Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Monitoring A Troubling Trend

Federal agencies ready themselves to tackle ocean acidification

by David Pittman

January 10, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 2

Ocean scientists and climate observers have witnessed in the past year a flurry of government activity aimed at organizing the explosion of research on ocean acidification and facilitating national monitoring.

“The only way to halt ocean acidification is to stabilize CO2 emissions.”

The government has supported research on seawater chemistry since at least the 1980s, but over the past decade, more work has been done to specifically study the acidification of the oceans—a decrease in ocean pH due to increasing levels of dissolved carbon dioxide. This research is being accelerated thanks to the , which was signed into law in March 2009. The law brings together as many as eight federal agencies to draft a plan to tackle ocean acidification.

Among other mandates, the law creates the interagency National Ocean Acidification Program to monitor and research ocean acidification. It also spurs greater investigation by federal agencies of the phenomenon’s effect on ecosystems and strategies to conserve marine life. As a result, the National Science Foundation, a major federal supporter of such work, announced last fall nearly $24 million in special grants for ocean acidification research.

The law also requires the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration to establish a national program office for ocean acidification. And in the next month, NOAA is expected to reveal plans for its monitoring and research agenda.

NOAA is hesitant to reveal many details, but Richard A. Feely, a senior scientist at the agency’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab in Seattle, did say NOAA’s program hinges on research, monitoring, data management, education, policy, and training.

NOAA’s objectives closely mirror recommendations set forth in a National Research Council report released in April 2010. The study examined the necessary elements of a national research and monitoring program on ocean acidification. The NRC report says the key element—a broad, integrated national monitoring program, which currently doesn’t exist—should measure ocean temperature, salinity, oxygen, certain critical nutrients, dissolved inorganic carbon, pCO2, total alkalinity, and pH. Such a program would help answer vexing questions such as how coastal marine systems and human interactions impact pH levels.

The federal government’s response is in many ways the “natural progression from the recent scientific understanding that oceans are experiencing a relatively rapid change in pH and that this might have important biological consequences,” says Lisa Suatoni, a senior scientist in the Natural Resources Defense Council’s (NRDC) Oceans Program.

The chemistry behind ocean acidification—a term coined in the early 2000s—and its net effect are straightforward. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have risen almost 10% in the past 20 years. According to NOAA climate observations, atmospheric CO2 jumped from 354 ppm in 1991 to 380 ppm four years ago and to 389 ppm today. The oceans absorb about one-third of those emissions, but the recent skyrocketing amount of anthropogenic CO2 is too much for oceans to naturally buffer against.

As a result, the pH of the oceans has dropped about 0.1 units—from about 8.2 to 8.1—since the start of the Industrial Revolution, observers say. Most speculators project that the acidity will drop another 0.2 to 0.3 units by the end of the 21st century. A falling pH in the oceans sets off a domino effect of consequences for marine life that touches on reproduction and growth.

When the abundant CO2 in the atmosphere dissolves in ocean water, it forms carbonic acid, which then dissociates into hydrogen ions and bicarbonate ions. The extra hydrogen ions are likely to react with the free carbonate ions to form more bicarbonate. The net effect is less seawater carbonate—the molecule many animals use in calcification. With fewer carbonate ions in the water, it’s harder for animals that need the molecule to make shells and skeletons.

Although it’s not totally known how or if some animals will adapt to the changes, more aqueous CO2 may enhance the rate of photosynthesis for some marine plants. Scientists have found that a lower pH also affects sound propagation, altering life for a host of animals.

“One of the things that researchers are finding is that there are so many species-specific responses that until we have a wide range of studies under our belt, we’re not going to be able to make a lot of generalizations,” says Sarah Cooley, a research associate in marine chemistry and geochemistry at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, in Massachusetts.

Pulling together this research and understanding where the gaps are is one of the charges of the Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification. As mandated by FOARAM, the working group—which includes NOAA, NSF, the National Aeronautics & Space Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Navy, and the Departments of the Interior and State—has been meeting since late 2009 and will help advise the National Ocean Acidification Program. “What we had to do is define what the various roles of the different agencies were and how they could fit together,” Feely says. “As it turns out, we all had different responsibilities, so they all fit quite nicely.”

In March 2010, the working group reported to Congress an outline of ongoing research efforts across all eight agencies. The group is now working on a strategic plan for ocean acidification research that is expected to be completed in March, Feely says.

One noted occurrence at NOAA outside FOARAM’s directives is President Barack Obama’s early August 2010 nomination of Scott C. Doney, a marine geochemist at Woods Hole, to become the agency’s first chief scientist since 1996. However, his confirmation by the Senate is still pending.

“His nomination for the chief scientist spot is interesting because he is not a fisheries or physical climate scientist, which are traditionally major areas of NOAA activity,” says Edward R. Urban Jr., executive director of the nongovernmental group Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research. “Scott is probably the first biogeochemist in the position and has stronger ties to both NSF and NOAA than have previous holders of this position.”

Doney’s research focuses on the global carbon cycle, marine chemistry and ecosystem interactions, overall pH lowering in water, and ocean iron fertilization—the intentional adding of iron to spur CO2-gobbling plankton.

Research such as Doney’s is important because not much is known right now about what can reverse or prevent the effects of ocean acidification. “Ultimately, the only way to halt ocean acidification is to stabilize CO2 emissions,” NRDC’s Suatoni says. “So the solution is completely wrapped up in energy and climate policy.”

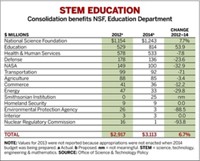

That policy, which will likely come under great scrutiny in the next two years in a Republican-controlled House of Representatives, could also be hampered by a belt-tightening Congress. FOARAM had authorized funding of $34 million for NOAA and NSF combined over the past two years. However, NOAA received just $5.5 million in that time, and NSF got nothing. “It’s inadequate,” Suatoni says of the funding levels, “and we’re going to struggle to keep it at those inadequate levels.”

Garry D. Brewer, who was on the committee that issued the NRC report, says further investigation of ocean acidification will add more ammunition for scientists to defend an aspect of climate-change science that is under heavy fire by the political right.

“If you can put science in front of it in a clear, unequivocal, and absolutely straightforward fashion, that at least increases the odds the political process will pay any attention,” says Brewer, a professor of resource and policy management at the Yale University School of Management.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter