Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Persistent Pollutants

Protective gear could expose firefighters to PFAS

Fluorinated compounds in water-resistant textiles break down over time, contacting the skin and shedding into the environment

by Raleigh McElvery, special to C&EN

July 1, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 26

Firefighters face dangers beyond the blaze itself. Their work subjects them to carcinogens from burning materials, as well as toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from flame-suppressing foams. A new study finds that firefighters can also be exposed to PFAS over time through another source: their protective clothing (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00410).

Firefighters suffer from disproportionately high rates of cancer, including types that have been linked to PFAS exposure such as testicular cancer, prostate cancer, mesothelioma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The clothing worn by firefighters, known as turnout gear, is made with fluoropolymer textiles and treated with PFAS for water resistance so that the material does not become soaked and heavy during use.

Graham F. Peaslee, a chemical physicist at the University of Notre Dame, began the study in 2017 when he was contacted by Diane Cotter. Her husband, a 28-year veteran of the Worcester (Massachusetts) Fire Department, had been diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer. Cotter had examined her husband’s gear and found that, while it appeared outwardly intact, there was serious fabric decay on the inside. Cotter wondered whether the uniform could be shedding toxic chemicals and asked Peaslee to take a look.

Peaslee uses nuclear techniques like particle-induced gamma-ray emission spectroscopy to measure the levels of fluorine in various consumer goods—from fast food wrappers to underwear. Based on fluorine levels, he can gauge the amount of PFAS present.

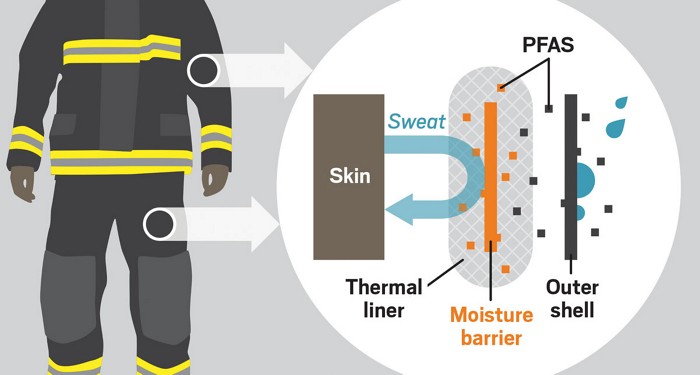

Cotter helped Peaslee collect more than 30 used and unused sets of turnout gear. Each set is made of an insulating cloth thermal layer with a moisture barrier at its center. The gear is coated on the outside with a water-resistant shell. Peaslee’s team found that the shell averaged just over 2% fluorine by weight, while the moisture barrier averaged more than 30% fluorine. Turnout gear, he says, contains “the most highly fluorinated textiles I’ve ever seen.”

Over time, as the layers rub against each other, PFAS from the moisture barrier and the outer shell appear to migrate to the thermal layer, which is PFAS-free when new but accumulates PFAS with time. PFAS may contact the skin via this layer, Peaslee says.

There could also be other routes of exposure, the researchers found. PFAS from the outer shell readily came off in the researchers’ hands as they manipulated the textiles, raising concerns that the chemicals could be accidentally ingested or inhaled. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of samples from the outer layer indicated that its fluoropolymers decompose into other PFAS, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or C8, notorious for polluting water supplies around the world. A single fluorine-laden dust sample collected from a textile storage area supported the idea that the chemicals were dispersing into the environment.

David Q. Andrews, a senior scientist at the Environmental Working Group who has studied the PFAS content of fast food wrappers with Peaslee but was not involved in this work, wonders what additional dust samples from storage areas could reveal about the amount of PFAS shed from turnout gear. PFAS are used in a range of consumer products, from upholstery to athletic wear, and he’s curious whether such treatments release similar amounts into the environment. The health implications of such material loss, he says, likely extend far beyond firefighting uniforms.

Manufacturers of firefighting gear in the US aren’t required to disclose the chemicals in their products, although some are slowly shifting towards PFAS-free options. “Industry has to do the right thing and provide safe alternatives,” Cotter urges.

“It’s a David and Goliath story in that sense,” Peaslee adds. He’s already studying whether these chemicals are absorbed through the skin, and he hopes that others will begin large-scale experiments to probe the long-term health impacts.

“Firefighters are out there risking their lives for us,” he says. “The least we can do is give them the safest gear possible.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter