Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Instrumentation

Scientific instrument makers weigh the lure of outside money

When it comes to raising funds for growth, small instrument companies look to private equity firms, but sometimes reluctantly

by Marc S. Reisch

September 16, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 36

Small makers of cutting-edge scientific instruments often enable important research advances. But before such firms can help scientists with their discoveries, they need to refine, build, and distribute their tools.

That takes money, and money always comes at a price. Start-ups and even more mature firms that successfully attract outside funds can take advantage of an investment firm’s business connections and make lots of money for everyone. But the loss of control that comes along with that money is not for everyone.

Just as in higher-profile spheres like biotech or software, the investment opportunities in instrumentation fall into three main categories.

Venture capitalists, those that invest in brand-new companies, expect what an entrepreneur would consider very high returns on their successful investments, explains Bruce Belliveau, a principal at Roman Arch Clean Energy Finance. They need big returns on their hits to make up for the many that go south for a variety of reasons, including difficulty in translating technology from lab to commercial product, failed business plans, and poor management.

Midstage investors, generally called private equity firms, have more “modest” expectations, says Belliveau, a chemical engineer who once worked for Dow. They expect about 30–35% returns on investments in firms that are close to proving their value.

And investors in late-stage start-ups, also private equity firms, often look for 20% returns, Belliveau says. These investors inject their cash when firms are starting to sell their wares.

Though Belliveau mostly works in the renewable energy sector, he is an informal adviser to Sean Race, who heads Xigo Nanotools, a 15-year-old company that makes nuclear magnetic resonance–based nanoparticle measurement devices. Xigo’s instruments assess critical particle attributes useful for drug, battery, and electronics developments.

“We’re profitable but small,” Race says. Xigo is about to merge with another company he is not ready to name in a transaction that will add “bulk and diversity to our product portfolio.” Race says Belliveau’s role is to “critique” and make recommendations on Xigo’s business strategy, but Race has mixed feelings about attracting a private equity investor.

Belliveau says well-connected private equity investors can offer “good, high-level guidance on governance and acquisitions.” They can also provide introductions to potential customers and help an instrument maker fine-tune its strategy.

Race isn’t so sure. “I’ve seen more than one instance in which a company languishes after a private equity investment,” he says. But he also acknowledges that the right investor might bring both capital and advice that will allow “everyone to make outstanding returns.”

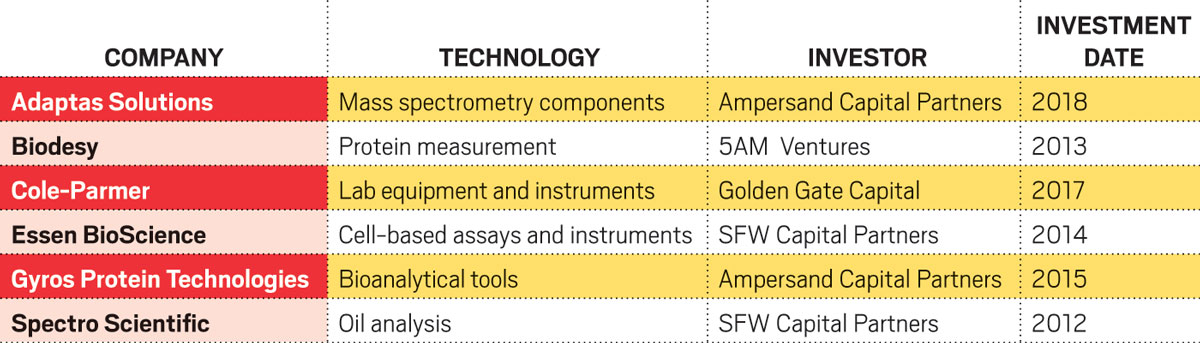

The universe of private equity firms willing to make multimillion-dollar investments in scientific instrument makers is not large. Among them are SFW Capital Partners and Ampersand Capital Partners.

SFW, for instance, has a long and storied relationship with the scientific instrument industry. Just after the liquid chromatography specialist Waters Corporation spun off from Millipore in 1994 and before it went public in 1995, the firm received a significant investment from investors who went on to form SFW.

Earlier this year, Terrence Kelly, the former president of TA Instruments—the thermal analysis instrument division of Waters—joined SFW as an operating partner. He tells C&EN that he will be looking to invest in small, entrepreneurial instrument firms with $10 million–$200 million in annual revenue “and a lot of potential.” Funding for Kelly’s effort will come from a $350 million pool that SFW raised from investors including foundations, endowments, and family-operated investment offices.

Andrew Cialino, SFW’s head of business development, says SFW “has evaluated hundreds of businesses in the instrumentation sector” as it looks for investment opportunities. SFW brings both money and industry knowledge from operating partners such as Kelly who can help small firms build service and marketing organizations that will “take them to the next level,” Cialino says.

SFW can point to a good track record in the instrumentation field. For instance, in 2011, the firm bought the oil analysis firm Spectro Scientific for what industry sources said was $20 million. It bolstered Spectro operations with four acquisitions and then sold the firm in 2018 to the diversified manufacturer Ametek for $190 million.

Kelly hopes to do much the same. In time, he expects he will be able to build an instrumentation business that would complement and extend the business of a larger instrumentation firm.

Cialino admits that larger firms could buy the smaller companies that SFW targets, but he argues that a smaller company’s owners can benefit significantly from a private equity firm’s resources and experiences. Big organizations often don’t focus on or make the R&D investments needed to grow small divisions, Kelly says. “Smaller product lines tend to get lost or disappear inside a larger organization,” he adds.

At the benchtop mass spectrometer maker Advion, CEO David B. Patteson says he is convinced that private equity firms can help smaller companies develop and realize greater value for their businesses. As an operating partner at Ampersand, he is also a little biased.

Partners for profit

Patteson got to know private equity firms when they invested in Advion. In 2011, Advion sold its contract drug research business to the research services firm Quintiles, and private equity firms remained investors. When Advion’s board decided to sell the rest of Advion, it encouraged him to discuss the sale with the private equity firms.

Advion ultimately sold itself in 2015 to the Chinese diagnostics firm Beijing Bohui Innovation Biotechnology, and Patteson subsequently joined Ampersand, one of the private equity firms with which he developed a good relationship. He continues to lead Advion with Bohui’s blessing. Both are potential investors in small instrumentation firms, and he shares his insights on opportunities with both, he says.

When scouting out opportunities for Ampersand, Patteson says, he generally looks for companies that have more than $10 million in annual revenues and are consistently profitable. “Private equity likes to get in where something is working well and kick it into overdrive,” he says. That may be when a firm needs cash to build new facilities, expand its global reach, or acquire another company, he notes.

Ampersand prefers to keep a company’s founder and management on when it make an investment, Patteson says. It also makes sure those executives continue to hold equity in the company so that everyone benefits when the business is ultimately sold.

Patteson acknowledges that some management teams think private investors are “reptiles” who micromanage, have a quick sale in mind, or want to “ace out” management. “That’s something we don’t do,” he says. Sometimes discussions go on for years “before the stars align” for both management and Ampersand, he adds.

Private equity money comes with too many drawbacks, counters Roshan Shetty, the founder of two instrumentation companies. Private investors “often want majority control. And if you don’t meet revenue goals, you’re fired.” Shetty has had discussions with private investors but says “it’s not a fun process.”

He grudgingly acknowledges that taking private equity funding can sometimes make sense. “It’s attractive when you need money to gain traction in the market,” he says. It is also helpful when “you are looking toward retirement and need to raise money.”

Shetty’s first firm, Anasys Instruments, developed the nanoIR, which uses an atomic-force microscope’s resonant response to infrared light pulses for nanoscale measurements. The firm developed the tool and sold Anasys to the scientific instrument maker Bruker last year with “no private equity intervention,” Shetty says.

The early days at Anasys were a struggle, he acknowledges. In addition to government funding, Shetty and his partners dipped into their own savings to keep the firm going. He says he doubts that private equity would have had the patience to wait the 8 years or so it took Anasys to pull off the sale to Bruker. But, he says, the payoff put him in a position to self-fund his new company, Photothermal Spectroscopy.

At Photothermal, Shetty and his partners are developing a microscope equipped with a visible-light probe to get chemical-specific spectra at submicrometer levels. The new firm employs 20 people and has sales of less than $5 million a year. For now he is focused on growing that business.

Shetty says he realizes he is taking a risk with Photothermal and that others might be unwilling or unable to “bootstrap” their new business as he and his partners have. “I have a high risk tolerance,” he acknowledges.

Shetty would argue that it takes a rugged individualist to develop a new instrument and start a company. But, as Ampersand’s Patteson points out, the experience and market knowledge that good private equity investors bring can build “a bridge to a bigger company and a bigger sale.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter