Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

How companies are getting 1,4-dioxane out of home and personal care products

Chemical makers, cleaning product firms, and cosmetics makers are all scrambling to meet new limits on the impurity

by Craig A. Bettenhausen

March 22, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 11

When it comes to cleaning, ethoxylated fatty alcohols are the good stuff, beating conventional soap in cleaning power while being gentle on skin and clothes.

They and their foamy, sulfated cousins are the chemical backbone of the cleaning and personal care industries. These biodegradable workhorse surfactants have polar heads and long, nonpolar tails. As is the case with soap, this structural motif lets them play the intermediary between greasy substances and watery ones, binding emulsions together in a lipstick or helping a dish detergent wash away butter.

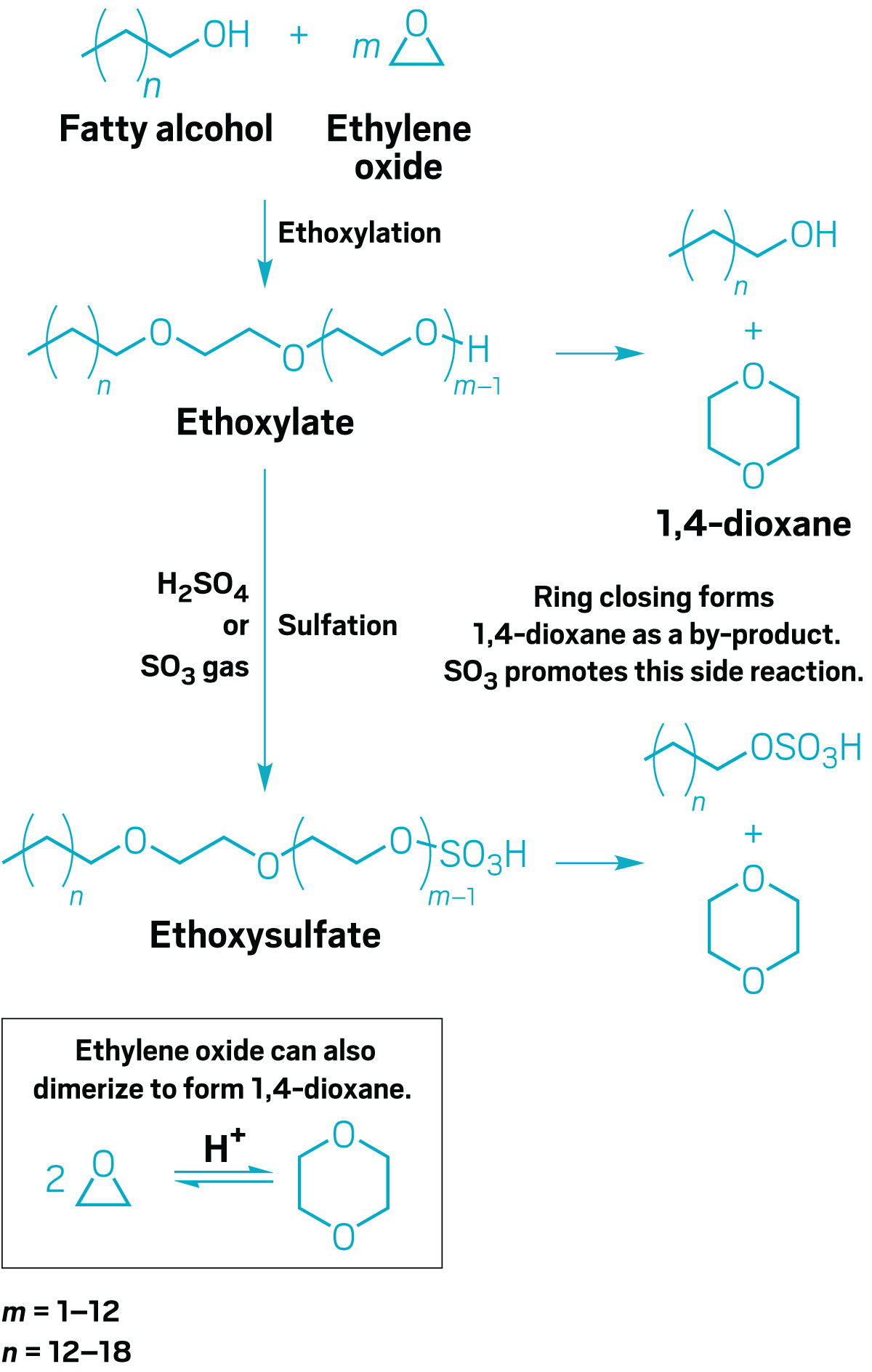

But the ethoxylation and sulfation steps involved in producing these surfactants can create 1,4-dioxane as a by-product. The US Environmental Protection Agency calls dioxane “a likely human carcinogen” that “does not readily biodegrade in the environment.” Growing worries about dioxane are forcing cleaning product makers—and the chemical companies that supply them—to adapt.

Citing concerns about groundwater contamination, New York State passed a law late last year severely limiting the concentration of dioxane in home and personal care products as well as cosmetics. The hope is that limiting what goes down the drain will limit what comes back up in drinking water. Manufacturers that want to sell in New York must now either reformulate their products with different, dioxane-free surfactants or pay extra for reduced-dioxane versions of the surfactants they’re used to.

The new law, S4389B, calls for no more than 10 ppm of 1,4-dioxane in cosmetics and no more than 2 ppm in personal care and cleaning products starting Dec. 31, 2022. The limit for personal care and cleaning products drops further, to 1 ppm, at the end of 2023.

Cosmetics use ethoxylated emollients, surfactants, and preservatives, but at low enough concentrations that they don’t generally approach the limits being considered, explains Ethan Alden-Danforth, vice president for R&D at the cosmetics manufacturer Autumn Harp. Rinse-off cleansers and shampoos, home cleaning and laundry products, and industrial cleaning solutions are a bigger problem.

“It’s going to be the situations where you’re using SLES [sodium laureth sulfate], polysorbates, or other surfactants with ethoxylation at 20%, 30%, 40% in your formula to achieve your performance goals and aesthetic goals,” he says. “Those are going to be the ones where you’re going to have to go back and reformulate with a different ingredient, or you have to work with the raw material supplier on their trace impurities.”

Most industry insiders expect regulations like this to spread nationwide. “New York is the tipping point,” says Victoria Meyer, who was a surfactants executive at Shell Chemicals and Clariant and is now president of the consulting firm Progressio. “Much like when REACH was implemented in Europe, you know it’s not going to be isolated; it’s going to have wider impacts.”

Indeed, California is considering similar regulations now, having long listed 1,4-dioxane as a cancer risk under the state’s Proposition 65. Environmental advocates in North Carolina, where some of the highest concentrations in groundwater have been found, are also pushing for action. The EPA is evaluating dioxane under the Toxic Substances Control Act, though it is focused mostly on direct industrial production of the chemical as opposed to its appearance as an unintended by-product in consumer products.

And other nations may follow suit. “We have not heard anything from other countries,” says Alberto Slikta, chief operating officer in the US for the Brazilian ethoxylate maker Oxiteno. But “the world listens when something happens in the US.”

It’s not just regulators taking notice. “Independent of what laws are put into place, a consumer perception is being created,” says Daniele Piergentili, vice president for home and personal care for North America at BASF, a major supplier of ethoxylated and ethoxysulfated surfactants. “Low content of 1,4-dioxane in personal care and home care products is preferable to consumers.”

Nobody is putting dioxane into consumer products on purpose. To understand why it’s present, you have to look at how ethoxylated and ethoxysulfated fatty alcohols are manufactured.

The process starts with an alcohol sporting a hydrocarbon chain, usually around 12 carbons long. Ethylene oxide is reacted with the alcohol, adding a C2H4O group to the end, which increases the molecule’s solubility in water. More ethylene oxide can add to the new terminal oxygen, a cycle that repeats 1–12 times in most common ethoxylates.

“You get your best cleaning right on the edge of water solubility at the temperature you’re working at,” says Dave McCall, a detergent chemist at the industrial cleaning product maker Ipax Atlantic-Michigan.

But sometimes, instead of taking on another C2H4O unit, the end of the ethoxy chain closes into a ring and pops off as 1,4-dioxane.

Newer ethoxylation plants have less of an issue. Slikta says the facility that Oxiteno opened in Pasadena, Texas, last year was designed for higher purity and yields ethoxylates below 1 ppm in dioxane.

Sulfation, the addition of SO3 to the end of the ethoxy chain, confers additional properties to the surfactant, such as foaming action and increased cold-water solubility. But excess SO3 can insert itself in the middle of an ethoxy chain instead of adding to the end, and that kicks off more dioxane. In fact, ethoxysulfates have a much bigger dioxane problem than nonsulfated ethoxylates do.

Manufacturers can suppress dioxane formation by carefully controlling reaction conditions such as temperature, residence time, and stoichiometric ratio. A 1997 paper by Norman Foster of the chemical engineering firm Chemithon describes how in one system, a 1:1 molar ratio of SO3 to ethoxylated alcohol produced dioxane at roughly 25 ppm. But at 1:1.06, the product had 500 ppm of the by-product.

Alternatively, chemical companies selling ethoxysulfates can strip dioxane out of their products after sulfation. Chemithon sells a stripping system based on steam; other systems purge the products with nitrogen gas. And plant equipment companies offer production lines that both suppress formation and strip out what does form. The engineering firm Desmet Ballestra says its combined system can produce ethoxysulfates with dioxane concentrations lower than 5 ppm, within the range needed for a final product that complies with the coming regulations.

“It’s about reducing the amount of 1,4-dioxane that is formed,” BASF’s Piergentili says. “And then whatever is formed, you have to have the capability to remove it.” BASF has upgraded its facilities in the US where needed on both fronts, he says.

Though none of the firms selling ethoxysulfates will share the details of their manufacturing methods, most sources say it is easier to suppress dioxane formation than it is to remove the by-product afterward.

Pilot Chemical is a major supplier of ethoxysulfates, including SLES, to consumer brands in the US. Shoaib Arif, a research chemist at the firm, says Pilot’s customers are leaning toward low-dioxane versions of conventional surfactants. Still, he is working with some that are opting to switch to surfactants, such as α-olefin sulfonates, that are made without ethylene oxide and thus don’t form dioxane.

In January, BASF rolled out a suite of products to help affected customers comply with the New York regulations. The Flex line includes conventional ethoxylated and ethoxysulfated ingredients made low in dioxane, replacement ingredients not expected to contain any dioxane, and efficiency and performance boosters that can make up for a lower concentration or absence of ethoxysulfates.

For example, SLES is often present in home and personal care products in high percentages because it’s cheap and effective. But because it can contain up to 300 ppm of dioxane, users can’t always get down to the required levels by suppression or stripping. To address this problem, BASF has a polymer-based booster that can reduce the amount of SLES needed, Piergentili says.

Concentrated laundry detergents such as laundry pods are another prime target for dioxane reduction. The lower water content in concentrates reduces packaging and shipping costs. But even though the final dioxane levels in the wash water are the same as with conventional detergents, the regulations affect the products as they’re sold, and more surfactant per unit volume means more dioxane per unit volume.

Boosters can also make up some of the difference in performance between conventional surfactants and their dioxane-free replacements. Huntsman, for example, offers Empicol XCT 14, a blend of surfactants made without ethylene oxide or sulfates. In the product’s brochure, the company gives an example shampoo formulation with two zwitterionic boosters. One increases viscosity and stabilizes foam; the other makes the blend milder and more tolerant of hard water.

As surfactant makers roll out new ingredients for consumer products, they are also preparing for the possibility that the regulations might expand in scope. “We believe this legislation not only will spread to other states, but there is a very good chance it will become broader,” Oxiteno’s Slikta says. “It’s possible that we will see other market segments being put under maximum 1,4-dioxane levels,” such as agriculture, oil and gas, and industrial and institutional (I&I) cleaners.

The I&I segment would be especially hard hit. Ryan Cotroneo is the chief technology officer at UNX Industries, a formulator and equipment supplier serving that industry. Cotroneo says 90–95% of the products UNX sells would be affected by the concerns about 1,4-dioxane. “Regulations in the household space typically translate into the commercial space within 2–5 years,” he says.

Low-dioxane versions of conventional surfactants would let firms like UNX avoid the cost of reformulation, Cotroneo says, but he’s bracing for them to be sold at prices up to 30% higher.

And many I&I products are highly concentrated, so just like with laundry pods, complying with the new standards will be hard. “We need help reformulating,” Cotroneo says. UNX has its scientific staff visit and even embed in labs where alternative surfactants are being developed. Cotroneo says his firm wants to be the first I&I formulator to offer alternatives as they emerge.

Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) signed the New York law on Dec. 9, 2019, and cleaning product makers are already on the move. “You’ve got 2 years to do it. That’s fairly standard and reasonable,” Alden-Danforth says of the law. “And honestly, there’s a decent number of options, but it’s going to be expensive. Depending on the degree of change, you have to redo a lot of safety and efficacy testing. Those can be expensive.”

Smaller firms might not have the funds or person power to keep up, Cotroneo warns. “Dioxane, in my opinion, is kind of the start of this for the cleaning industry,” he says. “There’s going to be more.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter