Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Outsourcing

Contract research organizations profit from nonprofits’ drug-discovery efforts

Although the financial returns are not always high, CROs find value in working with foundations

by Vanessa Zainzinger, special to C&EN

August 4, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 31

Like all investors, disease-focused foundations are looking for the best return for their dollars. Unlike other investors, they measure returns not in terms of financial gain but in new drugs that benefit their constituents. Many are finding that hiring contract research firms can bridge the gap between drug discovery and development, bringing them closer to this goal.

As foundations become more proactive about drug discovery, contract research organizations (CROs) are hearing from them more often, according to Werner Lanthaler, CEO of Evotec, a big German CRO. “What we see is that foundations are extremely professional and caretaking about the right use of every dollar from their constituents,” he says.

In June, Evotec announced that it entered a 5-year partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Under a grant worth approximately $23.8 million, Evotec will generate preclinical data to support the development of new treatments for tuberculosis.

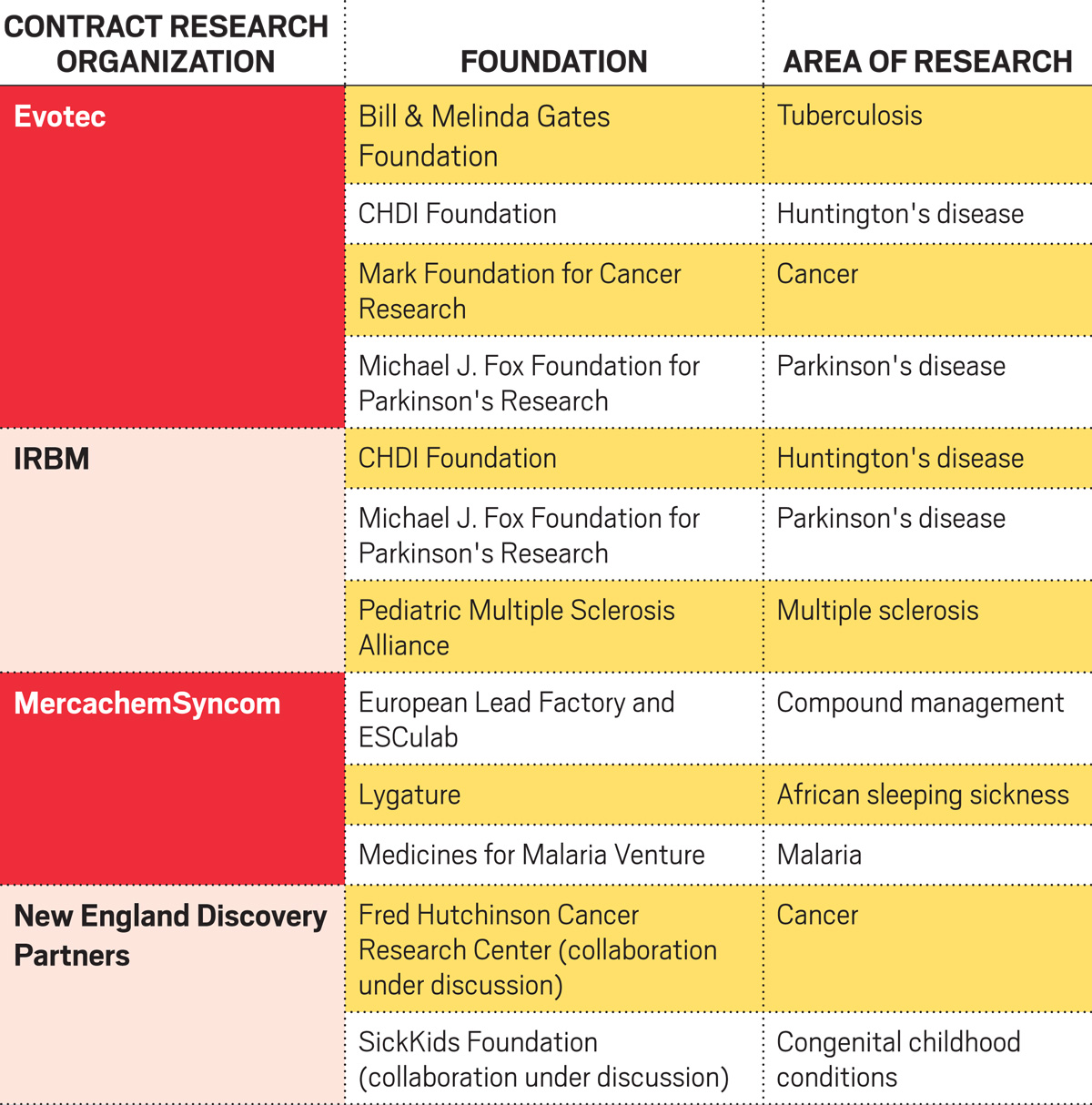

The partnership is the latest addition to a portfolio of about 30 collaborations between Evotec and foundations or nonprofits. They include the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, the CHDI Foundation, and the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research.

For CROs, such relationships might not be as profitable as working with a big pharmaceutical company. But they come with other advantages. Foundations often allow their CRO partners to co-own the intellectual property generated in a project, a rare occurrence in projects with big pharma firms. Evotec, for instance, only covers its costs in some collaborations with nonprofits, but it has the opportunity to co-own the resulting product, if successful, at a later stage.

With this reward strategy in place, a CRO’s project with a foundation is not particularly different from one with a pharmaceutical or biotech company—and it shouldn’t be, Lanthaler says.

“There is a misunderstanding that money under philanthropic projects shouldn’t be managed in the same way as money under commercial projects. But no one can afford to not have the most professional drug-discovery project setup, independent of the motivation that is behind it.”

Foundations, in contrast, see a key difference between working with a CRO and a more conventional academic research partner, says Michele Cleary, CEO of one of Evotec’s collaborators, the Mark Foundation. “With our academic partners, we give grants, but we don’t direct their science. With our CRO partner, we meet frequently to discuss issues and help steer the science in the right direction.”

Founded only 2 years ago by the investor Alex Knaster, the New York City–based cancer research foundation lists Evotec as its only CRO partner, though Cleary says it is “heavily in discussion” with several others. With backgrounds in big pharma, she and the foundation’s vice president of scientific research, Ryan Schoenfeld, have seen the value of working with drug-discovery CROs firsthand and are now reconnecting with old contacts to recruit them for this new cause.

More established foundations already have deep scientific working relationships with CROs. About 12 years ago, CHDI appointed Evotec and Charles River Laboratories as what it calls “integrated partners.” It later added AMRI and IRBM as another two. CHDI trusts these partners to lead its Huntington’s disease drug-discovery projects through all stages of medicinal chemistry, biology, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) studies.

Although these are ostensibly fee-for-service relationships, the foundation sees its CRO colleagues as part of the team, says Celia Dominguez, CHDI’s vice president for chemistry. “The CROs that CHDI collaborates with are the lifeblood of our research,” she says. “They help us develop our therapeutic research plans, and that includes authorship on publications and presentations where appropriate, which is probably different from the relationships that CROs have with pharma.”

CHDI, which currently employs 114 people, about half of whom are PhDs or MDs, charges internal science directors with managing its CRO research programs. It decided against having its own labs because it “needs to be nimble and able to cut therapeutic projects and programs that are not showing promise,” Dominguez says. “Working together with CROs as collaborators has meant we have been able to do this very quickly.”

Partners for good

CHDI’s collaborations with CROs have led, for instance, to the development of a kynurenine monooxygenase inhibitor that could treat both Huntington’s disease and HIV infection. CHDI is now looking for a commercial partner for clinical evaluation of the compound. And Charles River, IRBM, Evotec, and others jointly developed a series of assays that can measure different types of huntingtin, the protein at the root of Huntington’s disease.

Carlo Toniatti, chief scientific officer at IRBM, which grew out of a former Merck & Co. lab in Italy, acknowledges challenges in bringing together multiple research organizations to work on a common goal. “They can lead to overlapping activities and slow decision-making,” he says, "but this can be circumvented by regular meetings."

IRBM has worked with numerous foundations besides CHDI, completing tasks including target identification and validation, mechanism of action studies, generation of cell models of disease, and fully integrated drug-discovery programs.

The ideas for projects usually come from its foundation partners or academics working in the field, “but in most cases they are refined and converted into reality by the CRO’s scientists,” says Heidi Kingdon Jones, IRBM’s vice president of sales and marketing. “The most successful collaborations are those where the new ideas are the result of scientific discussions occurring among members of the foundation and CRO, working together as a really integrated team.”

Established in Switzerland in 1999, Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) has built its business model on working with CROs, says Joan Herbert, senior director for business development at the public-private partnership. For each of its projects, MMV and its development partners devise project plans and then hire CROs to execute them. A drug industry partner handles the submission of any resulting application to regulatory authorities.

“Every MMV project has a CRO element to it because we couldn’t work any other way,” Herbert says. Currently, MMV is working with more than 100 CROs. Herbert says her team shops around for the perfect match, picking the contractor with the right skills for a particular project. “A lot of our compounds have complicated chemistries, and not everybody can work with them. We have to use different CROs with different expertise,” she says.

Historically, developing drugs for malaria—which affects some of the poorest people in the world—has not been attractive to large drug companies, Herbert says. But rather than drop a compound because it’s not easy to formulate and won’t return a profit, MMV can take it to different CROs and try to solve the problem, she explains.

One of MMV’s partners is MercachemSyncom. The 320-employee CRO is headquartered in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and operates a large-scale pharmaceutical chemical plant in Prague. Its collaboration with MMV began in 2015 and targets the development of drugs that block malaria transmission and prevent relapse.

With joint funding from the Dutch government and MMV, the project is profitable for MercachemSyncom and “doesn’t feel so different” from working with other commercial clients, says Rutger Folmer, MercachemSyncom’s director of medicinal chemistry.

But the CRO has also found other advantages to working on nonprofit projects. In a project with the Dutch drug-discovery nonprofit Top Institute Pharma, now a subsidiary of the nonprofit Lygature, MercachemSyncom worked on drugs that treat African sleeping sickness by inhibiting an enzyme called human phosphodiesterase type 4. In this pact the CRO didn’t make a profit, but Folmer says it “started at a time when we were adding medicinal chemistry to our services portfolio and gave us a chance to get our foot in the door, build a team, and market our abilities.”

For the Connecticut-based CRO New England Discovery Partners (NEDP), the attraction of working with foundations stems in part from curiosity. “For us as scientists, it’s an opportunity to work with cutting-edge research and diseases that are underresearched,” NEDP CEO Michael Van Zandt says. He sees potential in bringing together funding bodies, academia, and CROs to translate early-stage programs into projects that big drugmakers would be interested in licensing.

“Academic researchers are very good at discovering new pathways and understanding mechanisms, [and we] are good at improving the compounds and taking drugs from the early-discovery stage all the way to clinical,” he says.

But it can be difficult for a small CRO to crack the nonprofit market, Van Zandt says. His team of 15 people has to spend most of its time with pharma clients—the “bread and butter” of the business, he says—and resources are too tight to spend on applying for funding from foundations or developing nonprofit projects at cost. Nonprofits are often surprised at how expensive it is for a CRO to cover its costs, Van Zandt has found.

Small CROs can be attractive partners for foundations, the Mark Foundation’s Schoenfeld says, because they often have unique, niche capabilities. If they can find a way to get their uniqueness noticed, they might not have to spend their resources on applications because foundations will approach them, he says.

The foundation’s CEO, Cleary, agrees that small CROs have a place in the Mark Foundation’s portfolio. Indeed, she hopes that collaborations between CROs, small and large, and foundations will soon become the norm. “We see these partnerships getting to a point where it’s natural for the CROs to think of foundations as partners the same way they think of pharma and biotech companies,” she says.

Vanessa Zainzinger is a freelance writer based in England.

CORRECTION

This story was updated on Aug. 6, 2019, to better reflect the role MMV plays in its drug development projects with contract research firms. The story was updated on Aug. 8, 2019, to clarify a quote by Carlo Toniatti of IRBM.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter