Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Earthworm’s Glow Unearthed

A new type of luciferin gives Siberian worm a blue hue

by Bethany Halford

April 28, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 17

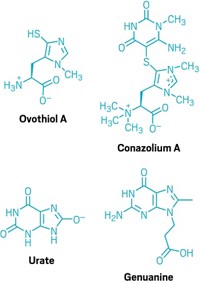

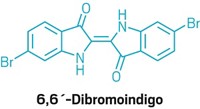

In the forest soils of Siberia, there is a tiny worm that will emit blue light if given a little tickle. The critter, known scientifically as Fridericia heliota, gets its glow via the oxidation of a previously unknown luciferin compound facilitated by a luciferase enzyme. This is the same mechanism that many bioluminescent creatures, including fireflies and certain jellyfish, use to produce so-called cold light. To date, only a handful of luciferin analogs have been chemically characterized. Researchers led by Ilia V. Yampolsky of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry wanted to know precisely which chemical made F. heliota glow. The team collected approximately 60,000 of the little worms, each of which is only about 15 mm long, and then extracted their bioluminescent components (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201400529). The researchers were able to isolate only 0.005 mg of the color-giving chemical from which they could do limited NMR and mass spectral analyses. Using these studies, they narrowed down the structural possibilities to four isomeric peptides and then synthesized them. One of the synthesized compounds (shown) turned out to be a match with the natural Siberian worm luciferin and produced light when mixed with crude Fridericia luciferase.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter