Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

New step for better chemical decontamination

Victims wipe themselves with dry, absorbent materials

by Cheryl Hogue

April 12, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 15

An industrial chemical accident. An attack with a chemical warfare agent. Either of these situations can leave many people in acute need of decontamination.

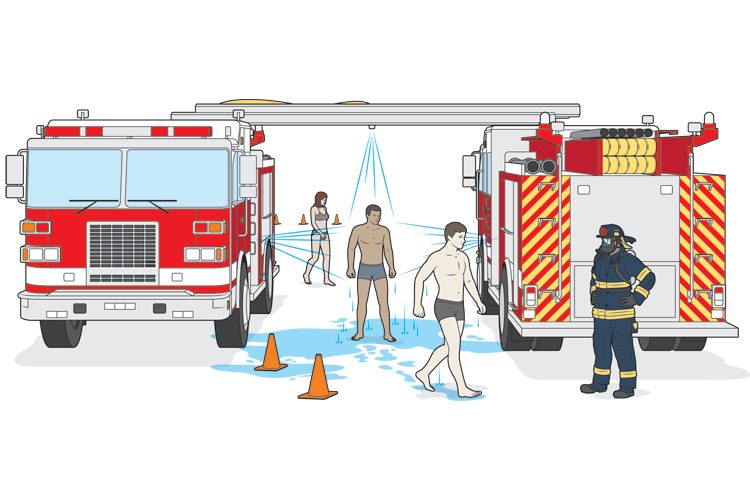

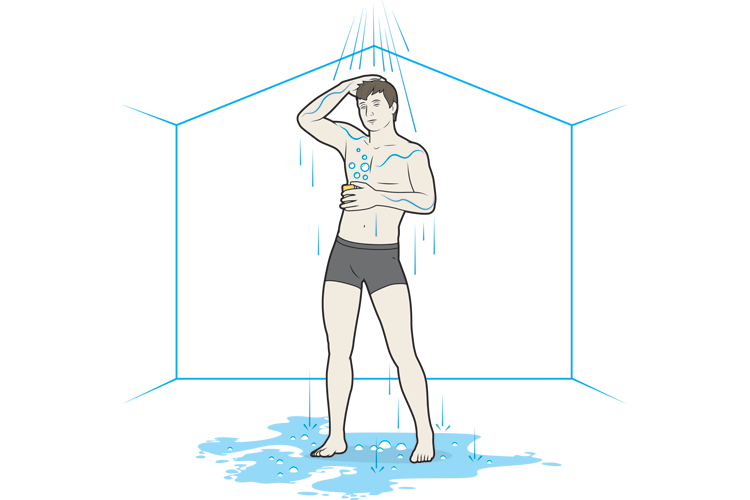

Until recently, the US government’s decontamination protocol for first responders dealing with people exposed to most types of liquid chemicals had two major steps. First, affected people would strip off their clothes and walk through a spray of cold water provided by two fire trucks hooked up to a fire hydrant. Next, victims would take a warm, soapy shower set up in a tent.

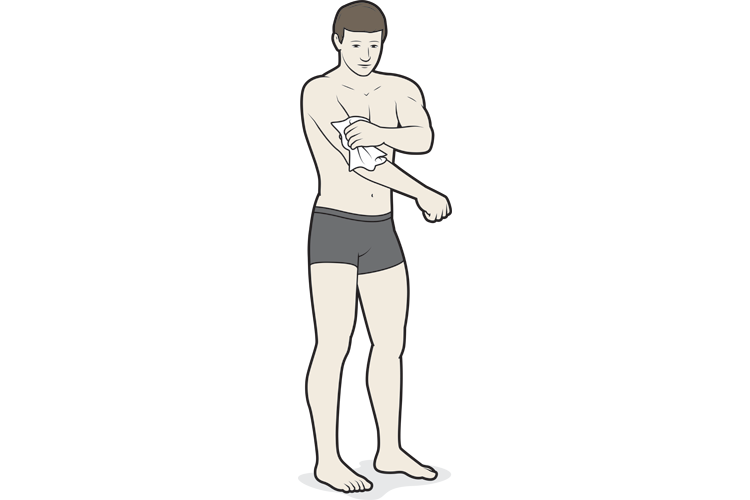

Now, citing evidence in a peer-reviewed study, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has added a new step to its decontamination guidance for chemical incidents (Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.06.042). It calls for exposed people to first wipe themselves off with dry, absorbent materials, such as paper towels or diapers, before they pass through the water spray.

Step One

Step Two

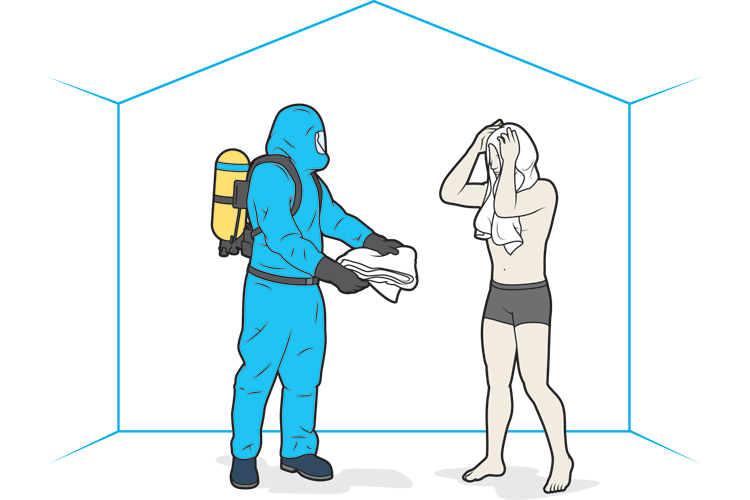

Step Three

Step Four

Step Five

The main reason for this new step, dubbed dry decontamination, is time.

“If you’ve got something which can kill you very quickly, the sooner you can get it off the skin and hair, the better,” says Robert P. Chilcott, a University of Hertfordshire toxicologist and lead author of the study. Responders may need 10–20 min to set up the water spray, called a pipe-and-ladder system. The warm shower system takes even longer to install and get operational.

The dry process is also impressively effective. A team led by Chilcott found that dry wiping, when performed under the instruction of a first responder, can remove 70–99% of a liquid contaminant from a person’s body. The research, conducted under contract with HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), involved a 2017 exercise conducted at the University of Rhode Island. Researchers applied a chemical warfare agent simulant to 80 volunteers who role-played as casualties. Local firefighters acted as first responders and led the volunteers through various combinations of decontamination procedures, including dry wiping.

Dry decontamination provides several other benefits besides speed and effectiveness. For one, it helps prevent hypothermia. “The water that comes out of a fire hydrant is less than 10 °C,” Chilcott says. “It’s cold.”

Having wet, cold people wait for a shower isn’t ideal, especially when outdoor temperatures are low, Chilcott explains. Wiping gives people a way to help themselves while both the spray and shower systems are readied so they can move quickly from cold to warm.

In addition, dry decontamination minimizes potential exposure of first responders and medical personnel, Chilcott points out. And it cuts back on the accumulation of hazardous material in the subsequent decontamination steps, says Rick Bright, director of BARDA.

HHS is spreading the word about the new dry-wiping step. The department recently integrated the dry decontamination step into guidance for first responders called Primary Response Incident Scene Management.

Plus, HHS and the University of Hertfordshire crafted a tool to help first responders determine which approaches to decontamination will work best in a particular situation. Called the Algorithm Suggesting Proportionate Incident Response Engagement, or ASPIRE, this tool is integrated with the new decontamination guidance in a mobile app called the Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders, or WISER.

Chilcott warns, however, that “dry decontamination isn’t a universal panacea. It only works for liquid contaminants.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter