Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Specialty Chemicals

Movers And Shakers

Chemours’s Paul Kirsch on why his company needs to change and how it will do it

Acknowledging environmental issues, the executive outlines some of the steps that he says will make the firm a role model

by Marc S. Reisch

February 3, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 5

In early December, Paul Kirsch, president of Chemours’s $2.7 billion-per-year fluorochemical operation, walked into C&EN’s New York City office to talk about his firm’s effort to improve its standing in the chemical industry. Head of a business carrying much environmental baggage, he probably wasn’t looking forward to the encounter.

A list of questions that C&EN sent to Kirsch before the interview included queries such as “Why should anyone take Chemours’s social and environmental responsibility pledges seriously?” and “Why is it that the company often seems uninterested in answering reporters’ inquiries touching on the environmental responsibility commitments Chemours claims to embrace?”

Vitals

▸ Hometown: Pittsburgh

▸ Education: BS, mechanical engineering, University of Pittsburgh, 1985; MBA, University of Michigan, 1992

▸ Career highlights: Vice president, XM Satellite Radio, 2004–06; vice president, Hughes Telematics, 2006–09; president, automotive, metals, and aerospace, Henkel, 2009–13; senior vice president, supply chain, Henkel, 2013–16

▸ Current position: President, Chemours Fluoroproducts

▸ Role models: A sister who runs a farm-to-table restaurant and a brother who runs an electronics recycling business

A few months before the interview, Chemours formally launched its corporate responsibility program, which, in addition to Chemours’s fluorochemical business, also covers its operations in the white pigment titanium dioxide and the gold-refining chemical sodium cyanide. The program includes a number of goals targeted for completion by 2030.

Among the program goals are plans to reduce the company’s air and water emissions of fluorinated organic chemicals by 99% or greater, reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 60% and landfill volume by 70%, generate 50% of revenues from products that contribute to United Nations sustainable development goals, and fill 50% of company positions globally with women.

Kirsch, who is also the firm’s corporate social responsibility champion, had the unenviable task of explaining those goals in light of Chemours’s short but bruising history.

Since it spun off from DuPont in 2015, Chemours has repeatedly come under fire for its environmental record. High-profile incidents include a 2017 agreement to pay $335 million to settle 3,550 lawsuits in West Virginia. Plaintiffs claimed they were sickened by drinking water tainted with perfluorooctanoic acid, an ingredient Chemours once used to make fluoropolymers such as Teflon.

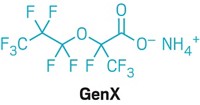

Throughout 2018, Chemours made more headlines because of fluorochemical pollution from its plant in Fayetteville, North Carolina. At one point,the state pulled the plant’s wastewater emissions permit. Chemours currently faces a number of environmental suits from residents living near the plant who say the firm exposed them to potential illness-causing emissions.

But Kirsch says Chemours is committed to turning things around. The firm, he says, wants to be a “different kind of chemical company” and a “role model” for the rest of the industry.

Kirsch says his background prepared him for the corporate responsibility champion job. A mechanical engineer by training, he spent more than two decades working in and around the auto industry. He was involved in taking the communications firm Hughes Telematics public and has a patent from his time there on a device that can remotely turn on vehicle features such as geolocation tracking.

“I’m a transformation junkie,” he tells C&EN. Joining Chemours in 2016 gave him a chance to participate in transforming a legendary set of former DuPont businesses for the 21st century.

Transformation and social responsibility, he says, are in his DNA. His sister has run a farm-to-table restaurant for the past 20 years, and his brother operates a “responsible electronics recycling” business that has diverted more than 5 million kg of used equipment from landfills.

Advertisement

Chemours’s corporate social responsibility goals, adopted last year, are a way to “emphasize our newness” and break with the past, Kirsch says. The goals show “we have both the skill and the will to be a different kind of chemistry company,” he says.

Despite the new goals, the firm suffers from a frequent lack of openness. It rarely responds to C&EN inquiries about its operations. And when Chemours agreed to pay North Carolina $12 million to settle allegations that it had contaminated drinking water with toxic fluoroethers, the company had no public comment.

Kirsch describes the process of coming to the agreement “as first being a listening exercise and then a problem-solving exercise.” Chemours did not think it was important “to spend time talking externally. Frankly, we didn’t see a lot of value in that.” More important, he says, is that “we reached an agreement. I think this is an example of how parties should work together. I hope it gets recognized for that.”

And the firm says it is reaching out to the local community. Last year the North Carolina plant hosted 15 open houses for residents and a like number for local leaders and politicians, Kirsch points out.

It is also putting cash behind its promise to reduce fluorinated organic chemical emissions by 99%. At the Fayetteville facility, Chemours is now spending $100 million through the end of this year to upgrade air- and water-emission controls.

Furthermore, Kirsch says the firm is making “substantial” investments in R&D “to look at nonfluorinated approaches” to its products. One example is Teflon EcoElite, a fluorine-free water repellent for clothing. The alkyl urethane treatment has 60% renewable content, according to the company. More initiatives like it are on the way, he says.

By several outside metrics, Chemours has a way to go to become a corporate responsibility leader. Among the companies receiving an A from CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) for their environmental leadership roles are the chemical makers BASF, Bayer, and Braskem. The investor-backed group says Chemours failed to provide enough information for it to make an evaluation.

The Dow Jones Sustainability World Index includes chemical industry leaders such as Clariant, DowDuPont, Evonik Industries, and Solvay, but not Chemours. Industry observers note that inclusion on the index generally leads to higher valuations of a company’s stock.

The financial data–crunching firm Refinitiv, owned in part by Thomson Reuters, gives Chemours a C rating on its environmental, social, and governance scorecard. Ashland, BASF, and Evonik garner A– ratings.

A consultant who focuses on corporate character says he has hope for Chemours. The firm “appears to be taking the right steps to improve their brand reputation through meaningful action,” says Joseph Torrillo, vice president of Syracuse, New York-based ReputationManagement.com. But, he cautions, “they will only be effective if they show promising signs of improvement toward [their] goals.”

While Chemours has issued its first corporate social responsibility report, Torrillo says it must continue to report on its progress to show it’s taking change seriously and not just promoting itself. “Fortunately, it seems that Chemours has the foundational components in place: they’re actually trying to do the right thing,” he says.

Chemours and its reputation face an uphill climb, but Kirsch insists that it has the determination to follow through on its commitments and become an industry leader. “We’re going to solve this. Just watch us,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter