Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Sustainability

Chemical makers sign up for sustainability-linked loans

Companies are set to save on loan payments if they hit environmental targets

by Alex Scott

June 23, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 25

The global climate crisis is triggering a shift in the way some banks lend money to chemical firms. Bankers are starting to give preferential borrowing rates to companies with good environmental performance. This is not happening because banks are moved by images of starving polar bears or news about deforestation and extreme weather. Instead, their calculations show that borrowers’ improving environmental performance equals less financial risk.

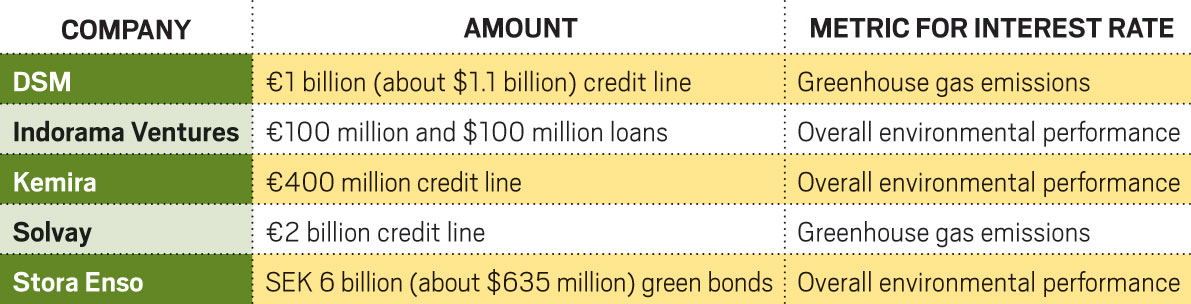

Financiers have picked out the specialty chemical firm Kemira as one of the early qualifiers. In a deal brokered earlier this year, the Finnish company stands to save millions of euros on €400 million (about $450 million) in revolving credit. Kemira is not alone. Over the past year, Stora Enso, Indorama Ventures, DSM, and Solvay became some of the first industrial companies to take sustainability-linked loans in what experts say is an approach that is set to become the norm.

Such a shift in banking practices could also create losers. Chemical companies that fail to meet agreed targets will be hit with a loan-rate rise. And signs are emerging that companies failing to meet international goals for sustainability, such as United Nations targets for greenhouse gas emissions, could be refused loans.

Companies seeking cheaper loans first have to convince banks that they are lower risk. To secure its savings, Kemira had to agree to meet three criteria: reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2020 from a baseline year of 2012, ensure that at least half its revenue is from products that improve customers’ resource-use efficiency, and maintain its gold-standard sustainability rating, which it achieved with a 2018 score of 75 out of 100 from the environmental assessment firm EcoVadis.

“This is a win-win for Kemira and our financiers. We get access to a discount if we meet all our sustainability targets, and the banks in the long run get a lower risk profile for their investment,” says Petri Castrén, Kemira’s chief financial officer. The European banks involved in the Kemira loan deal include Danske Bank, BNP Paribas, and Swedbank.

Early indications at Kemira show that the benefits of taking a sustainability-linked loan are more than financial. The Finnish company is becoming more proactive in the way it develops sustainable innovations, claims Rasmus Valanko, the firm’s director of corporate responsibility. This has benefits for Kemira’s brand and customers, he says.

The Kemira deal came together after the firm’s finance executives heard how the Finnish paper-and-chemical company Stora Enso raised 6 billion Swedish kronor (over $600 million) in 2019 from green bonds. Unlike money from a loan, money raised from green bonds must be spent on sustainable projects. In Stora Enso’s case, the firm is spending the money to acquire a share of the Swedish forestry firm Bergvik Skog.

The Science Based Targets initiative has assessed and approved Stora Enso’s plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Recognition by the consortium of nonprofits is considered a seal of approval that a company’s projected emission cuts are in line with keeping the global temperature increase below 2 °C compared with preindustrial levels.

Interest in environmental, social, and governmental issues and general awareness of sustainability topics are growing among investors, according to Stora Enso. “We want to respond to investor demand and participate in developing the financial markets,” says Pasi Kyckling, the firm’s senior vice president for group treasury.

More such deals are in the cards, according to David McClintock, marketing director for EcoVadis, the company that undertook Kemira’s sustainability assessment. “It could take a while to get momentum, but I think this is just the beginning of chemical companies linking loans to sustainability,” he says.

EcoVadis gives the companies it assesses a final score based on four key areas: environment, labor, anticompetitiveness and ethics, and supply chain. It rates firms in the four sectors out of 100, giving extra weight to environmental parameters.

EcoVadis tracks a company’s sustainability performance reactively from responses to surveys but also proactively by trawling for company information from local news outlets, social media, and reports from nongovernment organizations. The lending banks can then adjust the interest rate according to these findings.

Green trailblazers

To complement its tracking service, EcoVadis recently teamed up more formally with the Dutch bank ING to offer sustainability-linked loans across sectors including construction and shipping but excluding coal because of the sector’s adverse impact on the global climate. For example, in April, ING granted a $100 million sustainability-linked loan to the Russian iron-ore mining company Metalloinvest.

The sustainability score by EcoVadis will determine the initial interest rate on a company’s loan; if the score later goes down, the rate will rise, says Roland Mees, director of sustainable finance for ING.

ING could offer a company with ambitions to markedly improve its sustainability performance an interest rate saving of about 0.1%. “There is a lot of liquidity in financial markets, so interest rates are already low. Even so, we are prepared to go further,” Mees says.

More than 20 chemical companies already use EcoVadis to assess their sustainability performance and that of over 10,000 of their trading partners. McClintock is hopeful that companies from this group—which includes BASF, Bayer, DuPont, Eastman Chemical, and Merck KGaA—may seek to use their ratings to secure preferential loans.

Although most chemical companies that have adopted ecoloans so far are European, the approach could easily be applied in Asia—and especially in China and Southeast Asia, where sustainability in the supply chain is an important issue, McClintock says.

Indeed, in April, Bangkok-based Indorama Ventures secured a loan for both $100 million and €100 million from Japan’s Mizuho Bank at a rate that is 0.25–0.50% below the bank’s standard rate. That rate depends on the firm’s maintaining its environmental, governance, and social performance. This will save Indorama up to about $1 million in annual interest payments, with a further $100,000 savings if its performance improves.

Indorama claims to be the first Thai company to take up a sustainability-linked loan, but it may not be the last. The country has set an ambitious goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 20% over the next decade. Hitting this target will require a range of actions, including innovative technologies and green financing.

In addition to financial benefits, Indorama expects its ecoloan to act as a booster to its corporate culture. “Interest rate savings may not impact profitability significantly; however, the loan brings a discipline and motivation across the whole organization to maintain or better our environmental, social, and governance scores,” says Richard Jones, senior vice president for sustainability at Indorama.

Industry experts say the downsides to sustainability-linked loans are limited. “The only downsides are the chance that the company misses its sustainability targets and incurs higher interest than on a ‘vanilla’ debt instrument,” says Sebastian Bray, head of chemicals research for the German investment bank Berenberg. “Or—in cynical terms—that the direct cost of meeting sustainability targets, such as by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, proves to be greater than the interest rate saving made.”

There could be instances where sustainability-linked loans just don’t suit a company, points out Paul Hodges, chair of the London-based consulting firm International eChem. “It’s a bit like personal finance—the headline rate may look good, but then you realize it could cut across something else you are doing or might want to do,” Hodges says.

Still, companies are jumping in after doing their homework. In May 2018, DSM secured a €1 billion revolving credit facility from a consortium of 15 banks with an interest rate linked to its performance in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. DSM is targeting a 30% cut in emissions by 2030 compared with 2016. To meet the requirements of the loan, DSM also has to show improvements in production efficiency, use of energy, and the share of electricity it draws from renewable resources, says Bruné Singh, the firm’s vice president of group treasury.

Solvay has a similar green finance strategy. In January, the Brussels-based firm took out a €2 billion revolving credit facility with a syndicate of nine banks; the cost of credit is linked to its environmental performance. To achieve a rate reduction, Solvay must reduce the intensity of its greenhouse gas emissions per euro of pretax profit by 40% by 2025 compared with its performance in 2014.

As companies line up to cut their borrowing rates, it is also possible that firms with poor environmental track records may be unable to secure loans from some banks. Italy’s central bank is moving toward such a policy. It aims to encourage lending to companies that are on a sustainable trajectory and discourage lending to those that fail to adhere to UN principles on human rights, labor, and the environment.

“The financial sector, central banks, and supervisory authorities cannot stand in for those who make the policies necessary to decarbonize our energy systems, but they can play an important role in promoting this process,” Ignazio Visco, governor of the Bank of Italy, said in a speech in Rome in May.

The finance sector has woken up to the opportunities and risks posed by corporate environmental performance. Along with regulatory pressure and growing consumer demand for sustainable products, the potential for cheaper loans is becoming another reason why chemical companies may wish to set greener policies.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter