Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Development

The new drugs of 2019

The 48 medicines represent another highly productive year for the pharmaceutical industry, with cancer and rare-disease drugs again dominating the list

by Lisa M. Jarvis

January 17, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 3

Credit: Will Ludwig/C&EN/iStock Photo

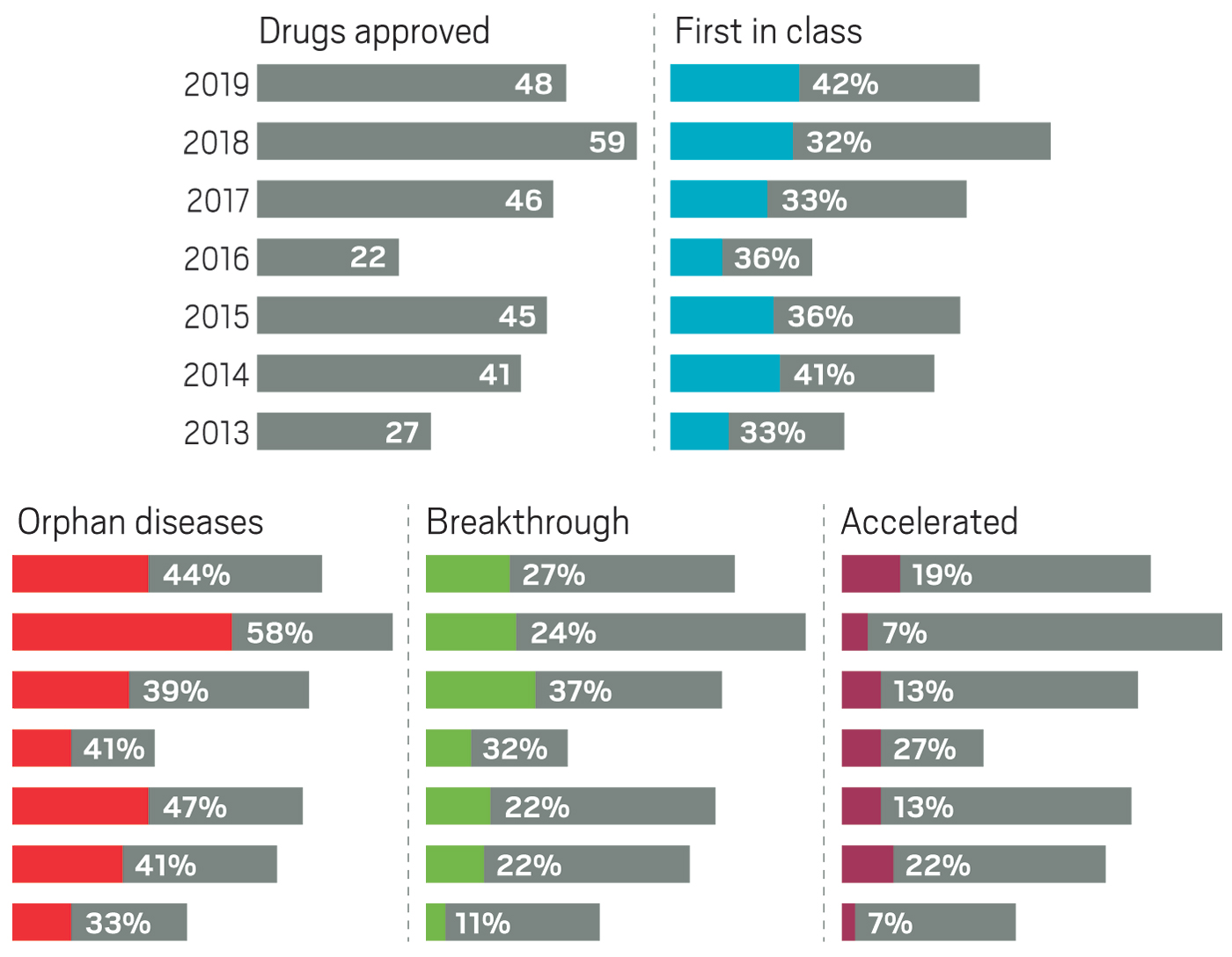

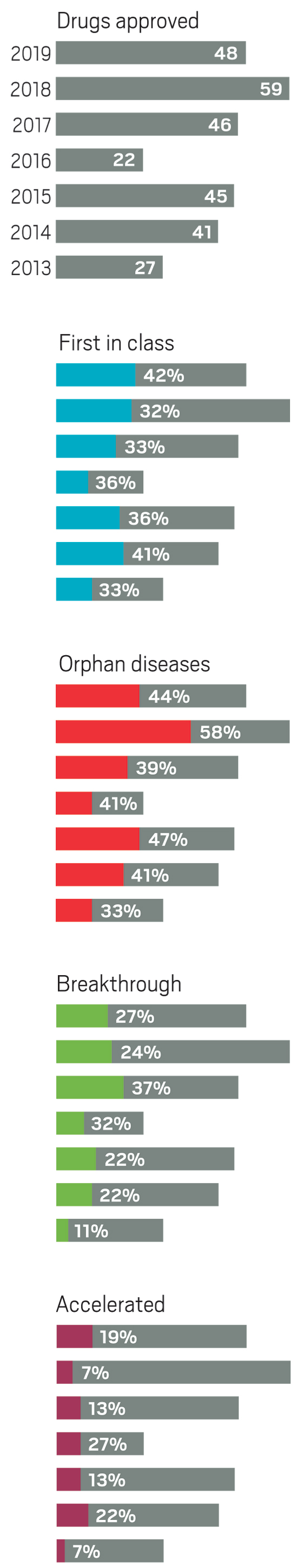

Although pharmaceutical companies last year were unable to top the record-shattering 59 new drugs approved in the US in 2018, they were still on a roll. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration green-lighted 48 medicines, a crop that includes myriad modalities and many new treatments for long-neglected diseases.

2019 new drugs by the numbers

48

New molecular entities approved in 2019

59

New molecular entities approved in 2018

67%

Small molecules

42%

First-in-class drugs

44%

Rare-disease drugs

11

New cancer treatments

6

Products added to Novartis’s portfolio

3

Antibody-drug conjugates

Source: US Food and Drug Administration.

Taken together, the past 3 years of approvals represent drug companies’ most productive period in more than 2 decades. Still, some analysts caution that the steady flow of new medicines could mask troubling indications about the health of the industry.

The year brought several notable trends. The first was an uptick in the number of novel mechanisms on display in the new drugs. Roughly 42% of the medicines were first in class, meaning they had new mechanisms of action; this is a jump over the prior 4 years, when that portion ranged between 32 and 36%. Another trend was the influx of newer modalities. While small molecules continue to account for the lion’s share of new molecular entities (NMEs), making up 67% of overall approvals in 2019, the list also includes several antibody-drug conjugates, an antisense oligonucleotide therapy, and a therapy based on RNA interference (RNAi).

Yet another encouraging trend was the influx of innovative therapies for underserved diseases. Standout approvals include two new drugs for sickle cell anemia (Global Blood Therapeutics’ Oxbryta and Novartis’s Adakveo), an antibiotic for treatment-resistant tuberculosis (Global Alliance for TB Drug Development’s pretomanid), and a therapy for women experiencing postpartum depression (Sage Therapeutics’ Zulresso).

“The quality of the drugs over the last decade or so has steadily improved since the depths of the innovation crisis 10–12 years ago,” says Bernard Munos, a senior fellow at FasterCures, a drug research think tank. “We’re seeing stuff that frankly would have looked like science fiction back then.”

Those futuristic new therapies include Novartis’s Zolgensma, a gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy; Alnylam Pharmaceuticals’ Givlaari, the company’s second marketed RNAi-based therapy; and several critical vaccines for infectious diseases, including Ebola, smallpox, and dengue fever. Not all those edgy therapies appear in C&EN’s list. We track approvals granted through the FDA’s main drug approval arm, the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; drugs like vaccines and gene therapies are generally reviewed through the agency’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The new-approvals list also doesn’t include several therapies that made their way to patients for the first time, even though the FDA doesn’t consider them new drugs. For example, the agency gave its green light to Johnson & Johnson’s Spravato, making it the first new treatment option for people with major depressive disorder in more than 50 years. The drug is the S enantiomer of ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist that had been long approved as an anesthetic, gained notoriety as a club drug, and was used for years off label to treat severe depression (see page 18).

Also notable in 2019 was a slight dip in the number of cancer drugs, which in recent years typically made up more than a quarter of all new medicines. Last year’s 11 cancer treatments accounted for roughly 23% of approvals.

HEALTHY HARVEST

Click here or the image below to view the full interactive table.

Click here to download a pdf table of the new drugs.

Most cancer drugs that did reach the market benefited from one or more special FDA statuses meant to speed the development of important and innovative therapies. For example, in 2019, cancer drugs accounted for seven of the nine NMEs that received “accelerated approval,” a status that allows the agency to OK a drug on the basis of a surrogate end point rather than a clear clinical benefit. In the case of cancer drugs, that means showing a treatment can keep tumors from growing, rather than demonstrating its ability to extend a patient’s life.

That speedier pathway is not without controversy. Last year, a group of pharmacoeconomics researchers at Harvard Medical School published a study in JAMA Internal Medicine showing that just 20% of the cancer drugs that received accelerated approval between 1992 and 2017 actually prolonged survival in trials conducted after the drugs were marketed.

Two of the cancer drugs that received accelerated approval got their OK in December, a month that historically brings a surge in FDA nods. Indeed, although the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research’s busiest 2019 month was August, when nine new drugs were approved, December brought seven NMEs—six of which landed during a stretch of 5 hectic days before the Christmas holiday.

In July, a separate study showed that the FDA often approves 80% more drugs in December than in any other month, a “desk-clearing” process that the authors say could have serious consequences for patients. “Drugs approved in December and at month-ends are associated with significantly more adverse effects, including more hospitalizations, life-threatening incidents, and deaths,” the researchers write.

While some analysts worried about the real-world benefits of newly approved drugs, others parsed the 2019 list to understand the health of big pharma. Of the big firms, Novartis was the most productive, adding six new treatments covering a wide range of diseases and therapeutic modalities, a number that includes the company’s gene therapy Zolgensma. Nearly all the other big companies had just one drug—or in some cases zero drugs—on the list.

That bumper crop also made Novartis the most productive firm over the past decade. It gained 20 new drugs between 2010 and 2019, according to FasterCures’ Munos, who closely tracks biomedical innovation. At the other end of the spectrum are companies like GlaxoSmithKline, which had just 11 new drugs during that period, he says.

Munos notes that major drug companies accounted for 18 of the new treatments approved in 2019. That was a good year. Aside from a crest of 20 new products in 2011, the number has rarely risen above 15 or 16 since 1990. “That trend has been absolutely flat,” he says.

OPEN SPIGOT

What hasn’t been flat is the amount of R&D dollars devoted to developing those drugs, which Munos says has increased by about an 8.5% compounded rate over the past 30 years. “They basically keep on spending more and more for roughly the same output.”

Another way to consider big pharma output is as a proportion of all newly-approved drugs, notes Jamie Munro, executive director of the UK-based health-care research organization Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science. By that measure, big pharma’s contribution has fallen. In 2018, major companies accounted for just 26% of new drugs, the lowest portion of NME launches in a decade. “We’ve seen that trend over a number of years,” Munro adds.

He points to several reasons for the decline. In the past decade, the drug industry has shifted its investment from primary-care treatments, which typically require large, expensive clinical trials that are difficult for small companies to conduct on their own, to specialty-care indications like oncology, for which a drug might be approved on the basis of a much smaller study.

Similarly, the industry has, in the past 5 years, focused more on drugs for rare diseases, which now regularly accounts for at least 40% of new approvals. They are another class in which small companies can successfully bring a drug from idea to market.

With small and medium biotech firms accounting for an increasing percentage of the novel drugs approved each year, big pharma companies are naturally refilling their portfolios by acquiring the most productive of those firms. In 2019, several biotechs that were directly responsible for or had a hand in getting multiple new drugs onto the market were bought. Deals included Eli Lilly and Company’s purchase of Loxo Oncology, Pfizer’s buyout of Array BioPharma, and Roche’s acquisition of Spark Therapeutics.

While big pharma has always used dealmaking to fill its innovation gaps, Michael Kinch, founder and head of Washington University in St. Louis’s Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology, sees a worrisome trend: the number of companies that are directly contributing to the development of approved drugs is shrinking.

Kinch and his colleagues have been meticulously tracking every company, small and large, that has had a hand in the invention or development of a new medicine. His team discovered that of the more than 5,000 organizations that have ever contributed to an approved drug, a hefty chunk have disappeared.

“We’ve lost half of the companies that have contributed to the research and development of a new drug since 2003, due almost entirely to industry consolidation,” Kinch says. “In the long term, our ability to continue introducing new medicines is now fundamentally threatened.”

And since a large chunk of those losses occurred since 2015, it “raises long-term questions about sustainability,” Kinch adds. When he considers whether the industry will continue to be as productive as it has been in the past few years, he says, “Based on what we’re seeing, it’s troubling.”

CORRECTION

This story was updated on Feb. 4, 2020, to correct the classification of Ga-68-DOTATOC. It is a peptide, not a small molecule. Statistics on the share of approvals that are small molecules have been updated accordingly.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter