Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Winning by a Nose

Laureates' research has demystified the sense of smell

by Amanda Yarnell

October 11, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 41

Two U.S. researchers have won this year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for shedding light on the inner workings of the sense of smell.

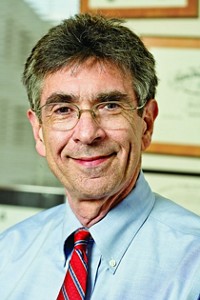

Scientists had long wondered how the olfactory system recognizes and remembers more than 10,000 different odors. Richard Axel, 58, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Columbia University, and Linda B. Buck, 57, an HHMI investigator at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, share this year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine--and its nearly $1.4 million cash award--for solving this mystery.

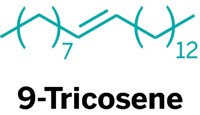

Most scents arise from a cocktail of molecules known as odorants--peppermint, for instance, gets its characteristic odor from a mixture that includes menthol, menthyl acetate, and menthyl valerate. Olfactory researchers had been hunting for the proteins expected to bind and sense odorants in the nose but had come up empty-handed.

That scenario changed in 1991 when Axel and Buck, then a postdoc in Axel's lab, published a paper describing a large family of genes that code for membrane-spanning receptor proteins found in a small patch of cells inside the nose. Mice make an astonishing 1,000 or so different kinds of these odorant receptor proteins. Humans, who don't rely as much as mice on their sense of smell, make about 350 different ones. Axel and Buck showed that these odorant receptor proteins belong to a family of proteins called G-protein-coupled receptors, a class that also includes the rhodopsin proteins that initiate vision.

"Olfactory research can be divided into two eras: before and after this paper," comments olfactory researcher Peter Mombaerts of Rockefeller University. "While the term 'breakthrough,' is all too often used, I believe this paper is one of the clearest examples," he adds.

Later, Axel and Buck--who started her own lab after her postdoc stint with Axel--independently showed that each cell in this region expresses only one type of odorant receptor protein. Each odorant molecule in a given scent activates several different types of odorant receptor proteins. As a result, a given scent gives rise to a unique signature of activated cells, allowing the brain to recognize and remember more than 10,000 smells with only hundreds or so different kinds of odorant receptor proteins.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter