Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

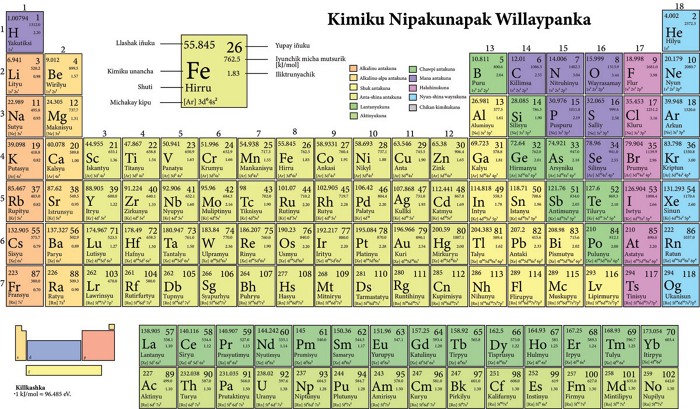

Periodic Table

Adapting the periodic table into Kichwa

A team including native speakers created a periodic table in an Indigenous South American language

by Sam Lemonick

November 16, 2021

The periodic table is part of the bedrock of chemistry education. Students use it to look up values like an element’s atomic mass, and it serves as a visual reference for the trends in physical properties. But what use is it if a student can’t read it?

Researchers tried to solve that problem for native speakers of Kichwa, a language spoken by about half a million people in parts of Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru (J. Chem. Educ. 2021, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00383). The Kimiku Nipakunapak Willaypanka (periodic table of chemical elements) presents Kichwa words for all 118 elements and other terms, like atomic weight. The researchers say the adapted periodic table will help Kichwa speakers learn chemistry.

“We think science can be part of Kichwa, and Kichwa can be part of science,” says Santiago D. Gualapuro-Gualapuro, a native Kichwa speaker and member of the team. Gualapuro-Gualapuro, a linguistics PhD student at the Ohio State University, is part of the Kichwa Institute of Science, Technology and Humanities, which works to support Kichwa communities through a scientific, cultural, and technological lens. Project leader José E. Andino-Enríquez, who graduated as a chemistry major at Yachay Tech in 2020, approached the group for help. Gualapuro-Gualapuro says the periodic table is totally new to Kichwa. He and Andino-Enríquez agree that the lack of scientific texts in Kichwa can prevent speakers from advancing in mainstream education. At the same time, having Kichwa words for elements could help Kichwa speakers communicate local knowledge of, say, medicinal plants to non-Kichwa speakers, Andino-Enríquez says.

The other research team members include Sisa P. Chalán-Gualán, a native Kichwa speaker and a chemistry student at Yachay Tech; three others from the university’s School of Chemical Sciences and Engineering; and Simone Belli, a social psychologist at Complutense University of Madrid.

The researchers started their adaptation by translating element names into Kichwa in different ways. For some elements, like helium, the team used the element’s etymology to make a new Kichwa word. Helium comes from the Greek word for the sun, so they proposed “intiku,” from the Kichwa words inti (the sun) and ku (belongs to). For other elements, they transliterated the sound of the English word into Kichwa, so nickel became “nikil.”

The group then used an online survey to ask almost 150 native Kichwa speakers whether they approved of the group’s element names and periodic table terms. In some cases the survey asked respondents to rank different possible adaptations of element names. The researchers note that many of the respondents preferred names that sounded similar to the words for the elements in Spanish, the language most widely spoken in Ecuador, even in cases where a particular sound doesn’t exist in Kichwa. That was true for several elements with an f sound, like fluorine.

Translations into indigenous languages are important for a number of reasons, says Sibusiso Biyela, a science communicator who has worked with other people to translate science texts into Indigenous African languages. “For people to feel included in the process of science, it helps to be able to understand science in their own language, because a language carries with it the values and traditions of a certain culture,” he says. He adds that the group’s surveying of Kichwa speakers as part of the translation process also gives non-Kichwa speakers insight into what Kichwa communities know and value. By involving native speakers in the adaptation process the group may have been able to create a periodic table that Kichwa communities are more likely to use.

Erwin García Hernández of the Higher Technological Institute of Zacapoaxtla is a chemist who contributed to translating the periodic table into Nahuatl, spoken by people native to regions of Mexico and Central America. Hernández emphasizes the importance of the researchers’ decision to solicit input from speakers of different Kichwa dialects. “This will allow a good understanding between the people of different zones,” he says in an email.

Georgina Stewart, an education professor at Auckland University of Technology and an expert on the Maori language and science education in that language, commends the researchers for tackling a difficult topic.

But in a written response to questions from C&EN, she explains that the same things that often motivate translations of scientific texts into Indigenous languages—helping native speakers of a language learn about and engage with mainstream science, and giving a language continued relevance in the globalized world—can also limit the translations’ usefulness. She points to the group’s Kichwa adaptation of hydrogen as one example. Survey participants preferred a name the researchers coined in Kichwa, yakutiksi, which means “water bearer,” similar to the etymological roots of hydrogen. But Stewart says that because English is the international language of science, Kichwa-speaking students who want to study at a university would be better served by a periodic table with adaptations that either sound like the English hydrogen or act as mnemonic devices, like a word that means “first gas.”

Gualapuro-Gualapuro acknowledges that Kichwa speakers will need to learn English to be successful in international science. But he doesn’t think that reality diminishes the value of a Kichwa periodic table as his group has approached it. “Each language has its own way of encoding messages,” he says, and the Kichwa language embodies the Kichwa civilization. “We want to claim our space in the world.”

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has prevented Andino-Enríquez’s group from introducing the Kichwa periodic table into a classroom, but the group hopes that will change soon. They plan to travel this month to Kichwa villages to show off their periodic table and demonstrate some chemical reactions. And the group is hoping to develop other written materials, including a manual in Kichwa describing laboratory practices and a book about the elements in Kichwa and Spanish. Andino-Enríquez says they hope to meet with officials at the Ecuadoran Ministry of Education to find ways to integrate these resources into bilingual schools.

CORRECTION

This story was updated on Nov. 22, 2021, to clarify that José E. Andino-Enríquez is no longer affiliated with Yachay Tech. He graduated in 2020.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter