Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Bisphenol A Vexations

Two government-convened panels reach nearly opposite conclusions on compound's health risks

by Bette Hileman

September 3, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 36

WHEN IT COMES TO safety issues, the high-production-volume chemical bisphenol A (BPA), which is used to make polycarbonate food and drink containers and is found in plastic resins, has engendered sharp controversy. This controversy was highlighted over the past month as two government-convened groups came up with almost diametrically opposed assessments of potential human health risks from BPA.

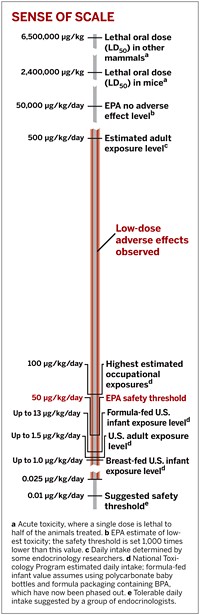

The findings of one of the groups—a collection of 38 scientists that gathered in Chapel Hill, N.C., in November 2006 for a workshop on BPA organized by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS)—were published last month in Reproductive Toxicology. Most significant, this panel of researchers published a consensus statement concluding that in rodents, low doses of BPA cause breast cancer, enlarged prostates, hypospadias (abnormalities of the penis), reduced sperm counts, early onset of puberty in females, type 2 diabetes, and adverse neurological effects analogous to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The group noted that human exposure to BPA is within the range that induces these adverse effects in lab animals.

As such, the Chapel Hill group warned, the wide range of problems seen in animals is "a great cause for concern with regard for the potential for similar adverse effects in humans." Part of its concern stems from the fact that the physiological effects observed in lab animals are increasing in human populations. For example, the incidence of neurological problems, such as ADHD, and of type 2 diabetes has risen sharply in children in recent decades.

In contrast, the second panel, appointed by the Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction (CERHR), a part of the National Toxicology Program (NTP), concluded on Aug. 8 that it only has "some concern" that prenatal and early childhood exposure to BPA may interfere with brain development and cause neural and behavioral effects. This panel expressed "minimal concern" that in utero exposure to BPA causes enlarged prostates or accelerates puberty, and it has "negligible concern" that humans exposed prenatally to BPA would develop reproductive tract abnormalities or any other birth defects. The panel categorized its findings into five levels of concern: negligible, minimal, some, moderate, and severe. NTP is an interagency group located within NIEHS and primarily supported by NIEHS, the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health, and the Food & Drug Administration.

The object of concern, BPA, is the monomer raw material used to make polycarbonate plastic where it is loosely bound, allowing small amounts to leach out of the finished plastic. Helping to attract public attention is the fact that the most commonly used products containing BPA include polycarbonate baby bottles and sippy cups, polycarbonate food containers, and food cans lined with BPA-based resins. Everytime people drink beverages or eat food from such cans, they are exposed to BPA. When baby bottles are heated, they leach significant amounts of BPA. Ninety five percent of Americans tested have parts-per-billion levels of BPA in their blood.

Environmental activists are pleased with the conclusions of the Chapel Hill consensus group, while industry organizations, such as the American Plastics Council, laud the results of the CERHR panel. In fact, the industry stakeholders say the CERHR conclusions show that bisphenol A poses little potential risk to human health.

Why are the conclusions of these two panels so different? One reason is that the CERHR panel was charged with considering only risks to human reproduction. For example, it was not charged with evaluating cancer risks that might develop later in life as a result of exposure to BPA.

ANOTHER REASON for conflicting results is that the CERHR panel looked at a narrower set of studies. "The body of literature reviewed was different," says Retha R. Newbold, director of the laboratory of molecular toxicology at NIEHS. The Chapel Hill group reviewed the entire body of published BPA literature, more than 700 studies. As such, it considered lab animal studies with different dosing methods—oral, injection, and subcutaneous, she says. In contrast, the CERHR panel excluded all studies in which BPA had been injected or absorbed through the skin. It decided that the oral route is the only valid route of exposure for study in lab animals.

Newbold considers that view to be a mistaken one. Oral exposure is not the only route in humans, she says. Some BPA is absorbed through the skin, some is inhaled as dust. "We do not even know how much is absorbed by different means," she explains. "The important thing is we find free unmetabolized BPA in blood, and this BPA exposes the fetus, who does not eat. We find BPA levels in human blood that are equal to the levels that cause problems in laboratory animals," she says. "For me," she explains, "the route of exposure is not as important as the dose getting to the target tissue. Also, fetuses and newborns do not metabolize BPA in the same way an adult does."

However, Robert E. Chapin, chair of the CERHR panel and head of the Investigative Developmental Toxicology Laboratory at Pfizer, insists that to produce valid conclusions, studies in which BPA was injected directly into the animals' bloodstream or administered under or through the skin had to be rejected. In studies that did not use the oral exposure route, there was great uncertainty about the relative doses, he says.

The choice to reject nearly all studies that did not use oral exposure routes eliminated most research showing adverse effects at very low doses. Even studies of this kind published in major peer-reviewed science journals were not considered. Instead, the CERHR panel relied heavily on an unpublished study by Rochelle W. Tyl, a senior fellow in developmental and reproductive toxicology at the North Carolina-based Research Triangle Institute. In Tyl's study, which was funded by the Society of the Plastics Industry, mice were dosed orally with five different levels of BPA and showed no adverse effects except at the highest levels, which were toxic and much higher than anything humans would experience.

A large number of mice were used for Tyl's study—six BPA dose groups with 28 animals in each group, as well as positive and negative control groups. One problem with such a large study, says John Peterson Myers, chief scientist with the nonprofit group Environmental Health Sciences, is that more than one technician is required to do the dissections. These are highly skilled activities subject to inter-observer variability, he says. Seemingly minor differences in the way the dissections are performed could obfuscate any differences in prostate weight caused by BPA exposure, Myers says.

A further problem with the CERHR report, says Maricel V. Maffini, a research assistant professor at Tufts University School of Medicine, is that the criteria established by the panel to include studies for consideration "were not applied uniformly throughout the document." One example is that the CERHR panel "arbitrarily considered seven as the adequate number of animals to be included in an experiment in order for it to be considered valuable," she says. But there are no explanations of why seven animals are minimally adequate, she adds. Moreover, Maffini notes that a number of studies cited in the panel's report use fewer than seven animals.

Another possible explanation for the conflicting conclusions is that there were different qualifications for membership on the CERHR and Chapel Hill panels. The scientists on the CERHR panel were chosen explicitly because they had never done research on BPA. In contrast, the 38 scientists in the Chapel Hill group convened by NIEHS had all published extensive BPA research. For example, Frederick S. vom Saal, professor of biology at the University of Missouri, Columbia, who has done more research on BPA than any other individual scientist, was excluded by CERHR. In contrast, when the National Research Council produces a report on a topic, it routinely appoints to its committee scientists who have published extensively on the topic. But it is the general CERHR policy to recruit scientists who have not conducted research on the chemical under review.

Chapin defends the practice. "We want people who can look at a lot of different data in a disinterested way," he says. "If we hired people who have published in the field, the discussions would have deteriorated into shouting matches."

James Huff, associate director for chemical carcinogenesis at NIEHS, has a different opinion. "I was just shocked that vom Saal was not on the committee," Huff says, contending that scientists on CERHR panels should have experience with the subject compound.

In spite of the controversy, the recent pronouncements on BPA are having repercussions. Robert H. Weiss, a litigation attorney based in Washington, D.C., filed a billion-dollar class-action lawsuit on March 12 against five leading manufacturers of polycarbonate baby bottles. The suit was filed in Los Angeles Superior Court on behalf of all the babies of California who may have been injured by drinking out of the companies' polycarbonate plastic bottles, the complaint says.

THE OUTCOME of the litigation, Weiss says, hinges on violations of business and consumer codes, not on scientific assessments of the health effects of BPA. California law forbids manufacturers and retailers from selling products that are potentially harmful without disclosing the risks, he explains. Manufacturers have known for years that BPA, recognized as estrogenic since it was first synthesized, leaches from their products, he notes. "Currently, manufacturers do not have to list BPA as one ingredient on the product label," he says. "We're going to change that."

Another development is that the authors of "Baby Bargains," a best-selling guide to baby products, have advised parents to stop using bottles made of polycarbonate plastic. Until recently, the guide recommended polycarbonate bottles, which had constituted 90% of the market. "If you are shopping for bottles, choose an alternative made from BPA-free plastic or glass," wrote author Denise Fields in her August newsletter. "If you have polycarbonate bottles, throw them out."

To justify her decision, Fields specifically referred to the consensus statement of the Chapel Hill group and to the milder concerns expressed by the CERHR panel.

In her recommendation, Fields was applying the precautionary principle, a move actually suggested by Chapin near the close of the CERHR meeting when asked what advice the public should take away from the panel's conclusions. In the context of chemicals, the precautionary principle holds that even in the absence of scientific consensus, it is prudent to act as though a potentially harmful substance is in fact harmful. "It might be a time for application of the precautionary principle," Chapin said. "Adults are probably more immune to the effects of BPA, but infants and children may be more at risk."

The conclusions of the two panels are likely to prompt states to reintroduce bills banning the use of BPA in baby bottles and in other beverage and food containers meant for young children. California, Minnesota, and Maryland have considered such legislation over the past few years.

FDA has promised to evaluate the results from the two government-convened panels. "FDA absolutely still considers BPA safe for uses in food containers," says Mitchell Cheeseman, deputy director of the agency's Office of Food Additive Safety. "We are going to look at the information independently. If it causes us to change our mind, we will take appropriate action."

The last stage of the BPA hazard assessment by NTP will integrate both the CERHR report and data from the Chapel Hill consensus statement, as well as new scientific studies that were not available for either of these reports, says John R. Bucher, deputy director of NTP. The hazard assessment will be subject to public comment and peer review. If the final assessment expresses concern about health effects from BPA, it could prompt a review by California officials under Proposition 65, the law that requires warnings on consumer products if the state determines that they pose a risk of cancer or reproductive harm. The assessment could also form the basis for regulation by other states and for eventual federal regulation of the compound.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter