Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Oncology

The difficult search for the right recipe in cancer immunotherapy

With so many ingredients on hand, can the oncology community figure out how to sensibly and efficiently combine checkpoint inhibitors with other drugs?

by Lisa M. Jarvis

June 1, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 23

Credit: Chris Gash

In the early years of this decade, excitement began to ripple through the cancer community about medicines called PD-1 inhibitors. By blocking proteins that tumors use to slow down the immune system, they were having a powerful effect against some types of cancer. Many oncologists vividly recall their first patient to experience a turnaround after treatment with the new immunotherapy drugs.

In brief

Since 2014, trials pairing checkpoint inhibitors with other drugs have proliferated. The hope is to expand the benefits of immunotherapy, which works remarkably in some, but far from all, cancer patients. Now, following the high-profile failure of a study combining drugs from Merck and Incyte, oncology experts are asking what can be done to improve the odds in immuno-oncology. Read on to learn about the many challenges of harnessing the immune system to combat cancer.

“I see the face, I know the name of the first patient that I had that responded to an anti-PD-1. And that was over six years ago,” says Kim Blackwell, a renowned breast cancer researcher who in March left Duke University Medical Center to lead early-phase development and immuno-oncology at Eli Lilly & Co.

A mountain of data has since emerged to heighten the buzz around checkpoint inhibitors, a class of drugs encompassing PD-1 inhibitors and other molecules that help release the brakes on the immune system. Six checkpoint inhibitors are now approved on the basis of studies showing their ability to shrink many kinds of tumors, including melanoma and some solid tumors. For some people, such as those with a rare, inherited form of cancer called Lynch syndrome, the effect is so dramatic that they can stop treatment. Their cancer simply disappears.

“This was really the first time you could look an adult patient with a solid malignancy in the eye and say, ‘There is a chance that we will cure you,’ ” says Drew Pardoll, director of the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins University. Pardoll contributed to the discovery of key components in the immune checkpoint pathway and the development of several immuno-oncology drugs.

Oncologists would like to be able to utter those words to every person who walks into their offices. But even in the types of cancer where they work well, checkpoint inhibitors help just a slice of patients. Almost as soon as researchers realized that PD-1 inhibitors could become a foundational part of cancer immunotherapy, companies were searching for companion molecules that could boost their effect.

“The field went crazy,” Pardoll says. “There was a sense that the sky was potentially the limit.”

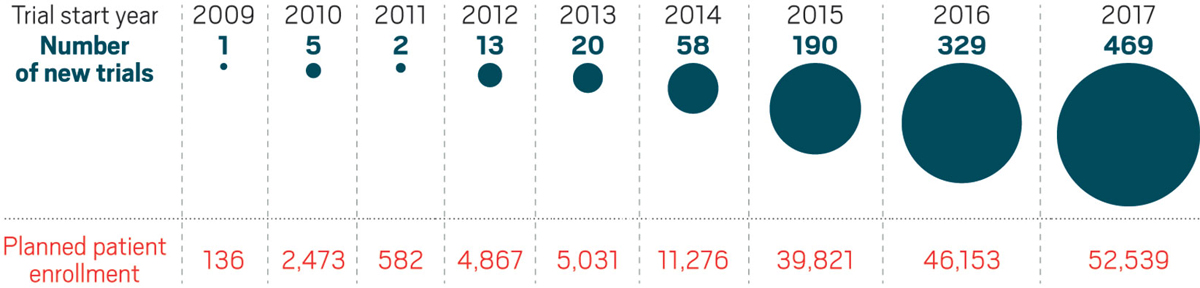

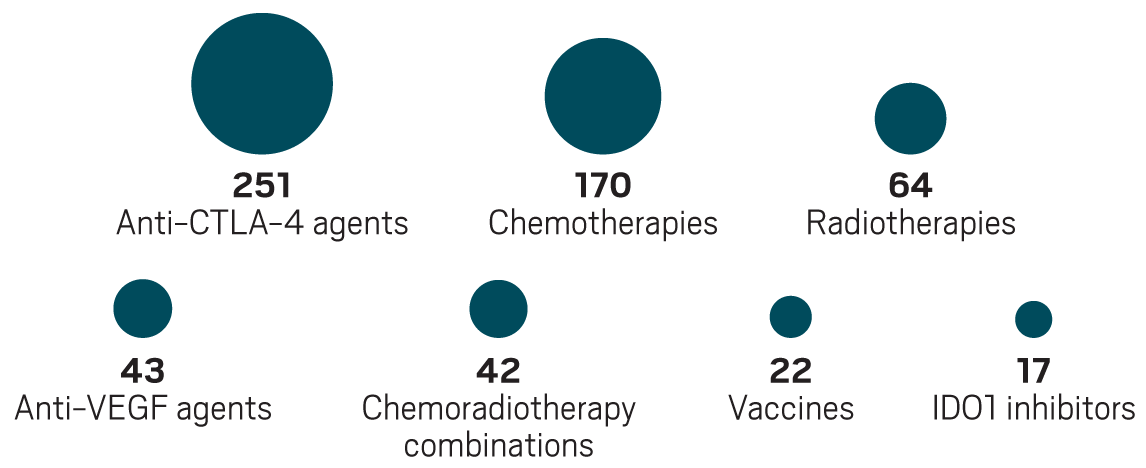

The number of clinical studies combining checkpoint inhibitors with other agents has grown dramatically since 2014.

The number of clinical studies combining checkpoint inhibitors with other agents has grown dramatically since 2014.

The number of clinical studies combining checkpoint inhibitors with other agents has grown dramatically since 2014.

For companies, the incentive to find immunotherapies to combine with checkpoint inhibitors was clear: The two approved PD-1 inhibitors, Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and Opdivo (nivolumab), are expensive. Selling for upward of $150,000 per year, they have amassed billions of dollars in sales for their manufacturers, Merck & Co. and Bristol-Myers Squibb, respectively.

Meanwhile, biotech firms with just minimal evidence that their immunotherapies could enhance the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors have seen stock prices soar. Some small immuno-oncology companies have been acquired for sizable amounts despite offering little data to back up their work.

The gold rush has created an increasingly crowded and complex field. According to the nonprofit Cancer Research Institute, as of last September companies were running human studies of roughly 250 drugs that block or activate molecules expressed by tumor-fighting T cells or that target other immunomodulatory molecules. More than 1,100 clinical trials that combine inhibitors of PD-1 or its ligand PD-L1 with another treatment are under way. Experimental immunotherapies, targeted drugs, or chemotherapies account for the lion’s share of the partners.

But figuring out how to bring immunotherapy’s benefit to more cancer patients is not a trivial task. The field has already been rocked by failures, most notably a large study combining Keytruda with an experimental drug from Incyte. As the number of combination studies mushrooms—by 42% between 2016 and 2017, according to the Cancer Research Institute—researchers are assessing what can be done to improve the odds of success.

Many worry that the high stakes foster drug development decisions that make more big failures inevitable. “The development of pembrolizumab was a home run,” says Jason Luke, an oncologist specializing in immunotherapy at the University of Chicago Medicine. “It may be the greatest drug that was ever developed for cancer.”

At the same time, the drug’s dramatic results meant it went from Phase I clinical trials to the market in less than four years. Although oncologists agree that good drugs should become available to patients as quickly as possible, that fast track creates a conundrum: “Even now, as a community, we don’t understand why anti-PD-1 antibodies like pembrolizumab and nivolumab work,” Luke says. “It doesn’t matter, because they do work, but when you try to do development like that broadly, you’re going to get mistakes.”

IDO implosion

Over the past several years, big pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars collecting hundreds of experimental immuno-oncology drugs that promise to boost the effect of checkpoint inhibitors. The possible partners fall in three buckets: compounds that further ease up on the immune system’s brakes, molecules that hit the immune system’s gas pedal, and drugs that fine-tune the environment near a tumor to make it friendlier for T-cell attack.

Out of the morass of next-generation immuno-oncology targets, few so far have been as hot as IDO1 (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase), an enzyme involved in immune surveillance. As with PD-1, inhibiting IDO1 is a way of releasing the brakes on immune cells. The enzyme initiates a cascade of events that leads to the breakdown of tryptophan, whose by-products keep T cells from reacting to cancer cells.

Studies had shown that blocking IDO1 alone was not enough to stop cancer. But as it became clear that checkpoint inhibitors would be foundational treatments, researchers reasoned that lifting another immune brake could expand the number of patients the new drugs serve.

Between 2014 and 2015, big pharma companies spent upward of $1 billion for the rights to various IDO1 inhibitors; in subsequent years, the number of biotech companies working on the target proliferated. By the beginning of this year, about a dozen Phase III clinical studies that added IDO1 inhibitors to either Keytruda or Opdivo were under way.

Nine of those late-stage studies centered on epacadostat, a compound from Incyte that was widely considered the front-runner among the IDO1 drug candidates. The trials sprang largely from a signal of efficacy in a Phase I/II study that tested epacadostat and Keytruda in less than 60 people with a range of cancers.

But doubts over the mechanism were percolating at some firms. First, Genentech gave back the rights to an IDO1 inhibitor it had licensed from NewLink Genetics. Next, Pfizer withdrew from a partnership with the Belgian biotech firm iTeos.

Then in April, Merck and Incyte said a Phase III trial involving people with melanoma failed to show any benefit from a combination of epacadostat and Keytruda. Because oncologists see melanoma as the most likely cancer to respond to immunotherapy, confidence in the field plummeted. Big pharma companies swiftly dropped or pared back late-stage studies.

Although epacadostat was hardly the first cancer immunotherapy to fail, the combination study was the first to so publicly implode. And although the field has seen some gratifying successes—in April, for example, data from a Phase III study adding Keytruda to standard chemotherapy were heralded by oncologists as a paradigm shift in lung cancer treatment—wins have yet to materialize in large trials that pair checkpoint inhibitors with experimental immunotherapies.

The IDO1 story is a cautionary one for a field that is trying to quickly navigate a tangled web of combinations—without enough care, some critics say. Other immunotherapies in earlier stages of development have seen similar levels of hype and investment, including STING agonists, certain cytokine targets, and oncolytic viruses. The concern is that companies could again jump into multiple large, ill-fated trials.

That worry was reinforced when the industry got an early look at data on other trials combining checkpoint inhibitors and novel immunotherapies. The full data will be presented this week at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting. So far, with a few exceptions, the benefit of adding experimental immunotherapies has been modest.

“There’s a lot of talk about these” immunotherapy combinations, says Roy Baynes, head of global clinical development at Merck, “but I’m not aware of any trial that has convincingly shown that the combination is better than PD-1 alone.”

Immuno-oncology by the numbers

6

Checkpoint inhibitors approved across cancers that include: melanoma, lung, kidney, bladder, gastric, head and neck, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Merkel cell carcinoma.

~$150,000:

Annual cost of treatment with Keytruda or Opdivo

~250:

Small molecule- and antibody-based immunotherapeutics in clinical studies

+1,100:

Clinical trials in 2017 that combined a checkpoint inhibitor with another treatment

1.7 million

People in the U.S. expected to be diagnosed with cancer in 2018

609,000

People in the U.S. who will likely die from cancer in 2018

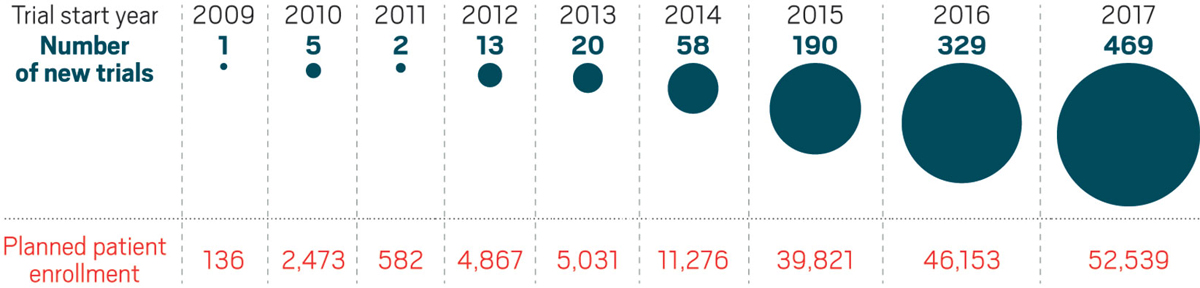

The most common partners for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs in trials in 2017

Model mayhem

Hindsight being 20/20, many say the rush into IDO1 inhibition and the subsequent letdown was avoidable. Seeing more than 250 other immunotherapies coming down the pipeline, oncology researchers are debating what to take away from the experience. They hope to tip the scales so the successes outweigh the disappointments.

But the field faces three big challenges: how to gauge a treatment’s value before it goes into human tests, how to develop measurements that can confirm a mechanism is working and allow the right patients to be given a drug, and how to design clinical trials that are efficient and deliver meaningful results.

One of the most difficult aspects of cancer immunotherapy is the very nature of the treatments. Drugs that modulate the immune system differ from earlier cancer therapies—traditional chemotherapies and newer targeted therapies that block the activity of an errant protein—because researchers often have little indication of how they will work until they are tested in humans.

Advertisement

The problem is that laboratory models for immunotherapies “have at this point almost unknown predictive value,” says Jeffrey Engelman, global head of oncology at Novartis. “We pretty much go into the clinic based on conceptual ideas and hypotheses.” As a consequence, he adds, “we’ve seen a lot of failures, and I think we’re going to see a lot more.”

As David Berman, who runs immuno-oncology at AstraZeneca, puts it bluntly: “Everything works in mice.” And while animal models have improved in recent years, “they aren’t as helpful as they were in other types of therapy—and even there, it’s questionable how much predictiveness they have,” adds Joanne Lager, who leads oncology development at Sanofi.

Indeed, preclinical tools have not kept up with the explosion in drug candidates. The first real tests of biological hypotheses are often happening in humans.

“Obviously the immune system is very complex; people have appreciated that for some time,” says David Feltquate, head of oncology development at Bristol-Myers Squibb. “But this is an example of where the technology has not caught up with where it needs to be to understand it from a clinical perspective. Sometimes you can’t do anything short of running the experiment.”

Clinical conundrums

As hypotheses are tested in the clinic, researchers are keen to learn what is—and isn’t—working in designing human studies that can efficiently yield clear information about combined mechanisms.

A major challenge has been identifying who will respond to immunotherapy, which is necessary for enrolling the right people in clinical studies. When the field started to take off, targeted therapies dominated drug portfolios. Researchers could rely on genetics to winnow out the right patients for those treatments.

People were looking for those same kind of ready-made biomarkers in immuno-oncology, says AstraZeneca’s Berman, who previously worked at BMS, where he helped develop the first approved checkpoint inhibitor, an anti-CTLA-4 antibody called Yervoy. In fact, Berman laughs, “I looked for that with CTLA-4 for a long time, and I never found it.”

The problem is that immunotherapies target the immune system, not the tumor, yet researchers also need to recognize the complex environment around the tumor. “People would love to solve it and make it simplistic, but we’re just not there yet,” Berman says.

With PD-1 inhibitors, companies—Merck in particular—have had some success at determining whether a tumor expresses PD-L1, the natural ligand for PD-1. But that biomarker hasn’t been the predictor everyone hoped for. Some patients with PD-L1-deficient tumors still benefit from anti-PD-1 drugs; others who have tumors rich in PD-L1 fail to respond.

As more therapies are tested in combination with checkpoint inhibitors, more care should be used to collect meaningful measurements, researchers say. “In a lot of cases, there are some reasonable candidate biomarkers, starting with expression levels of a molecule that’s being targeted, that are not being evaluated in as robust a fashion as they could or should be,” Johns Hopkins’s Pardoll says.

Oncology experts point to IDO1 inhibitors as an example of an area where biomarkers could have been deployed more effectively. Companies were confident their drugs were working as advertised because they could measure a metabolite of their target in the blood. But, Pardoll points out, none of the early trials looked at whether tumors were expressing IDO1 in the first place or, if the enzyme was there, whether levels were high enough to matter.

Others say studies should not just prove that a drug is hitting its target—a measurement companies are comfortable with—but rather demonstrate that it is igniting the immune system.

When the early anti-CTLA-4 studies were run, researchers’ ability to understand a drug’s effect was rudimentary: They could look for only broad T-cell activation in blood samples. But the majority of a cancer patient’s immune cells are tackling things that have nothing to do with the tumor.

Since that time, researchers have developed better tools to track the travel of specific kinds of immune cells. “You’re able to identify the needle in the haystack that is relevant to the tumor,” AstraZeneca’s Berman says. “That’s the type of technology that will help us monitor whether therapies we’re developing are clinically relevant or not.”

Indeed, BMS’s Feltquate points out that no one looked at whether IDO1 inhibitors were prompting T cells to invade tumors. “If people had waited, or more effort was put into seeing that before moving forward, the field might have slowed down a bit,” he says.

Seeking singletons

The epacadostat-Keytruda trial failure reinvigorated an already-spirited conversation among oncologists and drug developers about the qualities needed in the next wave of immuno-oncology drugs.

Among the most debated questions is whether experimental compounds need to work alone—display “single agent” activity—before being paired with drugs like Keytruda or Opdivo. Epacadostat can’t stop tumors from growing; drug companies dove into combination trials on the belief that it would work synergistically with checkpoint inhibitors.

Opinions on the need for single-agent activity vary wildly. Some experts see the lack of it as a warning sign that should be heeded. “The IDO data is very sobering” for other companies combining an inactive molecule with a checkpoint inhibitor and hoping “there’s going to be a magical effect,” Novartis’s Engelman says.

Berman says he’s seen no evidence that an inactive drug can boost the effect of an immunotherapy. “I think you need to combine molecules that are active in order to expect something additive or synergistic,” he says.

If industry scientists are circumspect about molecules that aren’t active on their own, academic researchers are less concerned. Many point out that some approved drugs need to be paired with chemotherapy or other agents in order to be effective. The best-known example is Herceptin, the HER2-targeting antibody that changed the paradigm for breast cancer treatment.

Moreover, in early-phase trials, no one knows what kind of activity is needed to accurately predict efficacy in combination studies. As MD Anderson Cancer Center oncologist Timothy Yap notes, “single-agent activity” could mean a range of things—the ability to stabilize tumors versus shrink tumors, for example. And no one has defined how long that activity needs to last.

Incyte executives say their strategy with epacadostat was the appropriate one. CEO Hervé Hoppenot points out that the options were to run a 200-patient, randomized Phase II trial before initiating a 600-patient Phase III or to save several years by going straight to a Phase III. Because the safety of epacadostat was well established, Merck and Incyte chose the latter route.

“If IDO was to be redone ... we would probably come to the same conclusion today,” Hoppenot says.

Smarter studies

Even as companies grapple with how to make smart, fast decisions about immunotherapies, they acknowledge that drug development isn’t going to get easier. Each clinical advance raises the bar for the hundreds of other therapies in the pipeline. For example, the recent data showing the impressive effect of combining Keytruda and chemotherapy to treat lung cancer—adding immunotherapy halved the risk of dying—will make it tough for other drugs to carve out territory.

The question remains whether any other immunotherapies can demonstrate a similar leap in efficacy when added to checkpoint inhibitors. More likely, oncology experts say, is that the benefit of adding most agents will be modest. Clinicians will need to carefully design their studies to capture that effect.

“There’s a reason it used to take 10 years to do these clinical trials,” University of Chicago’s Luke says. If new drugs aren’t going to build dramatically on the effects seen with anti-PD-1 drugs, many more people need to be treated to see an effect.

If any lesson emerges from the IDO1 story, experts hope it will be about the value of running well-planned, randomized studies—a staple of drug development that got lost in the gold rush—before launching large, Phase III trials. “I think that what should be done, and I hope will start to be done, is more robust Phase II trials,” Luke says.

“The lesson learned is that we need to do much better trials, specifically randomized midstage trials,” agrees Brad Loncar, a biotech investor who focuses on cancer immunotherapy. “But we’ll have to see if that comes to fruition. The market forces might be too strong.”

Company executives concede the pressure has never been higher to figure out if a drug can build on the already-strong foundation offered by checkpoint inhibitors. “There’s always this tension, especially in this really competitive environment, to make your best bet and run rather than to spend a lot of time trying to figure out how to do it,” Sanofi’s Lager says.

With so much to be sorted out, Loncar offers a gentle reminder that immuno-oncology development is still in its infancy. Keytruda, after all, was first approved in 2014. “Think about that,” he says. “It feels like it’s been a decade, but it’s four years, which in drug development terms is like two minutes.”

Between the wins and the losses, the pace is breathtaking. “If you fast-forward five or 10 years from now,” Loncar adds, “it’ll be pretty shocking and exciting how far some of these have gone.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter