all existing applications within a year. A provision in the 2020 pandemic relief bill tried to remove some regulatory requirements and place protections on the organic filters currently on the market.

Missed deadlines and procedural moves by the agency have mostly maintained the status quo, however, and no new UV filters have received a clear yes or no. The FDA declined to comment for this article.

Many in the personal care world question if the FDA is taking the right approach. In the 2015 meeting, according to records published by the agency, BASF suggested that the FDA adopt a “weight of evidence” approach to sunscreen safety, more in line with EU regulators. The FDA firmly rebuffed the idea, as it has in other forums, saying that a full suite of absorption and toxicology studies, including human and animal trials, is needed to ensure that the ingredients are safe.

Dobos, the personal care formulator, says the FDA may be trying to do the right thing but isn’t striking the right balance between product safety and public health.

“The goal of their organization is to protect consumer safety, so they are being extremely cautious on this. That aligns with their mission,” Dobos says. But, she adds, “we have these new ingredients that have been designed to improve on the limitations of older ingredients.” Those limitations include poor coverage across the UV spectrum, high skin absorption, poor photostability, and irksome formulation properties.

“It seems like a bit of a loss for us in the United States in terms of efficacy, safety, and even just the aesthetics of the products in the way they feel on the skin, which frankly is one of the major reasons people tend to say they don’t use sunscreen often enough,” Dobos says.

Given longstanding use in other parts of the world and the reams of data available, at least bemotrizinol should be available to US customers, D’Ruiz says. “There’s no other sunscreen on the planet that has been tested as much as this one ingredient,” he says. “It’s the same data package as you would have for a new drug application. None of the existing sunscreens have this data.”

Why is one molecule worth so much bother? Bemotrizinol’s best quality is its size. At a molecular mass of 628 Da, it doesn’t absorb through the skin or penetrate cells well. D’Ruiz says existing toxicology results look great, and the absorption studies show little or none of the UV filter reaches the bloodstream. Overall, the testing indicates that BEMT is safe even at very high use levels—results that should support a GRASE status for the ingredient, he says. On top of that, bemotrizinol absorbs a wide band of UV light in both the UVA and UVB ranges.

With exposure to the UVB portion of the spectrum, “you get that direct change in skin tone hours later or the next morning,” says David Andrews, a senior scientist at the nonprofit Environmental Working Group (EWG). Current SPF ratings measure only UVB protection. UVA rays have more delayed and insidious risks, including cancer and other detrimental health effects, Andrews says.

Research on melanoma and other conditions suggests that the ratio of UVA to UVB reaching the skin may also affect cancer rates. Broad-spectrum coverage is by far the safest bet, Andrews says.

Given its broad UV efficacy and solubility properties that make it easy to formulate, bemotrizinol is an ingredient of choice, D’Ruiz says. To do something meaningful about skin cancer, he says, DSM is willing to invest the time, money, and effort even if competition from other bemotrizinol suppliers starts on day one.

For many chemical firms, though, a sunscreen molecule isn’t worth the hassle and expense of a pharmaceutical-grade battery of tests and clinical trials. UV filters don’t command drug-level pricing, and most of the molecules are off patent.

“This is the essence of the problem,” Aramo says. Pharmaceutical firms have patents, trade secrets, and other mechanisms to secure high profit margins on new medications, he says. “For all of the UV filter active ingredients, we are talking about commodities at a maturity in their life cycle that cannot guarantee a return on that investment.”

Just as bemotrizinol seems likely to join the sunscreen formulator’s toolbox in the US, the FDA is firing warning shots about the organic UV filters on the market now. Regulators say they don’t have the data they need to decide if any those filters are GRASE.

Agency scientists recently published a study showing that under normal usage conditions, most commonly used organic UV filters show up in the bloodstream at levels that trigger a toxicology study requirement (AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, DOI: 10.1208/s12249-022-02275-z). That’s as far as the FDA will go with internal research, though. The agency says it’s up to industry to generate the rest of the data needed for GRASE determination; it will review the industry’s progress annually and rescind approval for ingredients that no one is pursuing.

The FDA’s analysis in the proposed 2021 regulations hints at its thinking for some ingredients. Zinc oxide and titanium dioxide will almost certainly remain on the market with GRASE status. Aminobenzoic acid—better known as PABA—and trolamine salicylate will be pulled from the market, though the industry has already largely abandoned the two ingredients.

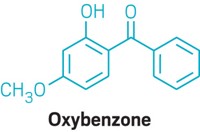

The data are also damning for oxybenzone. The FDA’s analysis expresses concern that the molecule is a threat to human reproductive and endocrine systems, as well being a possible allergen. And FDA-generated research shows that the molecule rapidly absorbs through the skin and remains in the bloodstream for weeks.

Advertisement

Avobenzone, the 1996 addition to the US filter roster, is looking good. Although it also entered the bloodstream in the FDA’s published studies, data in the public record and submitted to the FDA by the personal care maker L’Oréal suggest that avobenzone has a “favorable safety profile.” EWG recommends that consumers look for sunscreens based on avobenzone, and D’Ruiz sent the FDA a 27-page letter in 2019 making a case for avobenzone as GRASE.

Avobenzone is a good UV filter that formulates well, Dobos says, and the only one currently on the US market with both UVA and UVB coverage. But, paradoxically, it isn’t very photostable, she says, so it needs other ingredients to support it in sunlight for it to provide long-lasting protection.

The FDA says it can’t make a GRASE determination for the rest of the 14 organic filters—cinoxate, dioxybenzone, ensulizole, homosalate, meradimate, octinoxate, octisalate, octocrylene, padimate O, and sulisobenzone—because the record contains significant gaps.

EWG goes a step further than the agency, writing in a November 2021 comment to the FDA that there’s more than enough evidence to yank approval for both oxybenzone and homosalate, a suspected endocrine disruptor. “Currently, sufficient scientific data indicates that these compounds are not generally recognized as safe for their intended use,” the comment says.

“There is a public interest to ensure the safety of these ingredients that are being applied to a large part of the body, oftentimes daily,” Andrews says. And FDA testing has shown that all existing UV filters are absorbed into the blood and distributed throughout the body, even from a single application, he says.

Overall, the US outlook for UV sunscreen filters is cloudy, and a few years from now the palette of chemicals that formulators like Dobos have to work with may look very different.

D’Ruiz is optimistic that DSM will get bemotrizinol through the FDA and that other ingredients will follow, with the testing perhaps paid for by industry consortia instead of one or two companies. “The lack of innovation in the United States for almost 20 years is really not acceptable,” he says. “These modern UV filters have been used globally by billions of people, and I don’t see any significant adverse events occurring or being reported where people are dying because they’re using sunscreen. Rather, they’re not dying because they are using sunscreen.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter