Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Electronic Materials

Movers And Shakers

Cabot Microelectronics’ David Li has a plan for surviving in electronic materials

CEO says the purchase of KMG was a first step to staying independent in a consolidating business

by Michael McCoy

December 1, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 47

When David Li joined Cabot Corporation’s microelectronics materials division in 1998, he was 1 of only about 100 employees. And when Cabot spun off the business 2 years later into an independent, publicly traded firm called Cabot Microelectronics, its annual sales were less than $200 million.

A lot has changed since then. Last month, Cabot Microelectronics reported sales in its most recent fiscal year that surpassed $1 billion. Its workforce is now about 2,000 strong.

Li, who became CEO of Cabot Microelectronics in early 2015, is responsible for a lot of that growth, thanks in large part to last year’s acquisition of KMG Chemicals for $1.6 billion. The purchase was Li’s first big move—and possibly not his last—to ensure that his firm is a survivor in the rapidly consolidating business of producing materials for the semiconductor industry.

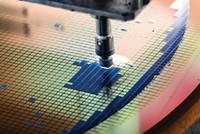

Cabot Corporation, a maker of carbon and silica products, created Cabot Microelectronics in 1995 to pursue the then-nascent business of chemical mechanical planarization, or CMP. In CMP, a dilute slurry of silica and other chemicals is gently applied with a polishing pad to a silicon wafer on which computer chips are being built. In a process that some have called high-tech belt sanding, the slurry smooths—or planarizes—the wafer’s circuitry so that subsequent layers of circuits will lie on a flat surface.

After the spin-off in 2000, Cabot Microelectronics’ stock didn’t pop like Krispy Kreme’s, the doughnut maker that went public the same day. But the firm did well in its early years as major chipmakers like IBM and Intel adopted the CMP technique.

Then came the financial crisis of 2008, which arrested growth, and the company struggled to regain momentum in the following years. When Li became CEO, he vowed to restore forward movement, starting with what he saw as an overly conservative corporate culture.

Cabot Microelectronics at a glance

▸ Headquarters: Aurora, Illinois

▸ Businesses (% of sales): CMP slurries (44%); high-purity electronic chemicals (27%); performance materials, including pipe drag-reducing agents (20%); and CMP pads (9%)

▸ Sales: $1.0 billion

▸ Net earnings: $39 million

▸ R&D spending: $52 million

▸ Employees: ~2,000

Source: Company. Note: Figures are for fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2019, except for R&D spending, which is for the prior fiscal year.

“We’re really a group of engineers,” says Li, himself a chemical engineer, “and I mean that in the very best way and the very worst.”

Li streamlined Cabot Microelectronics’ upper management and revamped its structure to instill more agility and encourage what he calls educated risk-taking. And Li made his first acquisition, buying NexPlanar for $142 million in October 2015. The Oregon-based firm made thermoset polyurethane CMP polishing pads that complemented the thermoplastic polyurethane pads Cabot Microelectronics had developed.

NexPlanar helped catalyze growth in Cabot Microelectronics’ polishing pad business, Li says. Today, Cabot Microelectronics is the world’s number 2 in CMP polishing pads, after DuPont, and the world leader in slurries. The purchase got him thinking about a more transformative deal.

Cabot Microelectronics’ customers are firms like Intel, Samsung, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which dominate the semiconductor industry with their ability to make huge investments. Li and his team decided that size is equally important for suppliers like theirs. “We thought there’s a benefit to consolidation and that we should be doing the consolidating,” Li says.

So when KMG became available, Li pounced. But unlike the NexPlanar acquisition, which was a comfortable move in a market the firm knew well, KMG was a step outside its comfort zone.

KMG’s main business was making high-purity chemicals and blends used to clean circuit-covered wafers between fabrication steps. One example of such a blend is SC1, a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and ammonium hydroxide that removes organic matter and other particles. High-purity acids, bases, and solvents are used in other cleaning steps.

Li says he’s happy with how the two companies fit. Customers use KMG’s chemicals to clean wafers after CMP and other chip fabrication steps, such as etching and photoresist developing. “With KMG we are supplying materials to almost every process step in semiconductor fabrication, which gives us great insights into what our customers are doing,” he says.

David Silver, an equity research analyst who covers Cabot Microelectronics for C.L. King & Associates, agrees that the purchase was a smart move. It’s true, he says, that KMG’s cleaning chemicals aren’t as high tech as Cabot Microelectronics’ CMP slurries and pads. Yet, overall the acquisition is helping Cabot Microelectronics become more critical to its semiconductor industry customers and touch more parts of their production processes.

While the deal made good strategic sense, Silver says it was likely defensive as well. He points out that Li has watched competitors get swept up by consolidation in the electronic materials industry and may have acted to keep from being next. “Could Cabot have remained independent if they didn’t make the move?” Silver asks.

The consolidation has been sweeping. In 2013, Merck KGaA spent $2.6 billion for AZ Electronic Materials, a producer of dielectrics, CMP slurries, and photoresists. A year later, Entegris agreed to buy the electronic chemical maker ATMI in a deal worth $1.2 billion. And the merger of Dow and DuPont combined two electronic materials businesses into what is now DuPont.

The trend continued after Li struck his deal for KMG in 2018. Entegris kicked off a minidrama in January of this year when it signed an agreement to merge with Versum Materials, a maker of deposition materials, specialty gases, and CMP slurries.

Soon after, Merck KGaA stepped in with what it said was a better, $6 billion offer to acquire Versum outright. After a few weeks of saber-rattling and pot sweetening, Merck prevailed: in early April, Versum agreed to be bought. Entegris walked away with a $140 million breakup fee, money that helped it buy two smaller electronic materials firms—Digital Specialty Chemicals and MPD Chemicals—in the spring and summer.

Are more deals to come? Silver thinks so. “If you look around, you still see a lot of products and services offered by small private companies or small divisions of large multinationals,” he says.

Li says he’s keeping an eye out, but unlike Silver, he doesn’t see a landscape brimming with opportunity. Many Asian competitors, for example, “are more regionally focused and running a low-cost business model, which is not our strategy,” Li says. Several Japanese firms are important players in high-end materials like photoresists but have little history of being acquired by Western competitors.

Li cautions that any additional deals must help Cabot Microelectronics meet its own ambitious financial goals, which include raising its ratio of operating earnings to sales to 35% from about 31% today. “If you think about adding that challenge, the high-quality opportunities become more limited,” he says.

Even without another acquisition, Li wants to increase Cabot Microelectronics’ annual sales by 50% over the next 5 years, to about $1.5 billion. And he’s confident of hitting that goal because of the fundamental strength of the semiconductor industry.

It’s not doing great at the moment, Li admits. In August, World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, an industry group, forecast that chip sales would be down more than 13% this year. In the quarter that ended Sept. 30, Cabot Microelectronics’ CMP slurry sales were down 7.7% from the year-earlier quarter, although pad and cleaning chemical sales were up 1.8 and 1.5%, respectively.

Interestingly, Cabot Microelectronics’ gold star segment in the quarter was performance materials, a business that came with KMG. The standout there was a line of drag-reducing agents that pipeline operators are increasingly adding to push more oil through their pipelines without having to increase capacity.

Speaking to stock analysts about electronic materials on the company’s quarterly conference call, Li said the semiconductor industry got ahead of itself and built up too much supply. But he said he’s bullish about the long term, noting that more chips will be needed “to support emerging applications such as internet of things, autonomous driving, virtual reality, and high-performance computing.”

He also pointed to a growing need for Cabot Microelectronics’ CMP products as semiconductor makers shrink circuit lines to 7 nm and, soon, 5 nm widths in the most advanced logic chips and stack 100 or more layers of circuitry in high-end memory chips.

Silver at C.L. King wonders if the chip industry’s adoption of extreme ultraviolet light–based lithography for the latest logic chips might actually cut into demand for CMP products. Before extreme ultraviolet light (EUV) lithography, the prevailing deep UV method couldn’t create the smallest circuit lines in one pass, so chipmakers resorted to a CMP-intensive process called multiple patterning to draw them.

Li claims to be unconcerned, saying he expects a “negligible” reduction in planarization as EUV is adopted. Moreover, he says, technology advancement is positive for everyone involved in chip manufacturing. “EUV is needed to continue to advance the technology,” Li says. “If technology advancement stops, that’s not good for us.”

His view is that Cabot Microelectronics has become one of just a handful of firms with the size, breadth, and research capabilities to serve an industry with ever-advancing technology needs and quality standards that are more stringent than any drug company’s or automaker’s. “You cannot be a start-up and support a Samsung or a TSMC,” he says. “These requirements drive out the weaker players, and the stronger players are left.”

Today, Li says, Cabot Microelectronics is one of those stronger players. The culling may not be over, but when it is, Li wants his firm to be among the ones left standing.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter