Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Airbrushed Polymers Could Seal Surgical Incisions

Biomaterials: Researchers spray mats of biodegradable nanofibers directly onto tissues using a tool from the hardware store

by Katherine Bourzac

March 13, 2014

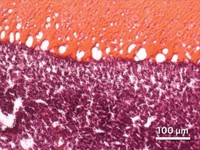

To supplement or even replace sutures, some researchers have proposed applying sticky, biodegradable mats of polymer nanofibers onto surgical incisions to seal them and promote healing. But existing methods of depositing such mats aren’t compatible with living cells and tissues. Now, for the first time, researchers have demonstrated that they can spray polymer nanofibers directly onto biological tissues using a modified airbrush from the hardware store (ACS Macro Lett. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/mz500049x).

Mats of polymer nanofibers show potential not only for use in surgery but also as biodegradable, drug-releasing implants or as scaffolds for tissue engineering, says Peter Kofinas, a bioengineer at the University of Maryland, College Park. One method of making the mats is electrospinning, which uses electric fields to spin polymer fibers onto a conductive surface. Other researchers make the polymer fibers in a centrifuge that resembles a cotton-candy machine. In both cases, the technique would damage living cells, so the fiber mats must be placed onto tissues after they’re made. “We’re trying to make new surgical materials that can be applied more easily,” Kofinas says.

In particular, Kofinas is working with researchers at Food and Drug Administration and the Children’s National Medical Center, in Washington, D.C., on new surgical adhesives for sealing up blood vessels and intestinal tissue. Using sticky mats of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), or PLGA—a biodegradable, FDA-approved polymer—could prevent deadly leakages that require additional corrective surgeries.

Kofinas and his colleagues decided to adapt a process that’s been used to make polymer fibers in the lab, but not in the operating room: airbrushing, more commonly used to apply paint. They went to a hardware store and bought an airbrush, which uses compressed gas to push liquid from a reservoir through a nozzle. They then tinkered with different formulations of PLGA to find one that would work in the airbrush. By choosing the right molecular weight of PLGA and concentration of acetone as the solvent, they could control the diameters of the resulting fibers. They ended up producing mats with fiber diameters of about 370 nm. The Maryland researchers chose carbon dioxide as the compressed gas because it dissolves in blood and therefore has a low probability of producing deadly bubbles in a patient’s bloodstream, Kofinas says.

The researchers showed that the mats could seal diaphragm hernias and cuts to the lung, intestine, and liver in a pig. The acetone appears to evaporate before the nanofibers get deposited, suggesting that it won’t pose toxicity problems, according to the paper. Cells sprayed with the PLGA nanofibers show no change in health after 24 hours, and in lab tests, the nanofiber mats degraded completely over a 42-day period.

“Using an airbrush to deposit biomaterials directly onto tissue is quite enticing and has potential in many areas of medicine,” says Jeffrey M. Karp, a bioengineer and codirector of the Center for Regenerative Therapeutics at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, in Boston. Karp, who is also developing surgical adhesives, says the researchers need to study further the method’s safety, including how much acetone gets into the air of the operating room, since the solvent is flammable and can be an irritant.

Kofinas’s group is currently doing safety studies and improving the materials for surgical trials in animals.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter