Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Acidic Ocean Hits Pacific Northwest

Changes in ocean chemistry threaten Washington state’s Makah tribe as well as the region’s shellfish industry

by Eric Niiler

March 25, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 12

Experience Cape Flattery's crashing waves, and watch Micah McCarty use his trusty pocket knife to gather shellfish there.

The path to Cape Flattery is a twisty, moss-carpeted tunnel underneath red cedar and Douglas fir trees that crowd Washington state’s rugged coastline. Micah McCarty scrambles down the forest trail to a shoreline below, leaping across tide pools and slippery rocks to a point where waves break on shellfish beds. We’ve reached the northwesternmost point of the U.S. mainland, a craggy tip of the Olympic Peninsula that belongs to the Makah tribe.

This group of Native Americans has been fishing and harvesting here for the past 2,000 years. McCarty, the tribe’s 42-year-old former chairman, pulls out a pocket knife and squats down to scrape a handful of mussels and barnacles into his hand. “We call them slippers and boots,” he says. “I’ll make them into a Makah paella tonight.”

McCarty and his family grew up picking these marine delights along the coast. Oysters, clams, cockles, barnacles, and other types of mollusks and shellfish have always been part of the Makah diet, as well as the tribe’s culture. The shells are used both as beads in ceremonial regalia and as musical instruments. But now, changes in the global climate have led to rising ocean acidification that has put in peril the future of the Makah harvest.

“It’s already starting to impact the way that the shellfish cling to the rocks,” says McCarty as he points to a group of “boots.” The gooseneck barnacles are a species with a flexible orange “neck” that attaches itself to the wave-tossed rocks. “They can’t hold on very well. When the waves hit, you see there’s very few left of that colony.”

McCarty isn’t a scientist, but his observations here at Cape Flattery confirm what marine biologists and chemists are finding across this region and the globe. Increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are reacting with seawater and lowering its pH. That increasing acidity is damaging shellfish, coral reefs, and other marine animals.

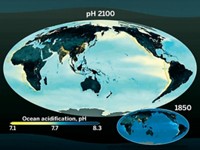

Over the past 250 years, the average upper-ocean pH has decreased by about 0.1 units, from about 8.2 to 8.1. This drop in pH corresponds to an increase in the acidity of about 30%. Unless things change, scientists predict the average acidity of the surface ocean will be more than double preindustrial levels by the end of this century, according to the federal 2013 National Climate Assessment.

When CO2 levels in seawater rise, the availability of carbonate ion decreases. That change makes it more difficult for marine organisms to build and maintain shells and other hard body parts from calcium carbonate. If the carbonate ion level drops too low, seawater corrodes the shells. The animals have higher mortality, and juveniles and larvae are most at risk. Any die-off could have devastating effects on Washington’s $270 million shellfish and aquaculture industry.

In the Pacific Northwest, the problem of ocean acidification is especially bad for several reasons. One reason is that prevailing winds push surface waters away from the coast, causing a local upwelling of carbon-rich water from the deeper ocean to the surface. This upwelled water is naturally rich in nutrients, is high in CO2, and has low pH. But now, the upwelled waters are also carrying an ever-growing load of human-generated CO2 picked up from the atmosphere 30 to 50 years ago when the water was last in contact with the atmosphere. As a result, deep water today is more corrosive than ever to shell-building organisms such as oysters, clams, scallops, mussels, crabs, abalone, and pteropods (small sea snails eaten by fish and other marine life).

A separate acidification process is under way in the vast expanse of Puget Sound, just as in other estuaries along the world’s coastlines. Runoff from farms, storm sewers, and urban pollution flushes organic carbon and other nutrients into estuaries that are nurseries to growing shellfish. These nutrients fuel blooms of marine algae, which then die, fall to the bottom, and during decomposition result in more CO2 being released to the water. In the air, emissions of nitrogen and sulfur oxides from factories, cars, and power plants are yet another source of nutrients that cause blooms that lead to more acidic waters.

The chemical soup resulting from all of these acidification processes has made both Puget Sound and the Washington coastal area among the most acidic waterways on the planet, according to Jan Newton, senior principal oceanographer at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory.

“Because we’re increasing the anthropogenic contribution of CO2, that pushes the concentrations in the ocean higher and higher,” Newton says. She explains the twin dilemmas of Washington shell fishers—upwelling along the coast and eutrophication in the estuaries—that are lowering the pH of both areas.

“The concern is, Will the biology be more susceptible and change, or is it possible that some of our outer coast species will be resilient?” Newton asks. “Are we at their threshold? Will we reach it in five or 50 years? Nobody knows that, but the risks are there.”

Newton is directing a network of ocean-monitoring buoys along parts of the Washington coast and Puget Sound that are giving researchers more information about hot spots of acidity. She’s also working with the Makah and three other Indian tribes to serve as eyes and ears to changes already under way. Some tribal members are helping deploy the massive buoys on oceanographic cruises, crunching numbers along with researchers and reporting their own data about abundance of the marine species they rely on.

Because the Makah and other tribes have long oral and written histories of the status of their surrounding environment, they have been able to fill in gaps for researchers such as Newton who are studying the ocean changes. Tribal members are providing scientists anecdotal, yet vital, data about the abundance of marine organisms like clams, mussels, and other shellfish that they have harvested for generations.

Turning observation into action on this issue is a bigger step, according to Chad Bowechop, director of the Makah tribe’s marine resources commission. “We are seeing certain things around here,” he says. “We’ve recognized that some of our mussels and boots aren’t as plentiful around Cape Flattery. The biggest question is, What can we do about it?”

The problem hit home a few years ago for Washington’s commercial shellfish growers. From 2005 to 2009, billions of oyster larvae died in hatchery tanks, which are filled from the ocean. At first, growers in Oregon and Washington thought the problem was a killer bacterium, but researchers finally figured out that the ocean chemistry was to blame. The increased CO2 levels in the seawater prevented the larvae from building the calcium carbonate body parts they need to grow and live.

As the extent of the damage became known, political leaders in Washington grew worried. The state’s shellfish industry—oysters, clams, and mussels—accounts for $270 million in direct sales. And any damage to shellfish or other small shell-building organisms would also hurt the larger salmon-based seafood industry, which contributes $2.4 billion and 42,000 jobs to the regional economy, according to state figures.

Policymakers have known for several decades that acidification would likely be a problem sometime in the future. They’ve been tracking problems on coral reefs, for example, in other parts of the world. But many in the Pacific Northwest were surprised by the sudden oyster hatchery die-offs.

“Scientists predicted the ocean chemistry would change and there would be impacts, but I don’t think they anticipated it would happen this soon,” says Hedia Adelsman, executive policy adviser for the Washington State Department of Ecology.

After the oyster larvae disaster, then-governor Christine O. Gregoire appointed a blue-ribbon panel to come up with policy recommendations to prevent an economic collapse. The final report released in November 2012 called for a mix of local and global solutions, research, and action.

Before leaving office in January 2013, Gregoire signed an executive order directing $3.3 million to help shellfish hatcheries keep their water-monitoring devices operating, to create an acidification research center at the University of Washington, and to begin cutting pollution into Puget Sound. The plan also calls on the federal government and Congress to do more to control carbon emissions that are causing acidification.

Conservation groups applauded Gregoire’s action, which they say is the strongest so far in the U.S. The Ocean Conservancy’s Julia Roberson says that absent any help from the Congress or the White House on climate change, it’s up to individual states to take the first steps. The 158-page report issued by Gregoire’s blue-ribbon panel “is a road map for local action on ocean acidification that hopefully other states can pick up and use,” Roberson says.

In the tribal town of Neah Bay, just five miles from Cape Flattery, the Makah hope the road map isn’t coming too late. Unlike commercial shell fishers, the tribe’s 1,200 or so members can’t pick up and move their harvesting areas outside the boundaries of their existing reservation. So any environmental change along their protected stretch of coastline hits them particularly hard.

Many Makah families fish for salmon and other commercial species from the port at Neah Bay. They also eat shellfish and collect shells for tribal ceremonies several times a year. Artisans rake the sandy beaches for the olive shells that they transform into colorful necklaces, headbands, and other regalia important to the tribe. Some worry that the shells might not be around in the future.

“It’s hard to imagine that would happen,” says Janine Ledford, director of the Makah Cultural & Research Center. “We just take it for granted that olive shells have always been here and always will be.”

For his part, McCarty says the tribe’s great strength is its ability to adapt. In recent years, the tribe’s natural resources have been threatened by oil spills, overharvesting, and illegal poachers supplying the Asian seafood market.

“We’ve been adapting to these challenges for a long time,” McCarty says as he stands on the rocks looking across the Pacific Ocean. “We are resilient people and we keep our dependence on what we know.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter