Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Aftermath Of Disaster

ACS Meeting News: Researchers discuss consequences of Deepwater Horizon spill

by Cheryl Hogue

September 20, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 38

Ecosystems in and around the Gulf of Mexico were hard-hit by the Deepwater Horizon explosion that spewed millions of gallons of oil into the water for 87 days from April to July. Now, the Gulf’s environment is beginning to recover, according to researchers speaking at the American Chemical Society national meeting in Boston last month.

At a jointly sponsored symposium on the Gulf gusher, scientists shared results that were mainly, but not completely, optimistic about the residual environmental consequences of the disaster. They discussed the lingering effects of the massive spill on marshy shorelines, the safety of commercially caught shrimp and fish, and how marine creatures living on the dark bottom of the Gulf are faring in the wake of the disaster.

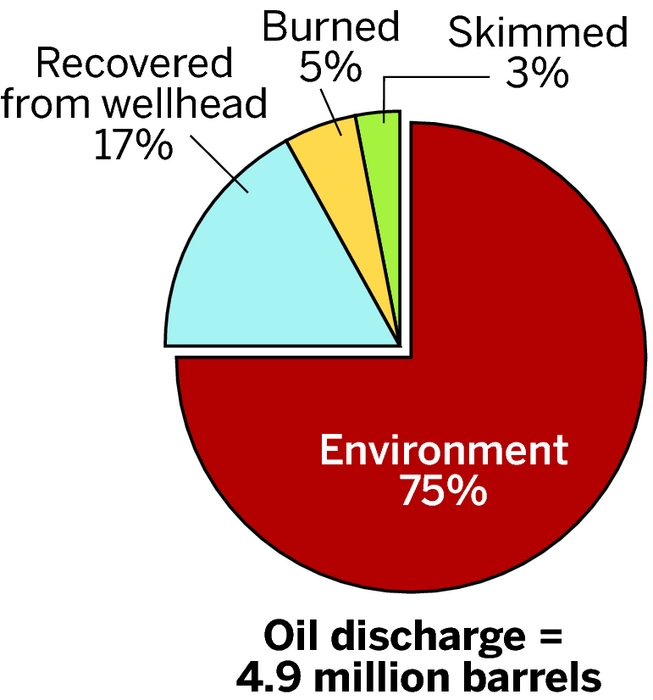

“The amount of oil is staggering,” said Edward B. Overton, professor emeritus of environmental sciences at Louisiana State University. Official estimates are that the gusher released more than 200 million gal into the Gulf.

But the spilled crude is weathering. First, the oil loses its lighter, more toxic hydrocarbons and forms sticky, floating “gunk,” Overton told attendees. Then saturated and aromatic compounds are degraded, leaving an asphaltene residue, he continued. These materials form tar balls that are primarily a nuisance rather than hazardous, he said. However, tar balls can pose a danger to sea turtles that mistake them for food and eat them, he added.

In the wake of the largest oil spill in U.S. history, Overton said, “it’s mind-boggling how fast the environment is improving.” He showed a photograph taken during the spill of a marshy area heavily coated with dark oil. Then Overton projected a more recent image of the same spot, captured in August. That photo shows green and growing grasses, with little oil visible.

Although marshlands are recovering from being covered with crude, they are suffering further damage from booms that were deployed in the water to keep oil from washing ashore, Overton said.

In a number of areas, booms have broken loose from their positions, Stephen Lehmann, a National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration official, told the audience. Now, lengths of boom drape over land along the water’s edge. Tides and storms are pushing the booms around, scouring and potentially destroying low-lying marshlands, said Lehmann, who served as a scientific support coordinator for the government’s spill response team.

Meanwhile, Erik E. Cordes, assistant professor of biology at Temple University, is looking for environmental impacts of the spill far from the marshes. Cordes studies the Gulf’s deepwater communities, where corals thrive. Unlike corals in shallow, tropical reefs, the Gulf’s deepwater corals have no symbiotic algae in their tissues to provide food. Instead, they derive their nourishment from food that drifts down from the surface.

Cordes offered attendees positive news about these corals. For years, researchers have been studying three deepwater communities that are within 60 miles of the oil-rig blowout, Cordes said. Recent photographs of these deepwater coral sites, which are at depths of 300 to 500 meters, show no discernible changes in the communities when compared with images taken in 2009, Cordes announced at the symposium.

Biologists don’t expect oil from the spill to reach the depths of these communities, which have adapted to living near natural oil seeps in the Gulf. However, researchers are concerned that toxic substances from the oil may infiltrate the food chain and eventually end up in the corals, Cordes explained. So researchers are analyzing corals, other animals, and sediments to see whether they are taking in hydrocarbons from the spill, he said.

Between the Gulf’s deepwater communities and its marshes live the shrimp and fish that many people rely on for their incomes or enjoy on their dinner plates. NOAA has reopened many commercial fishing areas that were closed during the spill.

“There are no chemicals of concern turning up in seafood” harvested from the Gulf, said John W. Finley, professor of food science at Louisiana State University. “It’s wonderful news.” Shrimp and finfish quickly metabolize aromatic hydrocarbons, such as those found in crude oil, he added.

Nonetheless, biochemist Trevor M. Penning of the University of Pennsylvania said seafood from the Gulf needs to be monitored for years, especially for the presence of polyaromatic hydrocarbons. PAHs, which are suspected carcinogens, are the most abundant hydrocarbons in crude oil and potentially the most hazardous fraction of the crude that was spewed into the Gulf, Penning told symposium attendees. In addition, PAHs are generated when meats or seafood are cooked.

Finley had less concern about PAHs in Gulf shrimp and fish than Penning did. People who eat Gulf seafood probably consume more PAHs generated by cooking it than those found in the marine creatures’ bodies due to environmental exposure, he said.

Gulf seafood may be safe to eat now, Penning countered, but PAHs from the spill could be settling into marine sediments. These pollutants could get into the food chain over the long term, especially via filter feeders such as bivalves, which include oysters, clams, and mussels. “We need to be vigilant,” Penning warned.

He called for development of better techniques to detect these compounds in human urine and blood serum. Researchers would then be able to determine whether people’s exposure to PAHs is increasing, decreasing, or staying the same, Penning said.

Meanwhile, Jeffrey W. Short, a science director for the environmental group Oceana, in his talk called for researchers studying the spill to focus their work on four basic questions about the disaster: How much oil was released by the shattered well? Where did the oil end up? What are the effects from the oil? And how long will those effects last? These are the biggest issues in the public’s mind about the spill, said Short, who recently retired after 31 years as a NOAA research chemist. At NOAA, he focused on oil pollution and worked on the aftermath of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska.

Overton pointed out that scientists have collected lots of data about the recent spill, but not much of this information has been synthesized yet.

Cosponsoring the Gulf oil spill symposium were the ACS Committee on Science, the Multidisciplinary Program Planning Group, and the ACS Green Chemistry Institute.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter