Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Instrumental Efforts

Entrepreneurs take big risks to bring the latest scientific tools to market

by Marc S. Reisch ,

August 8, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 32

The people who take personal risks to bring new scientific instruments to market are a special breed. Many of these entrepreneurs are well-educated scientists who could make a fine living working as consultants or as employees in high-technology companies. Yet they risk their livelihoods and their own money for the chance to start up their own firms.

C&EN interviewed executives from five instrumentation start-ups—XiGo Nanotools, Torion Technologies, Tiger Optics, DVS Sciences, and Semba Biosciences—to glean insights into what drives them to give up a steady job with an established firm for the uncertainties of a new business. Some say they do it for the challenge, to advance technology, or to provide a social benefit. But often the motive is replacing a lost job or defending an existing market position.

Developing new technology is not easy. All the entrepreneurs say they have struggled and made sacrifices as they seek to attract government grants or private capital for their new businesses. Most of the entrepreneurs have met with a degree of success, but some have encountered failure. Many are considering what they will do as their businesses mature and investors come calling for payback.

Finding investors to fund a prototype tool in the first place is particularly challenging. Unlike pharmaceutical companies, which often invest in small medical or diagnostic firms, instrumentation companies typically don’t invest in start-ups.

“The big companies are not interested in bootstrapping a technology from the ground up. But they will buy it when it gets to be a decent size,” says Terry McMahon, principal of PAI Partners, an instrumentation consulting firm. James F. Tatera, head of an eponymous analytical tools consultancy, adds that “for instrumentation firms, buying a successful small toolmaker is cheaper than funding research failures.”

Other sources of money are venture capitalists and angel investors. But venture capitalists often want to see a firm making money before they invest, says Wayne K. Barz, manager of entrepreneurial services for Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Northeast Pennsylvania, a state-supported economic development group.

Angel investors, who are frequently wealthy individuals willing to take a chance on a start-up, have been hurt by the drop in the real estate market, Barz notes, and they have less money to commit these days to a start-up.

The Small Business Administration, a U.S. government agency, is not always helpful to start-ups, Barz says, because it usually lends money secured against a firm’s collateral. Makers of complex medical devices, electronic devices, and lab instruments often need $1 million or more just to build a prototype, he notes, but they often have few assets against which they can secure a loan.

Still, economic conditions don’t seem to hold back the most determined entrepreneurs. They find a way to cobble together the resources they need no matter what roadblocks are in their way.

For XiGo Nanotools, a maker of nanoparticle measurement devices, the going was rough until the firm found a sympathetic ear, a loan, and lab space—all through the Ben Franklin group. The firm was cofounded by Sean Race, a chemical engineer who had been president of the U.S. subsidiary of U.K. particle characterization firm Bohlin Instruments. Race left the firm in 2003, just before it was acquired by Malvern Instruments, and partnered with physical chemist David Fairhurst, who had worked at Brookhaven Instruments.

At the time, Race saw a need for a tool to rapidly measure nanosized particles. He and his partner invested in and formed XiGo in 2004. Friends, family, and some angel investors contributed funds as well. Race hired a small staff of physical chemists, mechanical engineers, and electronics specialists. Money was tight, he recalls. “I was glad to get money from angel investors. Even though some venture capitalists were interested, they wouldn’t put money into XiGo until we had a prototype.”

The early days were difficult. Race and Fairhurst did some pharmaceutical characterization consulting and invested the money they earned into XiGo. Race tried to raise money from New Jersey and Pennsylvania economic development organizations and succeeded only when he found a specialist in the Ben Franklin group who had worked in the particle characterization business.

In 2008, Race secured a first investment of $150,000 from the Ben Franklin group and moved his firm from New Jersey to the incubator in Pennsylvania. Some of the money went to building a prototype; other funds went to beef up staff and software development. Since then, Race has raised $750,000, of which $350,000 came from the Ben Franklin group.

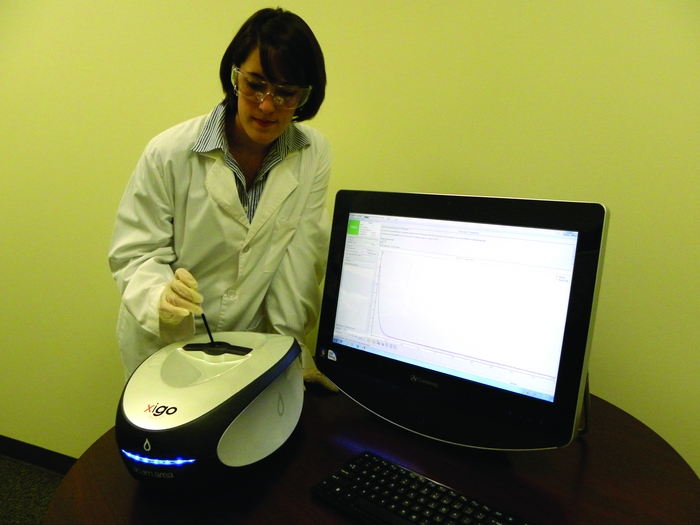

The firm now sells two desktop nuclear magnetic resonance-based instruments for use in labs and on factory floors: the $35,000 Acorn Drop, which measures the size of drops in an emulsion, and the $30,000 Acorn Area, which measures the surface area of concentrated nanoparticle dispersions.

In time, Race says, he would be interested in selling XiGo to a larger firm—such as Agilent Technologies, Horiba, Shimadzu, or Beckman Coulter—that has an existing particle characterization business.

But if he sells too soon, the larger firm might not be fully committed to XiGo’s technology, Race says, because “we could take sales away from their traditional particle measurement business.” Instead, by going it alone for a while, XiGo aims to start taking market share and make a strategic acquirer willing to pay top dollar. “My goal is to be a pain in the neck for those guys. That will be the exit-optimizing price point,” Race says.

Torion Technologies, manufacturer of a portable gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer (GC/MS), already has an exit option mapped out. The eight-year-old spin-off from Utah’s Brigham Young University has granted Smiths Detection, a provider of security instruments to government, the right of first refusal in a sale of the firm, says Douglas W. Later, Torion’s president and chief executive officer.

What started Torion on the road to developing its briefcase-sized GC/MS was a 2003 contract from the Department of Defense to develop a portable instrument capable of identifying chemical threats on the battlefield. Government research contracts kept the company going for the next five years, Later says.

An agreement with the university allowed the company to develop its technology on campus rent-free. The $7 million government funding covered salaries and prototype development, Later says. The firm moved off campus when it began selling a commercial instrument. Now, it has annual sales of $3 million to defense, environmental, and food and fragrance customers.

Torion is profitable, but the past few years have been “tough sledding” because the instrument is new and unfamiliar to nonmilitary customers, Later says. The recession also slowed commercial sales. The firm now employs 25 people, he says. Principals, family, and friends own 75% of the company. Outside investors own 15%, and employees own 10%.

Smiths got its right of first refusal to buy Torion through a 2008 alliance to develop a handheld GC/MS for security, defense, and civil emergency responders. Smiths has experience in selling to the defense and security markets but doesn’t have GC/MS instrument capabilities, so the alliance should be beneficial to both.

But Later isn’t ready to sell just yet. “We’ll probably hang on for another three to seven years to grow the value of the company,” he says.

At Tiger Optics, Lisa Bergson, who is president and CEO, would like to line up a partner for her developing business so it can reach its full potential. Bergson also heads Meeco, a 60-year-old company that makes electrolytic cell-based trace-moisture analyzers for customers such as industrial gas firms.

Tiger was spun off from Meeco in 2001 to develop gas analyzers using continuous-wave cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CWCRDS). But its roots stretch back to the early 1990s, Bergson explains, when a Meeco scientist attended a conference and learned about then-Princeton University professor Kevin K. Lehmann’s work on CWCRDS. That technology, Bergson recalls the scientist telling her and other colleagues, “would replace everything we do.”

Bergson, a business journalist who took over Meeco from her father, physicist Gustav Bergson, said she wanted to know more about a tool that could make her own firm’s technology obsolete. She urged Meeco scientists to get in touch with Lehmann.

The scientist who heard about Lehmann’s work warned that “many of the big instrumentation companies were buzzing around him. He won’t speak to us,” Bergson recalls. But Lehmann did speak to Meeco scientists. “He had a soft spot for small companies,” she says.

Meeco incubated and funded the CWCRDS instrument in its early phases. Tiger started as a Meeco division, introducing its first commercial instrument in 2001. To further develop the technology, Bergson, her husband, and several friends and investors pooled more than $25,000. She also applied for government grants but says she was told the technology “wasn’t feasible.” And she met with angel investor networks and venture capitalists.

Raising capital can be discouraging, Bergson says. “Prospective investors wanted the elevator speech”—the short summary entrepreneurs prepare about their business, its objectives, and profit potential. “I still can’t do it,” she says. “There’s so much to say, and not many people are interested in industrial instrumentation. I’d start and their eyes would quickly glaze over.”

In 2005, Bergson succeeded in attracting two venture capital investors: Expansion Capital Partners and Georgieff Capital. Although Bergson won’t specify how much they invested, she does say that she and her husband retain majority ownership in Tiger.

Last year, Tiger had sales of about $10 million and more than 25 employees. Bergson predicts the firm will be a $100 million-a-year business in six years or so if she can attract the right partners to further expand it. Such a partner might also buy out Expansion Capital and Georgieff Capital, Bergson notes. She also expects to continue playing a role in the business. “It would be painful for me to walk away now,” she says.

A key to Tiger’s success so far is its continuing close cooperation with Lehmann, who is now a chemistry professor at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. “We visit him quarterly and speak to him weekly,” Bergson says. Tiger also helps underwrite students who work in Lehmann’s labs.

For his part, Lehmann, who has no financial interest in Tiger, tells C&EN he considers the work with Tiger mostly beneficial. The firm gives him access to engineering talent that otherwise would be difficult to get. It also helps him keep his lab budget under control by providing components at cost.

But Lehmann does chafe at one aspect of his relationship with Tiger. The firm has asked him several times to delay publishing his research. “This was particularly significant in that I delayed first publication of a CWCRDS measurement for a few years,” he says. “As a result, the first publications using this technique were by other groups who started working on CWCRDS after my laboratory.”

For DVS Sciences, a recent University of Toronto spin-off and developer of a $600,000 high-throughput mass cytometer used in drug discovery, no such conflict exists between scientist and commercial developer because they are one and the same.

Scott Tanner, CEO and cofounder of DVS, says he and colleagues developed the intellectual property on which the firm is based in 2000 while he was principal scientist at MDS Sciex, now AB Sciex. In 2004, he and three other founders, all from MDS, formed DVS and licensed the firm’s fundamental technology from Sciex. They moved to Canada in 2005 to further refine the instrument, a specially configured inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometer.

Tanner, who is himself a Canadian with a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from Toronto’s York University, says the University of Toronto was an ideal spot to further develop the instrument, called the CyTOF, and the accompanying reagents. “They were the perfect partner,” he says. The school was at the heart of a health care network and offered opportunities to work with its chemistry department and business school.

While he was at the university from 2005 to 2010, Tanner was also a professor of biomedical engineering and then a professor of chemistry. To support development of the CyTOF, he got $17 million in grants from Canadian government entities such as Genome Canada and Ontario’s Ministry of Research & Innovation.

Advertisement

Earlier this year, DVS raised another $15 million. Investors include the investment firms Mohr Davidow Ventures and 5AM Ventures and the venture capital arms of Roche and Pfizer. All told, DVS has raised about $40 million since its inception from grants, venture capital funds, and the sale of seven instruments, Tanner tells C&EN.

Along the way, DVS developed three prototype instruments before settling on the final design. It also went through eight generations of reagent development. DVS has built a facility northwest of Toronto capable of building 100 CyTOF instruments annually. “We expect to fill that capacity in three years,” Tanner says. And he predicts that revenues will hit $100 million annually in four years.

Tanner knows that investors want to get a return on their money, preferably in the next three to five years. “We could be acquired or we could do an initial public offering of stock,” he says. He has already spoken with some companies about a deal and suggests potential buyers could include Life Technologies, Agilent, and Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Tanner does not think the venture capitalists’ expectation for a quick payback is onerous. “The goal is to make money and be profitable. If venture capital firms put a target payback period in place, that’s fine. My company benefits as well,” he says. “It’s not a one-way street.”

Semba Biosciences, like DVS, was started by scientists who sought new opportunities. Two former UOP chemical engineers, Anil Oroskar and Ken Johnson, long dreamed of starting a company that would make a benchtop simulated-moving-bed chromatography (SMBC) instrument. They got their chance when Oroskar and former colleague and venture capitalist Johnson cofounded Semba.

Since the 1960s, SMBC has been used for large-scale separations in the petrochemical and sugar industries. But a smaller instrument could speed lab-based separations as well as larger-scale protein purifications and chiral drug separations.

Johnson and Oroskar hired Robert C. Mierendorf as president and CEO of Semba in 2006. Mierendorf also comes from an entrepreneurial background, having sold Novagen, a molecular and biological reagents company he founded, to Germany’s Merck a few years earlier.

With advice from Johnson and Oroskar, Mierendorf hired engineers and scientists to develop Semba’s benchtop SMBC instrument which was introduced in 2009. Johnson’s Kegonsa Seed Fund along with Oroskar and other angel investors have supported the firm since its inception.

Today, Semba has 13 employees and is almost profitable, Mierendorf says. He isn’t ready to talk about an exit strategy yet, saying the firm has a lot of nitty-gritty work to do before it is ready for the next step.

“We’re a small company and we need to develop a greater market presence. So we are pursuing more interactions with labs to develop scientific credibility,” Mierendorf says. “We want to get the instrument used by academicians and others who will publish their results.”

Like other start-up instrumentation firms, Semba’s greatest challenge, besides raising cash, is marketing its products. Getting the word out on new technology to potential customers isn’t easy, but it is one of the things entrepreneurs must do to develop sales and make money for themselves and their investors.

Entrepreneurial Scientist Perseveres Despite Setbacks

Tim D. Gibson is hoping that the third time will be the charm for an electronic nose he had a hand in developing.

Gibson and some partners have just started a new firm, AutoNose Manufacturing, to sell the third generation of the odor characterization instrument. AutoNose is the successor to Scensive Technologies, which closed down earlier this year. Gibson and partners, who had worked for Scensive, just bought Scensive’s patent portfolio.

The electronic nose business got its start as Bloodhound Sensors, but that company faltered in 2001. It was revived as Scensive by the British venture capital firm Viking Fund Managers and smaller investors. Scensive ran out of money early this year and went into bankruptcy reorganization. “We weren’t able to get enough sales for a long-term sustainable business,” Viv Hallam, managing director of Scensive, tells C&EN.

Gibson is a member of the biological sciences faculty at the University of Leeds, in England, where he helped develop the conductive-polymer-coated silicon chip at the heart of the electronic nose. Now associated with three firms trying to commercialize the technology, he is undeterred by the earlier failures and subscribes to the notion that if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.

A serial entrepreneur, Gibson is also technical director of Elisha Systems. In 2008, Elisha was spun off from a $4 million European Union-financed project to develop biosensors using antibody-based chips to rapidly detect disease biomarkers with a pocket-sized chip reader.

Elisha has three employees now and is on the cusp of both commercializing its technology and seeking financing. If all goes well, the business could be worth tens of millions of dollars in four years, Gibson says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter