Vaccines

mRNA vaccines took center stage

The pandemic pressure cooker puts the hyped technology to the ultimate test

by Ryan Cross

A year ago, you wouldn’t have expected your friends and neighbors to be asking you for the latest gossip about messenger RNA. The nascent technology, which can be used as either therapy or vaccine, was hyped in the biotech industry, but it never loomed large in the public sphere. Fast-forward to late 2020, and promising data on mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 are making the front pages of every major news outlet.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put mRNA vaccines in the spotlight and likely shaved years off the technology’s development. At the beginning of 2020, the mRNA company Moderna had enrolled only about 1,500 people across its many clinical trials. If the vaccines are authorized for use, next year more than 1 billion people could get an mRNA vaccine developed by Moderna or a competing shot jointly developed by Pfizer and the German firm BioNTech.

“I think it would be the best outcome we could have hoped for,” says Michael Haydock, an analyst at Informa Pharma Intelligence. “It is a completely unproven technology, and yet they are the two vaccines that are likely to make it on the market first.”

Never before in biotech history has a new technology debuted with the potential to shape so many people’s lives. The first generation of products based on new technologies—gene therapies, cell therapies, and RNA interference drugs, to name a few—is typically designed to treat rare diseases. That’s because it is usually easier to test a new technology in a small group with a well-defined disease.

mRNA loyalists are hopeful that a successful COVID-19 vaccine will catapult the technology to instant stardom.

“Once the first mRNA vaccine gets licensed, and if it turns out to be safe and effective, then everything will be much, much easier in the future,” says Norbert Pardi, an mRNA vaccine scientist at the University of Pennsylvania. “This will be a huge step forward for the field.”

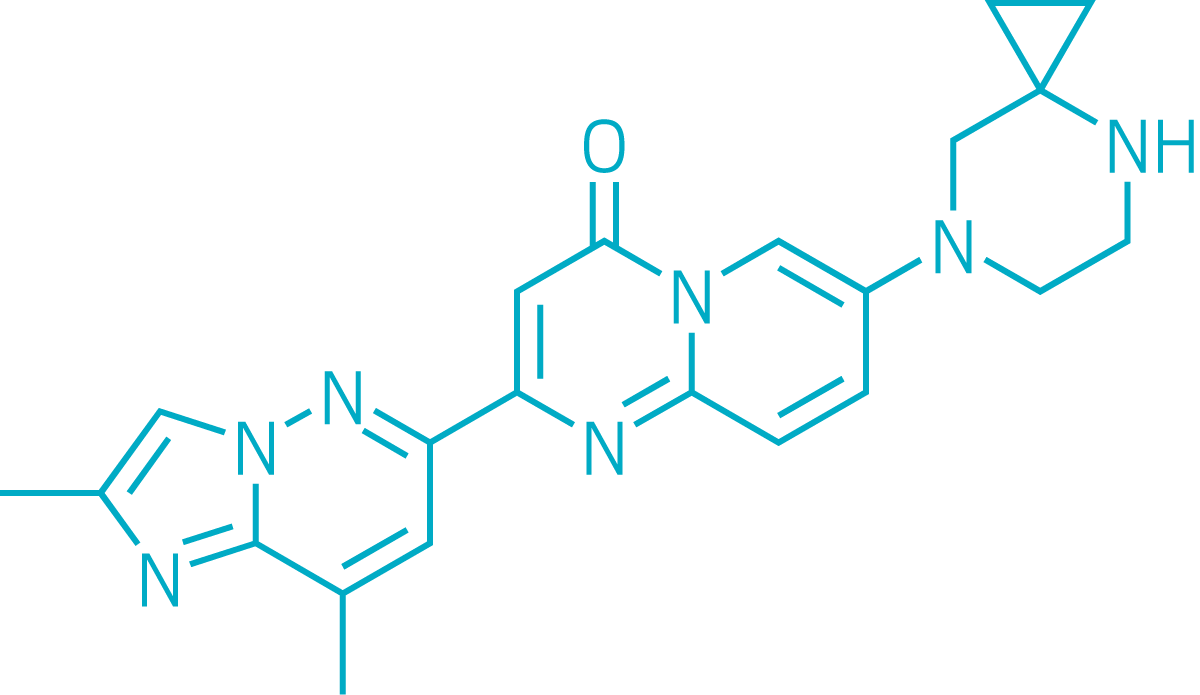

Moderna has long touted mRNA as the ideal technology for rapid vaccine development. To induce immunity, traditional vaccines often use whole viruses or viral proteins, which must be painstakingly grown in vats of cells. mRNA vaccines, in contrast, outsource production of viral proteins to cells in our bodies. Moderna encoded the genetic instructions for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in mRNA strands, which it manufactures synthetically.

In theory, the process is quick and easy. But like any potentially disruptive technology, mRNA has had its doubters. “Until now, many companies didn’t believe that mRNA would have its day,” says Lior Zangi, an associate professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “Now it has lived up to its promise.”

mRNA vaccines aren’t out of the woods yet. Moderna and Pfizer haven’t published full data sets from their trials, leaving many questions about the ultimate impact their vaccines will make on the pandemic. The low temperatures required for their storage could hamper distribution. Scientists warn that we must remain vigilant for rare, but severe, side effects that could potentially arise once millions of people get an mRNA vaccine for the first time. And although the immune responses in the trials looked good, we don’t know how long they will last.

Still, excitement for the potential of mRNA vaccines to slow the pandemic is palpable. “Up until this year, investment in infectious disease vaccines has really been falling behind,” says Michael Kinch, director of the Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology at Washington University in St. Louis. “Hopefully the pandemic will wake the world up.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter