Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Engineered Bacteria Ripen Fruit By Belching Ethylene

Bioengineering: Researchers program E. coli to produce ethylene, a gas commonly used by the food industry to ripen produce

by Erika Gebel Berg

November 25, 2014

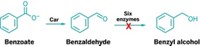

The ruby red rows of tomatoes at the local grocery store don’t come off the vine in such a pretty state. Food producers pick fruits while unripe and later douse them with ethylene, a gas that plants naturally produce to trigger ripening. The ethylene used by food producers comes from cracking fossil fuels. As a green alternative, Cristina Del Bianco of the University of Trento, in Italy, and her team engineered Escherichia coli to produce ethylene to accelerate fruit ripening (ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/sb5000077).

To program E. coli to make the gas, the scientists turned to another microbe called Pseudomonas syringae. This plant pathogen has an enzyme that converts 2-oxoglutarate, a citric acid cycle intermediate, to ethylene in a single step. The researchers inserted the gene into E. coli so that they could turn it on in the presence of the sugar arabinose. When they added arabinose to liquid cultures of the bacteria, ethylene levels in the flasks reached 100 ppm.

Next, the researchers grew the bacteria in flasks connected to jars filled with unripe cherry tomatoes, kiwis, or apples. After eight days, the fruits connected to flasks that received a dose of arabinose were significantly riper than those connected to bacterial cultures that didn’t get the sugar. The tomatoes were redder, the kiwis were softer, and the apples had less starch—a signature of ripening.

To make ethylene production easier for commercial applications, the team reengineered the bacteria so that they expressed the ethylene gene when exposed to blue light. The researchers detected 92 ppm of ethylene in a culture of these bacteria grown in blue light, whereas no ethylene was detected from bacteria grown in the dark.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter