Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

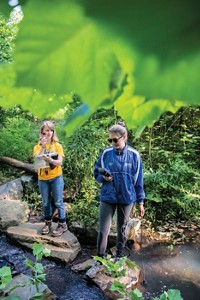

Citizen Science Faces Pushback

Some states are restricting the collection or use of environmental monitoring data

by Steven K. Gibb

September 14, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 36

Amateur scientists such as England’s Mary Anning have been collecting scientific information and making discoveries going back centuries. Anning, a destitute collector of seashells and fossils near the seaside town of Lyme Regis who lived from 1799 to 1847, is credited with finding the first remains of dinosaurs such as Ichthyosaurus, Plesiosaurus, and Pterodactylus macronyx, a flying reptile. She and countless other amateurs have gathered botanical, wildlife, geographical, and mineral information that has helped shape knowledge about the world.

COVER STORY

Citizen Science Faces Pushback

Nowadays, this trend of citizen-collected science data is booming thanks to the proliferation of mobile phone apps and online crowdsourcing platforms. Examples include the Marine Debris Tracker, which warns boaters and swimmers of obstacles, and Project Noah, an acronym for “networked organisms and habitats,” which explores and documents wildlife.

But some elected officials are rebuffing this trend regarding collection of data on pollution levels. Some states have adopted laws that either constrain citizens from collecting environmental information or impose tough standards on state regulators who plan to use it.

Modern-day citizen scientists help professional researchers track bird migration patterns, collect local air quality and climate information, document fish kills, and much more, says Greg Newman, a research scientist in plant ecology at Colorado State University and leader in the burgeoning movement. Newman is studying how citizen science research is impacting state and national regulatory decisions and is finalizing a paper for publication. He is evaluating the collection, management, and visualization of data gathered by volunteers.

Newman is also facilitating citizen science. He has received National Science Foundation funding since 2007 to build the CitSci.org website, which provides a support platform, data templates, and other tools to facilitate what he calls “all kinds of flavors” of citizen science. The template can be used for any project, from the frequency of hip dysplasia in specific dog breeds to measurements of chemicals in water bodies. To date, almost 200 information collection projects have been launched through CitSci.org.

Volunteers often express their curiosity by collecting information on the natural world. “Concerned citizens that think certain things should be measured play a role in how knowledge is generated and communicated,” he says.

A leader of a California-based citizen science group agrees. “The most common feedback we receive from state agencies is that we do excellent communications and outreach work on water quality,” says Travis Pritchard of San Diego Coastkeeper, which monitors water quality in the city’s beaches and inland waterways. In contrast, state agency communications are often constrained by bureaucratic references and political caution that do not paint a compelling picture about water quality conditions, he says.

But even as the trend of volunteer data collection expands, some are skeptical of this science and its value to those who set environmental policy such as pollution limits for waterways. Chris Yoder, research director at the Midwest Biodiversity Institute in Ohio, is evaluating citizen science programs in 25 states to determine whether the data being produced is rigorous enough to support federal Clean Water Act determinations for pollution in water bodies. Under that law, states must file reports on the pollution levels and condition of each water body every two years.

“It’s uncomfortable to go against something so popular, but people may not be thinking things through and looking at the information dispassionately,” says Yoder, who has more than two decades of experience doing contract monitoring work for the Environmental Protection Agency and state environmental agencies. “What they can do and what they should not do needs to be asked,” he adds.

In particular, Yoder is concerned with how agencies and courts may respond to litigation challenging regulations setting strict water pollution caps that are based on information collected by volunteers.

Some state regulators are hampered or barred from using data collected by citizens. For example, in Yoder’s home state of Ohio, the General Assembly unanimously passed a “credible data” law in 2003. The statute mandates that state agencies only use water impairment data gathered by a qualified collector and involves techniques that require extensive training such as sediment chemistry and habitat assessment for water bodies.

“The concept that the state should have as much good scientific information about our surface waters as possible in order to properly manage them was a primary reason for the legislation,” the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency says in a statement. “Ohio EPA uses the data submitted through the [credible data] program in several ways dependent upon how the data were collected and whether they meet various review standards.”

Yoder says such data requirements can help ensure that environmental decisions are worthy of public investment. One example is whether to replace old sewer systems that have interconnected sanitary and storm drains that lead to sewage-tainted overflows during heavy rainfall. “If a metropolitan water district is willing to spend $100,000 to reduce combined sewer overflows during storms, is that a good investment based on reliable data?” he asks.

But others are opposed to such laws, saying they hamper the ability of agencies to forge partnerships to solve environmental problems.

In September of 2011, a power outage in San Diego disabled pumps that resulted in two major sewage spills and collectively released 1.9 million gal of waste, closing beaches and polluting inland waterways.

Pritchard of San Diego Coastkeeper had baseline and other monitoring data that allowed water managers to address the problem. Pritchard says that if a law such as Ohio’s existed in California, the 2011 spills would not have been adequately addressed.

“We were the only ones with baseline data about sewage levels at the two concerned sites, and the municipal government used the data our volunteers collected to benchmark their cleanup and restoration effort,” he says. Pritchard points out that these types of partnerships can be leveraged inexpensively to address unforeseen developments.

Ohio is not alone in acting against data collected by citizens. Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming have laws that prohibit citizen scientists from collecting environmental information near agricultural sites. These data could possibly affect cattle farmers whose herds spend time in and near streams and rivers.

“The motives may not be noble, as agricultural companies seek to curtail ‘guerrilla sampling,’ near their facilities,” Yoder says. “But rigor is needed to avoid sloppy water quality programs.”

Wyoming’s law actually criminalizes the collection of data from public lands no matter whether the area is owned by localities, the state, or the federal government. Wyoming Outdoor Council attorney Lisa McGee, says the law is “ripe for challenge.” The council tracks land policies in the state, and McGee says it has received multiple calls from state and federal government field researchers concerned about securing permission to access public lands under the law so they do not violate provisions against trespassing. “The law is overbroad and vague in prohibiting state and federal employees from collecting field data on public land,” McGee says.

Although a handful of states are moving against data collection by citizens, federal EPA officials stand in contrast. They say they are excited by the growing number of data collection programs run by states, environmental groups, and other federal agencies, including those that gather data on air pollution. “The academic literature suggests that biases are not a major problem with data collected by nonprofessionals. EPA has actively engaged citizen science with our next-generation monitoring, particularly air sensors. EPA researchers are testing these low-cost, portable instruments in the lab and the field and piloting projects in Newark, N.J.,” an EPA spokeswoman says.

In March, EPA provided air-monitoring devices for volunteers in Newark to gather data on nitrogen oxides and particulate matter in air, with an eye toward understanding the incidence of asthma attacks in the community. A quarter of Newark’s children suffer from asthma, three times the state average, and asthma accounts for the leading cause of absenteeism for the city’s school-age children, according to the agency. EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy says, “Community-based air-monitoring projects like this one make public health a priority and pay multiple dividends. We not only gain valuable information, we also help community members gain the skills and experiences they need to conduct citizen science projects in their communities to better protect their families.”

Although EPA officials say efforts to promote citizen science are growing within the agency, other sources say they have shrunk. Each of EPA’s 10 regional offices, which are scattered across the country, formerly had a citizen science coordinator. Now there is only one person in the agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters charged with that responsibility.

But Mark Bagley, a scientist in EPA’s research office, says that although that role may not be formally written into an employee’s job description, there are plenty of champions “carrying the torch” for citizen science in the agency’s regional offices. Across EPA, monthly seminars are held along with other efforts to advance trust between citizen science groups and EPA officials, says Bagley, who has a paper in press based on a 2013 EPA citizen science workshop.

National groups dedicated to advancing citizen science also have begun to form. Newman serves on the board of the new Citizen Science Association, which held its first meeting in San Jose, Calif., last February and is planning a follow-up in 2017. And the growth in the trend isn’t confined to the U.S. A European Citizen Science Association and Australian Citizen Science Association have recently sprung up too.

Citizen scientists in the U.S. are augmenting the reach of regulatory agencies and natural resource managers by collecting extensive site data. Volunteer-collected data are adding to knowledge concerning climate dynamics, pollution spills management, and water quality. While some states are curtailing the use of citizens’ data, many others are tapping into and leveraging the efforts of volunteers to help government agencies make more evidence-based decisions that have the potential to slash pollution and engage communities.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter