Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

Differing Perspectives

Two ACS members—one who graduated this year, and one who graduated 30 years ago—reflect on prospects for chemists

by Andrea Widener

November 9, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 44

Shahriar Mobashery, University of Chicago, 1985

When Shahriar Mobashery got his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1985, chemistry seemed like a great career choice.

“I thought the future was open,” the University of Notre Dame chemistry professor remembers. “In retrospect, that optimistic perspective was wonderful.”

Back then, graduate schools had a hard time keeping students from dropping out for high-powered jobs in industry. Even foreign students in need of visas were in high demand. “Everybody got jobs in the 1980s,” he remembers.

But the optimism that pervaded chemistry departments when Mobashery was in grad school has since dissipated. “Our outstanding students and postdocs still do just fine,” Mobashery says. But average students don’t fare nearly as well.

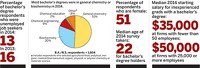

As the ACS ChemCensus shows, unemployment for chemists is higher today—3.1% in 2015 versus 1.7% in 1985. And when inflation is taken into account, the average salaries have been basically flat since Mobashery graduated.

But there are complex factors at play, he says. Globalization has pushed some jobs overseas, and there is less competition among companies to develop new products. Mobashery points to his own field—antibiotics—as an example. When he graduated in 1985 several dozen companies competed with each other to make new antimicrobials. Now, there are just a few.

But that doesn’t mean he’s not optimistic. The diversity of the field is increasing, which suggests that chemistry is a welcoming place, Mobashery says. As the ChemCensus shows, ACS has become more diverse; the percentage of women is up from 15% in 1985 to 31% in 2015, and almost 20% are now from minority groups, up from less than 10% in 1985. “The trend is in the right direction,” he says.

More important, the research opportunities have never been better than they are today, Mobashery says. “If I were an assistant professor now, I could take my research in 100 different directions,” he says. “There are so many things one could do, it is mind-boggling.”

Jenny Zhang, University of Washington, 2015

Jenny Zhang knows she was lucky to land her dream job after graduating earlier this year.

Zhang, who received a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Washington, is currently mixing her science background with business in a two-year global consultant training program at EMD Millipore, part of Merck KGaA. There, she is learning how to be a management consultant while getting exposure to many different parts of EMD Millipore’s business. “I have always wanted to transition from the pure technology to more of a bridging position,” she says.

Early on, Zhang knew she wanted to go into industry, and she prepared by taking M.B.A. classes and doing business internships while she was getting her Ph.D. But even then, “I was not clear if there was a job out there for me,” she says.

Not all of her fellow graduates have been able to find the job they’ve been searching for, Zhang says. They might be teaching part-time at the test-prep service Princeton Review or at a community college, doing computer programming, or carrying out a postdoc.

That picture fits with what the ACS ChemCensus data suggest about employment opportunities in 1985 and 2015. “It’s a lot harder to get hired with a Ph.D. in chemistry today,” she says.

“It is rare to hear about someone who finds a high-paying industry position or who goes directly into a tenure-track assistant professorship,” Zhang continues. “I see a lot of colleagues end up taking a job where I would expect they would end up in a better position.”

Now that she’s in industry, Zhang finds it’s harder to stay connected to ACS because many of the society’s events are held on university campuses or at national and regional meetings.

Zhang has seen for herself one of the trends pointed out by the ChemCensus data: The number of female chemists is increasing. Although just a few women hold top-level management positions, she says there are a good number in lower and middle management these days. Among her colleagues at the entry level, it’s about equal numbers of men and women. “You don’t really feel a gender difference.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter