Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Polymers

The chemical industry is bracing for a nylon 6,6 shortage

Misfortune has befallen polymer manufacturers; now users must weigh their options

by Alexander H. Tullo

October 7, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 40

On Aug. 22, 2015, a brand-new adiponitrile plant in the burgeoning Chinese chemical town of Huantai exploded, killing one person. Coming 10 days after an enormous chemical blast in Tianjin, China, that killed more than 170 people, the event was largely overlooked.

But for the nylon 6,6 market, the accident was quite consequential. It took a plant making a key raw material out of commission, marking the start of a period of supply tightness that has been getting worse. Other, more established producers of nylon 6,6 and its raw materials have since suffered their own outages. Prices have spiked. Now some observers see an outright shortage ahead.

Nylon 6,6 users may resort to switching to competing engineering polymers to make automotive and industrial parts. Makers of such polymers—nylon 6 and high-end plastics like polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) and polyphthalamide—see an opportunity to poach business. Meanwhile, nylon 6,6 makers are trying to soothe concerns and head off customer defections by promising new capacity.

When it was introduced in 1940 as an alternative to silk, nylon 6,6 was considered a fiber material. Today, fibers represent only about a third of its use. Most nylon 6,6 is injection molded into tough plastic parts. The majority goes into auto applications such as air intake manifolds, electrical components, and oil pans.

“Nylon 6,6 is particularly well suited for these kinds of applications because it is resistant to heat and also to oil and grease,” says Brendan Dooley, director of engineering plastics in North Americaat the consulting firm IHS Markit. Other markets for nylon 6,6 include industrial applications, power tools, and cable ties.

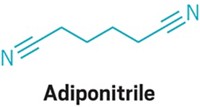

Nylon 6,6 is made via the polycondensation of adipic acid and hexamethylenediamine (HMD). Adipic acid is synthesized in a two-step process that begins with cyclohexane. HMD is obtained by hydrogenating adiponitrile.

A half-dozen or so companies across the globe make nylon 6,6 polymer and adipic acid. Adiponitrile has always been a bottleneck for the nylon 6,6 business because only three firms—Ascend Performance Materials, Invista, and Butachimie—make the chemical at large scale. And Butachimie is itself a French joint venture between Invista and Solvay.

The barriers to entering the adiponitrile business are high, Ascend CEO Phil McDivitt says. “Adiponitrile is very technologically challenging to make” and requires significant capital investment, he says.

Invista and Butachimie produce adiponitrile by reacting butadiene with hydrogen cyanide, a process developed by Invista’s forerunner, DuPont. Ascend uses a Monsanto-invented electrochemical process that starts with acrylonitrile.

With the world economy recession-free for a decade now and car production booming, demand for nylon 6,6 has been strong. Dooley expects the market—2.1 million metric tons per year today—to grow by 2.7% annually over the next five years.

The trouble for the nylon industry is that production hasn’t been keeping up. “Demand is growing at the same time there is a structural shortage in feedstocks that are used to produce nylon 6,6, most notably adiponitrile,” Dooley says.

The facility that exploded in 2015 was built by Shandong Runxing New Material to become a fourth major producer of adiponitrile. At the time of the incident, the plant had 100,000 metric tons per year of annual capacity, less than its rivals. Shandong Runxing planned to gradually expand it to 300,000 metric tons, about 18% of global capacity. But now, “There is no evidence that plant is going to be rebuilt,” Dooley says.

In addition to the hole in China, the big existing nylon 6,6 players have been hit with one interruption after another—for every reason imaginable—over the last year.

Invista had to declare force majeure for adiponitrile, HMD, adipic acid, and nylon 6,6 last year because Tropical Storm Harvey interrupted operations at its Texas plants.

At Butachimie, a labor dispute hit production earlier this year. Around the same time, Ineos, which makes HMD on BASF’s behalf in Seal Sands, England, suffered a failure in a steam generation unit. Solvay warned customers in August that low water on the Rhine River, due to a heat wave, crimped its nylon 6,6 activities.

And Ascend lost capacity for several chemicals produced at multiple sites. Harvey affected its acrylonitrile plant in Chocolate Bayou, Texas. In January, freezing weather interrupted adiponitrile and HMD production in Decatur, Ala.

Then in July, a fire took out some of Ascend’s nylon 6,6 polymer capacity in Pensacola, Fla., forcing the company to declare force majeure. “Under normal conditions, this likely would have been a situation that we would have been able to handle,” McDivitt says. But because of the tight market, the company didn’t have the inventory to cushion the blow. “We had a full order book,” he notes.

Prices have been rising all this time. According to IHS Markit’s Dooley, spot prices are now $5.00 per kilogram, $2.00 more than they were a year ago. “Buyers need their material, and they are searching the world for sufficient supplies,” he says.

Customers might be willing to switch to other polymers—at least temporarily. Cliff Watkins, director of applications development at the engineering polymer distributor PolySource, has been sounding the alarm about nylon 6,6. He organized a webinar on the topic in July in which he projected that a 200,000-metric-ton shortfall of nylon 6,6 output today could grow to 800,000 metric tons by 2021.

Watkins outlined possible substitutes. The most obvious candidate is nylon 6, which is normally less expensive than nylon 6,6 and is much cheaper now. Boasting of the potential for new business, Erin Kane, CEO of nylon 6 maker AdvanSix, told analysts in August that 15–20% of nylon 6,6 applications are attainable with nylon 6.

That estimate sounds reasonable to Watkins. For some applications, users might have known they could switch but didn’t because of the time and investment required to reengineer parts and get customers to approve them, he says. Higher nylon 6,6 prices and lower availability are making them reconsider. “This is the time to go back to your customer and ask them if they really need nylon 6,6,” he says.

The answer isn’t simple, because nylon 6 won’t work for everything. Nylon 6,6 starts to deform at 260 °C; nylon 6, at 220 °C. Nylon 6,6 also has better chemical resistance as well as less of a tendency to absorb moisture and expand. For instance, nylon 6 might not work in cable ties, which have to secure wires tightly in environments like damp basements.

Nevertheless, “There are a lot of applications where people are ready to look at nylon 6,” says Sanjay Jain, business director for polyamides and PBT at nylon 6 maker DSM. For auto parts such as brackets and frames, which might not need nylon 6,6’s most exclusive properties, he expects to see conversion start over the next few months.

Where nylon 6 might not cut it, Jain says, nylon 6,6 customers can opt for higher-end polymers. DSM makes nylon 4,6 and 4,10 and polyphthalamide, which match nylon 6,6 in heat and chemical resistance.

Another potential substitute, Watkins says, is PBT, which beats nylon 6,6 in resisting water absorptionbut falls short in toughness. Another alternative that might outperform nylon 6,6 is aliphatic polyketones, which PolySource has been distributing for the South Korean chemical maker Hyosung.

“But there is a cost penalty,” Watkins admits, adding that exotic nylons such as 4,6; 4,10; or 6,10are also more expensive than nylon 6,6. But parts makers “may not have a choice” if they can’t get material at all, he says.

The big nylon 6,6 producers say switching might be rash. “I wouldn’t advise market participants to make long-term decisions based on short-term supply tightness,” says Bill Greenfield, president of Invista Intermediates.

Ascend’s McDivitt says he’s seen churn in the engineering polymer business for many years: Nylon 6 takes business away from nylon 6,6, and nylon 6,6 filches applications from metals and more expensive polymers. But he hasn’t seen a rush to other materials specifically because of the supply situation. “So far, from our experience, we haven’t seen any substitution in our 6,6 business with 6,” he says.

And suppliers promise the cavalry is charging in with capacity. “I think it’s valuable to note that those of us who know the nylon 6,6 market most closely are willing to invest,” Greenfield says.

Invista has projects to upgrade technology at two adiponitrile plants—a $250 million investment at its plant in Victoria, Texas, coming on-line in 2020 and another investment at its joint venture in France for 2019. Invista’s Orange, Texas, adiponitrile plant already has the new technology, which promises to improve yields and lower energy consumption. The new technology is adding more than 200,000 metric tons per year of capacity.

Additionally, Invista says it will spend $1 billion to build a new 300,000-metric-ton adiponitrile plant in China by 2023. Nearer term, the company is adding 40,000 metric tons per year of nylon 6,6 capacity at its plant in Shanghai by 2020.

Ascend is also expanding capacity by 10–15% across the board for adiponitrile, HMD, adipic acid, and nylon 6,6. In May, amid growing market worry, the company announced it had expanded adiponitrile capacity by 50,000 metric tons in 2017, is adding 40,000 metric tons by the end of this year, and will expand by another 180,000 metric tons by 2022.

Advertisement

IHS Markit’s Dooley thinks the investments will make a difference. “It’s a little bit late, but on the other hand, it’s coming,” he says. “If we can make our way through 2019, by 2020 we will begin to see the edge come off the market.”

CORRECTION:

This story was updated on Oct. 17, 2018, to correct the location of the Shandong Runxing New Material adiponitrile facility. It was in Huantai, not Yantai, China.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter