Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Safety

Newscripts

Your ducky’s microbiome, glow-in-the-dark squirt guns

Toys inspire biology, biology inspires toys

by Melody M. Bomgardner

May 14, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 20

Tub-time trouble

Kids are too young to conjure up Janet Leigh’s iconic shower scene, but Newscripts has been practicing Leigh’s Hitchcockian scream in response to recent news about another threat to bathers—rubber duckies.

Sure, sure, they don’t look like psycho killers, with their wide eyes and orange beaks turned vaguely upward. And even if you winged one at your brother’s head, it wouldn’t really hurt since they’re made of soft plastic.

But the truth is the duck is not so innocent. Indeed, it already has an entry on its rap sheet. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission has fingered rubber ducks as an example of products that could contain harmful levels of certain phthalates, which are additives used to make plastics more squeezable.

And all along, the duckies have been brewing an entirely different sort of trouble, according to researchers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science & Technology. Turns out, the squishy beasts attract an unsavory crowd of microbes.

The ducks host a veritable microbial buffet, particularly on their insides. Their flexible polymers attract organic molecules from the water and are themselves a source of carbon released from plasticizers, stabilizers, and antioxidants. That stuff becomes food for microbes that lurk in bath water, which might start out cleanish but doesn’t stay that way after a dirty kid splashes around in it.

Frederik Hammes and coauthors wanted to know precisely which organisms are hanging out in the toys and where they came from. Hammes and colleagues used optical coherence tomography and high-resolution scanning electron microscopy to measure and image the thick layer of organisms, or biofilm, inside bath toys previously owned by actual children.

The 19 toys studied contained roughly 1.3 × 109 bacterial cells each. Like the inside of a human, the inside of a rubber ducky has a unique microbiome (npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2018, DOI: 10.1038/s41522-018-0050-9). The real toys and even some control toys, which had been placed in clean or dirtied bath water, hosted potentially harmful microbes, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa,species of Listeria, and Legionella pneumophila.

While Hammes acknowledges the ick factor of the discovery, he stresses that his team isn’t interested specifically in the bad germs but rather the overall microbial ecology of the ducks. They were able to identify many different populations, including fungal species, by using next-generation DNA sequencing.

If this research inspires you to cut open your own household’s bathtub toys, proceed with caution. Hammes tells Newscripts that obtaining research objects for the study required “heavy negotiations with unwilling toy owners, via their parent of course, on what would be suitable replacements.” Anyway, he suggests replacing the old toys with ones without a hole on the bottom to let in dirty bath water.

Glow guns

If you are going to sacrifice your kid’s tub toy for science, maybe do it after an evening bath when you can distract him or her with a toy that actually benefits from its brush with biology. Get two or more BioToy squirt guns, and add some clean water—not from the tub—and a set of special tablets. Soon you’ll have a glow-in-the-dark water fight.

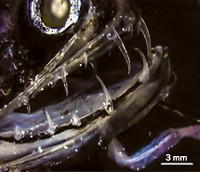

The tablets contain luciferin, a molecule that emits light when activated, and a light-activating protein called luciferase. The luciferase is a human-made version of a molecule from a small, bright deep-sea creature called Gaussia princeps. The flashy copepod lives at an ocean depth of over 600 meters, so putting a bunch directly in a water pistol would not be very practical.

Advertisement

Instead, Bruce Bryan and other founders of BioToy figured out the gene inside Gaussia that makes the glow-making protein. The same science underpins NanoLights technology, a bioluminescence technology used in biological research. It helps scientists view the functions of genes and molecules inside living cells and study drug activity.

As BioToy puts it plainly on its website, “Creating a squirt gun that could emit bioluminescent water required years of research in biochemistry and engineering.”

Never mind the years of research. What the kids hanging around Newscripts want to know is when they can get their hands on the squirt guns and how late they are allowed to stay up shooting them. According to BioToy, the glow lasts for three to four hours.

Melody Bomgardner wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter