Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Blood Protein Linked To Age-Related Memory Loss

Neuroscience: Finding ways to reduce levels of β2-microglobulin could lead to therapies to combat mental decline

by Michael Torrice

July 9, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 28

One frustrating part of getting older is memory loss—forgetting where you put the TV remote, not remembering the name of the family that used to live next door.

A new study in mice suggests that a protein that circulates in the blood and has levels that increase with age could be one culprit behind this mental decline. Finding ways to reduce the protein in the body could lead to therapies that prevent or reverse age-related memory loss, the researchers say.

“It’s a very impressive paper and a major advance in our understanding of cognitive aging,” says Scott A. Small, a neurologist at Columbia University who was not involved in the study.

The new work stems from a series of studies looking at molecules in blood associated with aging. Researchers, including Tony Wyss-Coray of Stanford University, have shown that transferring blood from young mice into old mice can reverse age-related loss in cognitive function. And the effect goes both ways: Blood from old mice can impair memory in young ones.

Saul A. Villeda, a former postdoc in the Wyss-Coray lab and now a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, wanted to study a blood factor implicated in those previous studies as contributing to the aging process—β2-microglobulin (B2M). Scientists have known that this protein plays a role in pruning nerve cell connections in young, developing brains.

In the new study, the researchers found that injecting B2M into the brains of young mice led to poor performance in tests of two types of memory compared with animals that didn’t receive the protein. But the effects weren’t permanent. If the researchers waited 30 days after the B2M injections and then ran the memory tests, the young mice showed no memory deficit.

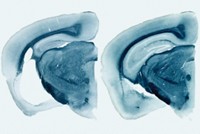

To determine the effects of removing B2M, the team engineered the mice to knock out the gene for the protein. With age, these animals showed less memory dysfunction than nonengineered mice of the same age (Nat. Med. 2015, DOI: 10.1038/nm.3898).

“The implication here is if you could reduce B2M in humans, you could reverse age-related memory decline, which would be profound,” Small says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter