Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Food Science

Newscripts

Creatures of the deep getting high

by Sam Lemonick

October 14, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 41

Lobster pot

The spread of legal marijuana in the U.S. has set off a wave of weed-infused foods that goes far beyond pot brownies. Now teas, beers, snack foods, candies, and even deli meats can get you high. But the latest intersection of cannabis and comestibles isn’t for the diner’s pleasure; it’s out of consideration for the lobster.

Whatever their destination—a lobster roll or surf and turf—all lobsters meet their end by being boiled alive shortly before they’re served, a process meant to impede bacteria that cause food poisoning. Charlotte Gill, owner of Charlotte’s Legendary Lobster Pound in Maine, thinks the whole thing would be better if the lobsters got stoned first.

“If we’re going to take a life we have a responsibility to do it as humanely as possible,” Gill told the Portland Press Herald.

She and her staff experimented with bubbling weed smoke into a lobster tank. Gill reported that after a few minutes the lobster was noticeably more docile and made no attempt to pinch her when she touched him. (The lobster, named Roscoe, was later returned to the sea.)

That sounds nice, but scientists aren’t sure if lobsters experience pain, at least not in the way humans do. Research shows they react to painful stimuli like acid on their antennae or having a claw removed, but that’s different from knowing they suffer in boiling water.

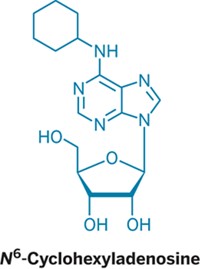

Research does, however, tell us that lobsters respond to cannabinoids, the active ingredient in marijuana. One study found different cannabinoids can excite and depress nerve signals in lobster leg muscles (Neuropharmacology 1988, DOI: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90083-4). Still, “how that relates to pain or behavior—I think we’re a long way from that understanding,” Richard Wahle, zoologist and director of the Lobster Institute at the University of Maine, tells Newscripts.

Regardless, the buzzkills at Maine’s Department of Health & Human Services say Gill can’t serve baked lobsters. A spokesperson told the New York Times that selling lobsters adulterated with marijuana is illegal.

Rolling in the deep

Octopuses, on the other hand, have complex nervous systems. They can use tools and navigate mazes. But even with all those arms, one thing they’re not is cuddly. That is, not until they’ve tried ecstasy.

Gül Dölen of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Eric Edsinger of the Marine Biological Laboratory found that the California two-spot octopus has genetic code for the same nervous system binding sites used by (±)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in humans, even though we’re separated by 500 million years of evolution (Curr. Biol. 2018, DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.061).

Advertisement

MDMA, also called ecstasy or molly, triggers release of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in people. Users report a sense of well-being, heightened empathy, and extroversion. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration recently approved experimental studies investigating MDMA as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Knowing that we share related biological hardware, Dölen wanted to see if ecstasy causes behavioral changes in octopuses, which tend to be solitary animals. She and Edsinger placed a subject octopus in a dilute MDMA solution (the researchers estimated the cephalopods got the equivalent of a low human dose) and then released it into a three-chambered enclosure. To one side was an object to explore, like a Chewbacca figurine. To the other was a second, sober octopus.

Their subjects spent more time with the other octopus and less with the object after they’d been dosed with ecstasy. The researchers also noticed octopuses on MDMA sought more physical contact, extending several tentacles, whereas sober octopuses tended to touch with just one.

And it wasn’t just touch. Dölen says anecdotally she’d never seen octopuses acting like this. On ecstasy “they behaved very similar to what you’d expect in a human,” she tells Newscripts, stretching out their tentacles and swaying back and forth. One got really into the aquarium’s air bubbler. Another spent a while doing backflips.

More seriously, Dölen says octopuses could help researchers better understand what makes other drugs, like the hallucinogens LSD and psilocybin, work. Those drugs have shown promise in treating addiction and helping people cope with death. Octopuses could help scientists adapt recreational drugs to serve medical needs, she says.

Sam Lemonick wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter