Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Controlling Charge At The Atomic Level

Surface patterning selectively alters the charge state of silicon atoms, which could help improve electronic devices

by Mitch Jacoby

January 3, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 1

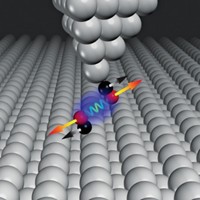

The charge state of individual silicon atoms deposited on a surface can be selectively controlled via nanoscale contacts, according to researchers at Canada’s National Institute for Nanotechnology. The results of the investigation show that a sometimes worrisome silicon surface phenomenon that can hamper the performance of electronic devices can instead be exploited to advance atomic-scale circuitry. Jason L. Pitters explained that unsatisfied electron valencies on silicon atoms—so-called dangling bonds—can dictate the chemical and electronic properties of silicon-based nanostructures. For that reason, researchers would like to be able to control the dangling-bond charge state, which can be positive, neutral, or negative, depending on the number of electrons associated with the dangling bond. By decorating a silicon surface with nanoscale TiSi2 islands, Pitters and coworkers altered silicon’s surface potential and caused a depletion of electrons in the nearest silicon atoms, thereby changing the occupancy of the dangling bonds on those atoms. The team detected the change via scanning tunneling microscopy, which revealed that atoms closest to the islands appeared as bright protrusions, indicating that those atoms’ dangling bonds are uncharged. In contrast, nearly all other atoms on the silicon surface appeared as dark spots, signifying negatively charged dangling bonds.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter