Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Art & Artifacts

Ancient Egyptian embalming fluids suggest long-distance trade

Scientists were surprised at the complexity of the chemicals used to preserve bodies for the afterlife

by Payal Dhar, special to C&EN

August 31, 2023

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 101, Issue 29

The funerary practices of the ancient Egyptians can still reveal surprising information. In a recent analysis of the 3,500-year-old remains of the noblewoman Senetnay, found in jars in the Valley of the Kings, researchers found a mixture of ingredients that appear more complex than the era’s common embalming fluids.

Along with the typical plant oils, animal fats, beeswax, and bitumen, the study found evidence of fragrant resins from trees that grow in the Mediterranean and in Asia.

The complexity of the embalming fluid not only hints at Senetnay’s high status but also suggests that the Egyptians might have had connections with distant lands much earlier than previously thought (Sci. Rep. 2023, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39393-y).

One of the compounds was a coniferous resin, most likely from the larch, a tree that grows in the north Mediterranean. Another surprise was what appeared to be dammar, a resin that comes from South and Southeast Asia. The resin has been found in other mummification balms but only those from later periods, notes Barbara Huber, an archaeological chemist at the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology who led the study. If the presence of dammar was confirmed, she says, “we would have evidence of long-distance trade a millennium earlier.”

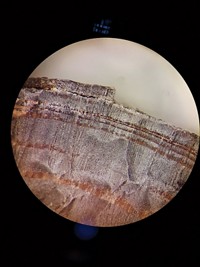

Huber’s team scraped samples from inside the funerary jars. Inspired by previous studies on the composition of embalming fluids, the group used mass spectrometry (MS) to check for specific compounds. Techniques like gas chromatography/MS (GC/MS), liquid chromatography tandem MS and high-temperature GC/MS allowed the researchers to identify the individual components with high precision and sensitivity.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter