Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Education

Coming out in chem class

Chemistry teachers who reveal their LGBTQ+ identity to their classes encourage queer students to stay in STEM

by Katherine Bourzac

June 19, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 25

On the first day of introductory chemistry, assistant professor of instruction Stephanie Knezz shows students at Northwestern University a slide depicting famous chemists. The faces she displays represent some of the field’s foundational equations and phenomena: Avogadro and his famous number, Boyle and his foundational law, Bohr and his acclaimed atomic model. Chemistry textbooks are filled with the discoveries of white men like these. And students will recognize that fact whether she points it out during her lecture or not, Knezz says.

Her slide also has a faceless silhouette labeled with a question mark—a place for future, more diverse chemists to fill in. She wants her students to know that even if they don’t look like one of the great historical chemists, they, too, can be scientists and perhaps even make discoveries that will end up in textbooks. “Now you have the chance to do this. How awesome is that?” she asks them.

This desire to foster students’ sense of belonging in chemistry is also why Knezz comes out to her students during the first session of class. “The student has to feel connected to what they’re learning,” she says. When she’s authentic, Knezz contends, all the students connect to the material more.

The disclosure has a deeper impact on some of her LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) students and those who are questioning their identity. These students may be meeting an out scientist for the first time. “I try not to make a big deal about it—I bring it up in a list of things,” she says. Knezz, who identifies as pansexual, also shares where she went to school and that she was a first-generation college student. She wrote about her approach recently in the Journal of Chemical Education (2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00846).

The lack of LGBTQ+ representation in science has real consequences: queer students have a harder time identifying as scientists and are more likely to leave these fields, according to surveys. (“Queer” is an individual identity; it’s also commonly used as an umbrella term for people with a minority gender identity or sexual orientation.) One study found that, compared with heterosexual peers, 7% fewer sexual-minority students remain in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors by the end of college (Sci. Adv. 2018, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aao6373). That’s in spite of the fact that they are more likely than their straight peers to participate in undergraduate lab research experiences, which typically lead to higher STEM-major retention rates, says Bryce Hughes, an education researcher at Montana State University who performed the research. After controlling for this, Bryce found that queer students are about 10% more likely to leave STEM majors.

A growing group of queer educators and allies is working to change this. Many, like Knezz, want to give students the out-and-proud role model they didn’t have but would have benefited from. “When you’re out, you are opening that door for students to come out,” says Daniel Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano, a senior instructor who teaches organic and general chemistry at the University of South Florida.

Changing the culture

For queer students, science departments and college in general can be a hostile environment. Kyle Trenshaw, an educational development specialist at the University of Rochester, realized he was trans when he was a chemical engineering undergrad. He decided he wasn’t coming out after hearing his roommate’s boyfriend saying cruel things about a trans woman in their class. Trenshaw concluded it wasn’t safe to talk about his identity and that science might not be a place for LGBTQ+ people.

Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano, who is gay, was out in college. In the days leading up to a field trip, he found out that some of the science faculty were making fun of him and another gay student. “It makes you think twice” about belonging in science, Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano says. “I never knew any out professor or mentor of any kind.”

out, you are

opening

that door for

students to

come out.

Even for those who don’t experience such personal insults, chemistry and other STEM fields can feel chilly. In science, talking about personal identity is often seen as unprofessional. But this idea of not talking about identity is based on the premise that everyone is straight and cisgender (people whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth). This attitude creates a stressful work, classroom, or lab for queer scientists and students, Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano says. “It is exhausting to compartmentalize what you can and can’t talk about,” he says. “Straight people are not asked to do that.”

“In STEM, because nobody talks about it, everyone is labeled cis and straight,” Trenshaw says. Being in the closet takes a lot of energy. Trenshaw describes a typical train of anxious thought: “Am I going to come out to this person today? Am I going to have to correct my pronouns?” Will the reaction be benign, or “are they going to call their buddies to throw bricks through my window?”

Because of the stress of being closeted, “a brilliant scientist is wasting their brainpower on making sure they seem straight, that they don’t make people uncomfortable,” Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano says. He helped analyze interviews for a research project called Queer in STEM, which surveyed 1,427 professionals. Difficulty navigating separate professional and queer identities was a common theme (J. Homosexuality 2019, DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2019.1610632).

For scientists, then, it can be unsafe, or at least nerve racking, to come out. That in turn means LGBTQ+ students often don’t have any role models to identify with—and are more likely to move to other departments or drop out of college, Montana State’s Hughes says. When students walk down the halls of the English department and see “You are welcome here” signs on every faculty member’s door, and only a small number of those signs appear in the science and engineering departments, the message they pick up is not that scientists are objective but that queer students may not be welcome or may even be unsafe, Hughes says.

LGBTQ+ students are more likely to enter college and the workforce at a disadvantage, says Eric Patridge, a chemist who cofounded the national organization Out in STEM (oSTEM) in 2005. Those who grew up in a family or a community that did not accept them might not have gotten the same level of support and leadership opportunities as straight, cis students, he adds. Through its campus chapters, an annual conference, and other activities, oSTEM provides queer students with leadership opportunities they can put on their résumés, Patridge says. For example, student leaders learn fundraising and organizing skills by assembling a team to attend the conference and seeking travel funds and other financial support from their universities.

Last year, about 700 people attended oSTEM’s conference. This event in particular provides an opportunity for students to see consonance in their professional and personal identities, Patridge says. “For some of them, it’s the first time they can be themselves, and it’s not a club or a bar—it’s a professional space,” he says.

Rob Ulrich, a biogeochemistry PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles, says graduate school can be isolating for queer students, even in large, politically progressive cities. “Chemistry is a hard major,” he says. “All your energy goes to school and research. To even go a few miles away to the gay neighborhood is hard” because it’s time consuming. There may be a lot of queer people in Los Angeles for students to interact with, but there might not be any other queer people in the students’ own labs or classrooms.

At a Cookies and Queers event for new students in 2017, Ulrich, who is gay, saw tables for groups organized around interests in the arts, the humanities, and political activism—but no organization for LGBTQ+ science students. “I walked right back out,” he says. And he started his own group. Queers in STEM runs networking events, lightning talks for students to get practice presenting their research, and field trips. They’ve learned about native plants at a local nature reserve and had a private astronomy tour.

Anecdotally, at least, these programs work. oSTEM gives students connections and experiences that lead to career opportunities, Patridge says. Hughes says more data about queer students’ experiences in STEM would be helpful. Neither the US Department of Education nor the major private educational data-gathering organizations collect data about sexual orientation or gender identity. Historically, it would have been dangerous to do so. Today, the reasons are political, Hughes argues.

Hughes says his study on STEM retention was based on one of the first college surveys to include information about sexual orientation, but he notes that the data were limited. That survey, carried out in 2011 and 2015 by the Higher Education Research Institute, queried students when they entered college and again only when they finished. Although it asked about sexual orientation, it did not ask about gender identity. Students who dropped out were not included, nor were, for example, students at community colleges. And queer students were not interviewed about why they changed majors or what encouraged them to stay in STEM. Hughes and other sociologists and education researchers are working to fill in the gaps; more data are coming, he says.

The US National Science Foundation has announced it will start a pilot project to collect data about LGBTQ+ status on the national Survey of Earned Doctorates, possibly as early as 2021. The move was spurred by an open letter, signed by 17 scientific organizations and 236 scientists, requesting that NSF collect these data. For the general population, numbers vary; a 2011 survey by the Williams Institute estimated that 3.5% of Americans identify as lesbian, bisexual, or gay, and another 0.3% as transgender. That amounted to about 9 million people. A larger group, about 11%, said they experienced same-sex attraction. LGBTQ+ people are “a big sector of society, and we should probably learn more about them for when we’re making policy decisions,” Hughes says.

Without more data about what helps LGBTQ+ students in particular feel welcome in science, Hughes says educators can turn to broader sociology research about diversity and STEM retention. For minority students to stay in these fields in school and in their careers, they need to be able to identify as a chemist or a technologist or a mathematician. Diverse students need diverse role models. For that reason, efforts like oSTEM and the individual actions of faculty who come out are important. “It’s critical to have mentors, and it’s critical for faculty to be able to be open about who they are,” Hughes says. “In instances where you have somebody willing to take that risk, it has an impact on students.”

Out in STEM

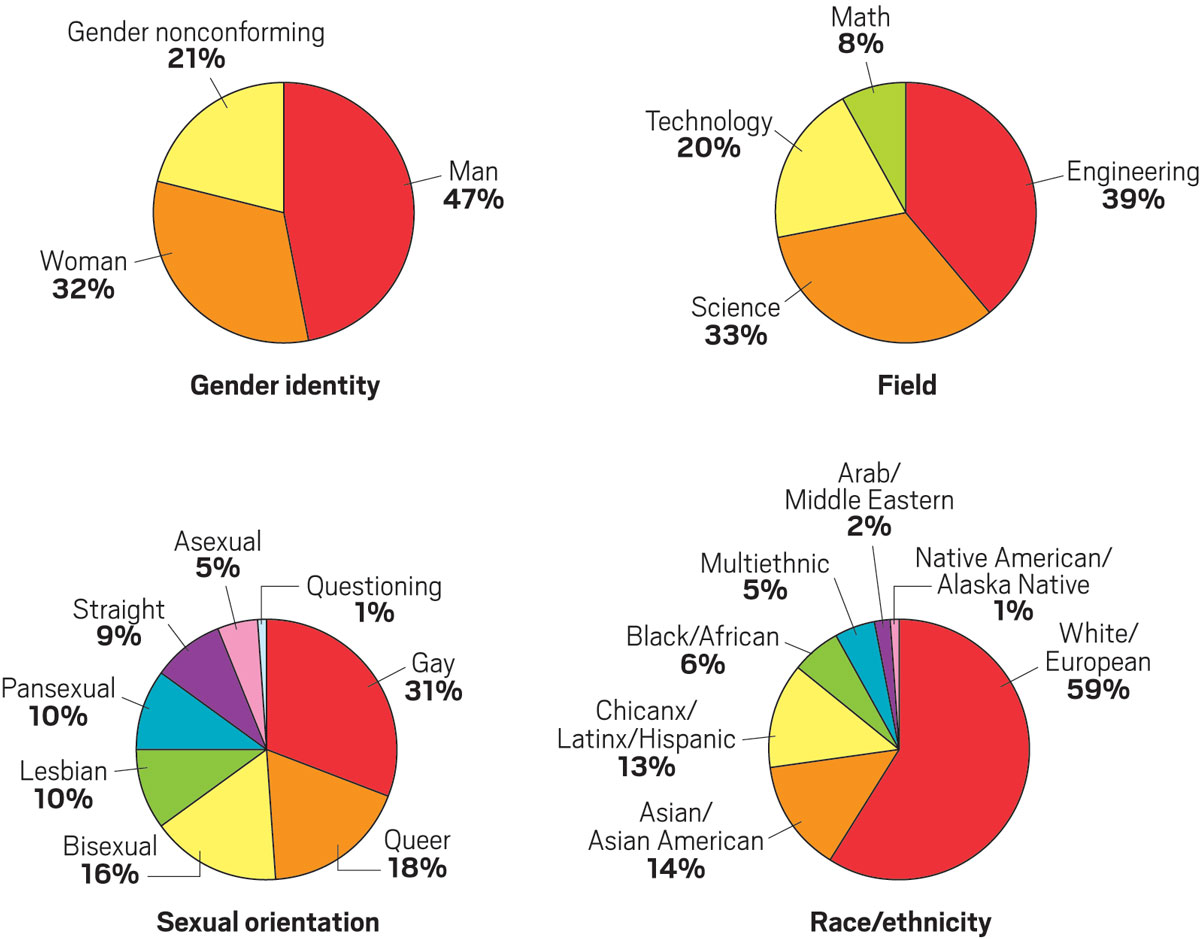

Source: Out in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Note: Percentages are out of about 700 attendees.

Opening up

Knezz didn’t always talk about her identity in the classroom. After a year of teaching introductory chemistry and reading the literature on creating an inclusive classroom, she decided to take the plunge.

Many students in their first year of college are wondering, “What is science, and who am I in this context?” she says. The time is right to make them feel welcome. “I feel like I have to actively combat the weed-out effect,” she says. And it’s not just about keeping students in chemistry—it’s about helping them come out and be themselves. It’s about providing a kind of support that Knezz didn’t have and knows would have been helpful. “I was closeted for a long time, even to myself,” she says. “If I had seen someone either in high school or college who was a role model who was out, maybe I could have known myself better earlier on.”

Trenshaw has similar motivations for coming out to students. “I didn’t have any LGBTQ+ mentors,” he says. “I try to be really out because I didn’t have that, and that would have been really nice.”

Knezz has mentioned her LGBTQ+ identity in about six classes so far and still gets nervous every time, she says. The first time was the hardest. “It felt like I was relinquishing authority,” she says. “But the more I teach, the more I realize the power structure is safe.”

Like Knezz, Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano also comes out to his classes during the first session. He mainly teaches organic chemistry. “People respond to authenticity, to someone being real,” he says. And like Knezz, he also tries not to make a big deal out of it, bringing it up in a list of personal details, including his cat’s name (Khaleesi) and where he grew up (Puerto Rico).

Advertisement

Both have had students visit during office hours to talk about personal problems or to come out to them, and sometimes there are tears. “Teaching students chemistry and also how to love themselves is an added burden I’m putting on my plate,” Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano says. It’s one he’s happy to take on. Just because a professor is queer, however, doesn’t mean they are eager to counsel students. For those who are more private, Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano suggests learning about campus resources such as the counseling and LGBTQ+ centers and referring students there.

Trenshaw, who trains teaching assistants for science classes, says educators should also be aware that other students in the class can create a hostile environment. Educators should be prepared to prevent this from happening and to react appropriately when it does. Little things can make a big difference: Teaching assistants and other teachers can assign students to working groups instead of letting them choose their own. Self-chosen groups can end up excluding students who are different—whether it’s because of race, sexual orientation, or something else.

Education experts recommend keeping gender identity in mind, too. Teachers should give students an opportunity to provide their preferred names and pronouns. Students who are trans, for example, may not be out to their parents and may be enrolled under their given name, not their chosen one. Being misgendered in the classroom or seeing the wrong name on a test can be very painful and set back students’ learning and performance.

All professors, no matter how they identify, should be ready to provide these sorts of resources and support, Hughes says. Many campuses train faculty about what to do when students come out.

Cruz-Ramírez de Arellano says queer teachers and allies alike should be explicit about diversity. No matter their own identity, professors should make sure all students feel welcome in the classroom from day 1. “Tell them that it’s an inclusive classroom,” he says. All science teachers should tell students, “Science needs you, and it needs your unique perspectives.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter