Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Periodic Table

Element collecting: A niche hobby that connects people to chemistry

Enthusiasts assemble personal museums of metals, minerals, and other matter as they strive to collect them all

by Bethany Halford

June 29, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 26

Element collecting can start harmlessly enough. A rainbow-hued bismuth crystal catches your eye at a science museum one day, you buy a sample or two, and the next thing you know, you’re spending $1,500 on eBay to purchase pure silicon boules, left over from computer-chip manufacturing.

The niche hobby attracts chemists and nonchemists alike to gather metals, minerals, and even gases, using the periodic table as their guide.

“There’s something really appealing about having the building blocks of the universe in your possession,” says Matthew Field, an element collector who created and now moderates the element-collection subsection on the website Reddit. Field has a small but growing element collection inspired by his community college chemistry professor, who would bring in element samples to show to the class.

“I found out that I could just go on eBay and buy this stuff,” Field says, and that inspired him to start his own collection. Field isn’t a chemist, but he says element collecting is something nonchemists can do that connects them to science. Plus, he says, “it’s a superfun hobby.”

For many element enthusiasts, the quest to collect them all is what’s appealing. Many build their collection bit by bit over years. Others just like the idea of having all those building blocks within their reach and contact companies to create displays with all the samples already supplied.

For James L. Marshall, it’s been about the quest. And element collecting has been more than a hobby—it’s been his way of life. In a modest townhome less than an hour’s drive north of Dallas, Marshall keeps one of the world’s most remarkable personal element collections. Six meter-wide floor-to-ceiling cabinets house samples of every element up to uranium (with stand-ins for short-lived or dangerous compounds).

Shiny lead crystals, a globe of neon gas, and even a tiny sealed ampule of bromine, its headspace tinged red, compete for space on the illuminated shelves. It’s one of three element collections Marshall has assembled, including one at the University of North Texas, where he is a professor emeritus, and a portable collection he carries when he gives lectures at high schools and colleges.

But what is most noteworthy in Marshall’s collection are the minerals. He and his late wife, Jenny Marshall, collected mineral samples for each element from the original site where it was discovered or mined. They purchased most of them, but some they collected, along with “element stories”—memories of their journeys and tales of chemical history—during a decade of travels through Europe and North America.

The Marshalls documented their travels and the chemical history of the places they visited in an interactive DVD called Rediscovery of the Elements, a nod to Mary Elvira Weeks’s 1933 book Discovery of the Elements, the seventh edition of which Marshall says served as a sort of travel guide. They also wrote a series of articles in the Hexagon, a quarterly magazine published by the professional chemistry fraternity Alpha Chi Sigma.

After a decade of wandering the world, Marshall says, he was ready to stop the project. But Jenny insisted they create a Rediscovery of the Elements website. Jenny was more computer savvy than Marshall, and when she died in 2014, the project was put on hold. But last year Marshall completed the website, where visitors can see over 5,000 photographs of the couple’s elemental journeys and even create an itinerary of their own with GPS coordinates that Marshall provides for each elemental discovery site. (He graciously constructed a 10-day itinerary for C&EN. See box.)

Carmen Giunta, a chemistry professor at Le Moyne College, recently used the Marshalls’ database to create Places of the Periodic Table, a searchable, interactive map of sites associated with the elements. It includes sites where elements were discovered or created, where mineral sources of elements were mined, and other points of interest.

Giunta spoke about the project and presented a poster at the American Chemical Society Spring 2019 National Meeting in Orlando, Florida. “It was neat to see what caught different people’s interest,” he says. Giunta hopes people will use the map to explore and satisfy their curiosity about the elements.

As for Marshall, he says his next and final project will be to put everything on paper, in a photo book of his travels. He admits it will be a tremendous task “because the photos are multitudinous.”

The late author and neurologist Oliver Sacks visited the Marshalls in 2000 to see their collection. In a 2004 C&EN article, Sacks said, “I sensed a huge richness—an immediate warmth—in examining the collection. There’s a museum-like quality about it, but a highly personal quality as well. Equally wonderful are the stories of the places and people, the excursions into history and the geography.”

Sacks, like Marshall, was an element collector. He picked up the hobby as a child and wrote about it in his book Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood. Shortly before his death from cancer in 2015, Sacks wrote in the New York Times that he was once again surrounding himself “with metals and minerals, little emblems of eternity,” describing parts of his beloved element collection.

Kate Edgar, executive director of the Oliver Sacks Foundation, says Sacks had a sizable collection. “While much of it was on display at any point in time, eventually it grew to boxes and boxes, if one includes the minerals as well. He could recite all the elements in each mineral sample.”

Sacks’s partner, Bill Hayes, says these element samples were Sacks’s most treasured possessions. “He loved showing these to guests, visitors, and friends and trying to get them to guess what they are.” Hayes inherited the collection—approximately 350 specimens of elements, minerals, and fossils—which is now stored in his new apartment.

“Oliver could easily identify any of the specimens by sight, so I found that many were not clearly labeled,” Hayes says. “But after his death, I had a mineralogist and a botanist come by to ID and label everything they could—thank goodness—and Kate [Edgar] knew the history and identity behind a number of them.”

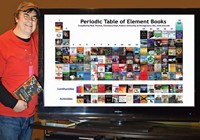

Identifying the 2,500 or so samples in Theodore Gray’s element collection will be easier. Gray, author of the popular chemistry trilogyThe Elements, Molecules, and Reactions, has documented his element collection on a website devoted to the periodic table.

Gray says most of his collection is in his office at Wolfram Research. A few samples are in drawers within his “periodic table table,” a handcrafted wood table Gray made that’s shaped like the periodic table (and that garnered an Ig Nobel Prize). “Some bigger samples are out on the floor, and the more dangerous radioactive ones are at another location,” he says.

The ultimate road trip for element collectors

Element enthusiast James Marshall spent a decade traveling the world with his wife, Jenny, to visit the sites where elements were discovered or mined. He planned a 10-day trip through Germany and the Czech Republic to visit chemically important sites highlighting 39 elements of the periodic table. Visit cenm.ag/roadtrip.

As for what will happen to Gray’s vast collection when he dies, he says perhaps a science museum will take it. “More likely, I will fail to deal with the issue in time, and it will become a burden on my children,” he jokes.

For a few years, Gray collaborated with the company RGB Research to create periodic table displays for companies, museums, schools, and private collectors. They’ve made displays for Dow, California Polytechnic State University, and Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates’s office.

Marcos Palomo, a cabinetmaker, started working with RGB Research to construct its display cases, but last month he took over the entire company, renaming it 118 Displays and stepping in as its CEO. “We specialize in the creation of samples that are meant to be decorative and to illustrate what the elements actually look like and spark interest in people,” Palomo says. “We often create samples that surprise chemists who have been working with these elements all of their lives.”

Palomo says working with elements can be tricky. “Many of them tarnish and degrade in the presence of oxygen, so that means a lot of the work we do has to be in a glove box under argon” before sealing them into displays. Costs range from $10,000 to $100,000, Palomo estimates.

For those who would like a ready-made element collection but don’t have the budget or space for a large display, brothers Cory and Tim Marriott of Engineered Labs have an offering. They have created a handheld, acrylic periodic table that contains 83 element samples. It even includes tiny bubbles of some of the gases (chloride and bromide salts take the place of those reactive halogens; mercury sulfide stands in for the liquid metal).

The Marriotts introduced the display on Kickstarter last year with the goal of raising $3,000. They ultimately raised $149,302 from 611 backers. They now sell it on their website for $179.40.

At roughly the size of a romance novel, the display makes it possible to hold many of the universe’s building blocks in your hand—something that’s inherently romantic for an element collector.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter