Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

What’s that Stuff

What’s ski wax, and how does it help us schuss down the slopes?

Although formulations are kept secret among competing athletes, one thing is clear: Fluorinated ingredients are contaminating ski slopes

by Laura Howes

February 3, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 5

In 2014, Norway was in an uproar. At the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, the country’s dominant cross-country ski team wasn’t getting the expected results. Smørebom, which loosely translates to “waxing failure,” got the blame, along with technicians from Norway charged with prepping the skis. At the professional level, where races can be won by fractions of a second, ski wax choice plays a big role. Because of this, it is a closely guarded secret that stays on the slopes.

When applied to the bottoms of skis and snowboards, ski wax can help athletes and amateurs alike glide through sticky spring snow or schuss down icy slopes, depending on the formulation. Even though some mystery swirls around exactly what’s in professionals’ ski wax, what’s clear is that for about 30 years, some waxes have contained per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Although these substances are prized for their lubricant and water-repellent properties, they’re also known as hazardous chemicals that accumulate in the environment.

In fact, recent studies have shown that PFAS contaminate the environment around ski resorts and the blood of ski technicians who often work there (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b02533; 2010, DOI: 10.1021/es9034733; 2010, DOI: 10.1021/es102033k). So regulatory bodies such as the International Ski Federation are beginning to ban PFAS-containing ski waxes, kicking into gear a hunt for high-performance alternatives.

Back when skis were made of wood and worn not for competition but to get around in the cold snowy conditions of Scandinavia, skiers simply used animal fat or pine pitch and rosin to waterproof their wooden skis. By happy coincidence, sealing the wood against water also created a smooth, hydrophobic surface that helped the skis glide across the snow. Today, from quick downhill races to cross-country treks and everything in between, skis and snowboards are coated in waxes to purposely reduce friction with the snow and make the ride faster. These waxes also now encapsulate a lot more science in their designs.

If you’ve ever stood in front of a rack of ski wax in a shop, the choices can be a little overwhelming. Shelves are lined with various blends, some suited for this temperature or that and some suited to different sports. According to the NPD Group, a retail-tracking service, the wax category of the market for US snow sports equipment boasted sales of $7.5 million during the 2018–19 ski season.

Most modern ski waxes are based on hydrocarbons. Users apply them to the bases of skis or snowboards, scrape off the excess, and then use a brush to give a smooth, hydrophobic surface. The wax protects skis from scratches in addition to giving them their glide. In warm weather, soft waxes based on petroleum wax repel slushy snow and keep skis gliding. On cold, hard snow, long-chain or branched alkanes protect the base of the ski, keeping it smooth and slick. Today’s waxes also contain pigments to help you tell the difference: red for warm snow and blue for cold.

For most skiers, the basic components are enough. But at the competitive level of world cup racing, where the margin between a good race and a win can be tiny, technicians have tinkered with ski waxes for years, adding materials such as graphite or metal powders to deliver any competitive edge they can. Many secret formulas remain just that, secret, but two big advances in ski wax chemistry are well known in the industry. They both made ski waxes even more hydrophobic to stop slush and water from adding drag to skis. The first of those was the addition of the surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate in the 1970s by University of California, Davis, chemist and ski enthusiast Timothy C. Donnelly. The surfactant disrupts hydrogen bonding in the water on the underside of the ski, reducing the friction that this bonding can cause between ski and snow. The second, more problematically, was the addition of PFAS in the 1980s.

The fluorine atoms on the alkyl chains of PFAS make ski waxes good at repelling water, which means even faster gliding. This is great for skiers, especially in very wet and slushy conditions, but not so great for the environment.

During her PhD studies at Stockholm University, Merle M. Plassmann examined fluorinated compounds in ski wax and their presence in the environment (Chemosphere 2013, DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.066). She found numerous fluorinated compounds with carbon chain lengths between C6 and C22 in ski waxes and also in the snow and soil of a ski area in Sweden. It is the longer chain fluorinated compounds that are of most concern because of their status as forever chemicals that resist breaking down in the environment. Some of those are added by the wax manufacturers, but others are impurities from the manufacturing process.

One of the compounds Plassmann found in ski wax and soil samples, perfluorooctanoic acid, will be banned in all products sold in Europe in 2020, including ski waxes. Several other long-chain PFAS molecules found in ski waxes are also under scrutiny from regulatory bodies such as the European Chemicals Agency and the US Environmental Protection Agency, but ski teams still use fluorinated waxes.

In 2019, Plassmann and her colleague Ian T. Cousins were asked by the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet to test ski waxes that it supplied. According to Cousins, the pair used ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry and found that most of the waxes tested still contained long-chain fluorocarbons that have been highlighted as problematic substances.

But manufacturers are now offering fluorine-free waxes and formulations with shorter-chain fluorocarbons that are considered safer. Organizations like the International Ski Federation and the Norwegian Ski Federation are taking matters into their own hands by announcing bans or restrictions on using PFAS-containing ski waxes during competitions, something Cousins welcomes.

“In my view, there are degradable, nonfluorinated alternatives that perform perfectly adequately,” Cousins says, pointing to the hydrocarbon-based waxes that existed pre-PFAS. “Of course competitive skiers would ski slightly slower,” he adds, “but if there was a universal ban, it would be a level playing field.”

But if a ban does mean a slowdown for elite skiers, ski wax manufacturers will keep working to make up that difference. Ski wax company Swix, for example, has been developing new fluorine-free waxes and recently announced it will be working closely with the Norwegian Ski Federation through the next Olympic Winter Games to determine how best to use fluorine-free products.

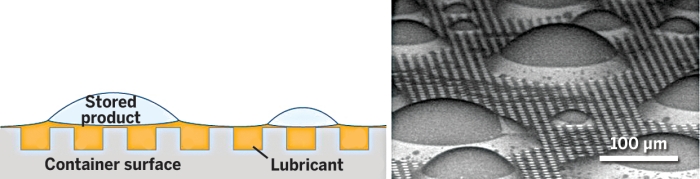

And according to Matthias Scherge at the MicroTribology Center at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, ski wax formulations are only one side of the skiing coin. The other is the base of the ski. If nanostructures could be engineered into that surface to make the ski base more hydrophobic, ski waxes might not need PFAS anymore.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter