Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Switzerland’s hidden pharmaceutical hub

Ticino blends Italian entrepreneurialism with Swiss efficiency

by Rick Mullin

October 31, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 43

The last hour of a train ride from Zurich to Lugano, Switzerland, is the best. As the train moves from the German- to the Italian-speaking region of the country, it ducks every few minutes into a tunnel through a mountain in the foothills of the Alps, emerging into a new Swiss vignette—a succession of quaint villages in valleys, each more enchanting than the previous.

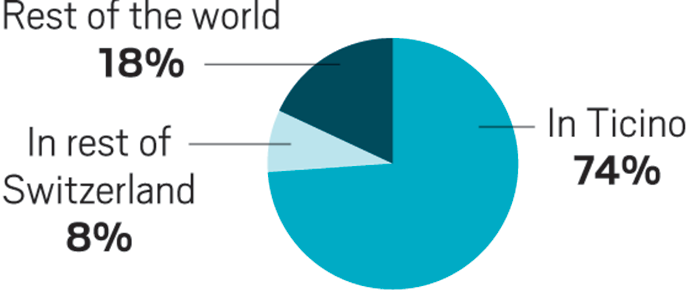

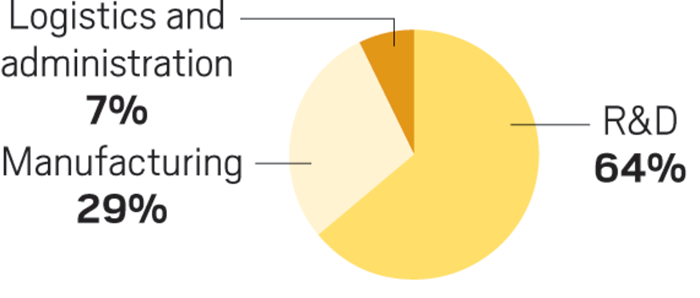

The drug companies of Ticino at a glance

▸ Number: 27

▸ Global employees: 2,500

▸ Total salary: $191 million

▸ Combined membership sales: $2.3 billion

▸ Investment forecast, 2016–18: $655 million

▸ Investment forecast in Ticino operations, 2016–18: $484 million

▸ Percent of regional industry sales: 38%

▸ Percent of Ticino gross domestic product: 8%

▸ Population of Ticino: 350,000

Note: The 27 drug companies are members of the trade association Farma Industria Ticino

Source: Farma Industria Ticino

Curved around the banks of Lake Lugano, the destination city is the largest in Ticino, the only wholly Italian-speaking canton of Switzerland. To the visitor, it seems to maintain a balance between a relaxed Italian culture and the watchlike precision and order of Switzerland as a whole.

That balance has helped nurture the region’s drug industry. Among the small businesses with factories nestled between Alpine foothills is a concentration of pharmaceutical activity mostly unknown to anyone outside Switzerland.

Basel, the northern Swiss town that is home to Roche and Novartis, is generally viewed as the country’s drug basket. But Ticino’s cluster of small providers of finished drugs, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), and services such as micronization and formulation should come as no surprise given the region’s link to Italy, which borders Ticino on two sides and has a heritage of pharmaceutical entrepreneurialism.

Some of the companies in Ticino are owned by Italian families. Others may have less direct links to the country across the lake, but their managers speak of strong ties, characterizing Ticino as a Swiss version of Italy with a business-friendly regulatory atmosphere.

Although pharmaceutical activity in Ticino can be traced back to the 1920s, the current landscape started taking shape in the 1960s, says Giorgio Calderari, chief operating officer of the drug company Helsinn and president of Farma Industria Ticino (FIT), a 27-member industry association. Contours were added in the 1970s, when Italy endured years of political and social unrest.

A “new generation” of business leaders followed in the 1980s, many with experience working for Italian drug companies, Calderari says. “They were entrepreneurs looking for a more stable and better place to do business.”

Calderari refers to Ticino as a kind of virtual company of 2,500 employees that exports 85% of its output. Meeting with C&EN at an FIT booth at the CPhI Worldwide pharmaceutical ingredients exposition in Barcelona this month, he pointed out association members’ booths in the surrounding area. For the past three years, FIT has corralled companies that previously were spread out across the event’s six to eight exhibition halls.

As part of its effort to promote Ticino as a high-tech pharmaceutical services hub, FIT works with the University of Applied Sciences & Arts of Southern Switzerland and the Swiss Institute for Research in Biomedicine, which specializes in cancer research. The schools provide training and consultation. Ticino also has a technology park, the Agire Foundation, established to foster technology entrepreneurs.

But as the group tries to mold a more recognizable regional identity, many companies in Ticino are branching out, Calderari says, acquiring operations elsewhere in Europe and partnering with research and manufacturing organizations as far away as Texas.

Helsinn, for example, recently formed an alliance with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston under which it will support early-stage clinical trials. At home, the firm is investing about $20 million to expand its anticancer API facility with three plants ranging from 20 to 800 L in annual production capacity and a chromatography unit for purification.

Helsinn is owned by the Braglia family, which opened a small pharmaceutical company near Milan shortly after World War II. The family decided on Ticino as a site for a new drug licensing venture in the 1970s. Initially called Biex Solaris, the venture worked with Italian contract manufacturers on projects including Wyeth’s anti-rheumatism drug fentiazac, for which it developed a route to the API.

The family elected to pursue contract manufacturing on its own, building its first API plant in Ticino in the early 1980s. Helsinn had its first big success 10 years later with the cancer compound palonosetron, which it licensed from Hoffmann-La Roche and turned into its first drug launch in the U.S.

The firm was also a pioneer in developing international operations. In 2009, for example, it purchased New Jersey-based Sapphire Therapeutics to access R&D and production capabilities. That year it also launched Helsinn Birex Pharmaceuticals, an Irish solid oral dose maker.

Helsinn is unusual among Ticino firms in the way it straddles innovative drug development and contract manufacturing. More typical is the nearby contract manufacturer Cerbios-Pharma, which was started by a local pharmacist in 1931 as a drug wholesale operation. In the 1970s, it expanded into fermentation, pollen extract, and pharmaceutical chemical businesses. The three were merged to form Cerbios in 1994.

The company is still family-owned, managed by the third-generation members of the two founding families, according to Chief Executive Officer Gabriel Haering. Formerly the head of business development for Helsinn’s chemical operations, Haering joined the company in 2009.

In recent years, the company has struck up product development partnerships with two firms outside of southern Switzerland. Two years ago, Cerbios announced an agreement with Sweden’s Lipidor to develop dermatological products based on Lipidor’s technology. Cerbios also formed an R&D partnership with Chemelectiva in Novara, Italy, which effectively doubled the company’s in-house research staff of 20, including 12 chemists.

Earlier this month, Cerbios joined a four-way antibody-drug conjugates partnership called Proveo that includes Denmark’s CMC Biologics and IDT Biologika and Oncotec Pharma Produktion, both of Germany. CMC produces monoclonal antibodies; Cerbios provides process development, manufacturing of the cytotoxic drug-linker combination, and conjugation to the antibody; Oncotec provides aseptic filling and freeze drying; and IDT performs analytical and quality services and packaging.

According to Haering, Cerbios’s Swiss identity is important. “We try to bring sophistication,” he says, referring to the high-tech chemistry the country is known for. Swissmedic, the pharmaceutical regulatory authority in Switzerland, is cooperative with industry. And the family owners are committed to the company. “They aren’t looking out to 2020; they are looking out to 2030,” Haering says. “They are committed to investing for growth.”

Sales at Cerbios reached $36 million last year, and Haering expects double-digit growth in 2016. “This is the best year ever for the group,” he says.

Generic drug producer Rivopharm is among the companies that came to Ticino in the 1960s. It has international roots, however, having been launched in 1961 by the Lebanese entrepreneur Kamal H. Ghazzaoui. In 2005, it was acquired by Piero Poli, whose family owned a drug company in Milan that Searle acquired in 1998.

More recently, Rivopharm acquired Germany’s Holsten Pharma and launched a drug development subsidiary in Ticino called Developharma. Since he acquired the company, Poli says, staff has grown from 45 to 170. It currently can turn out about 2 billion capsules and tablets per year.

Poli emphasizes that the firm is not “Swiss-oriented.” It exports 95% of its production, and 60% of the company’s workforce lives in Italy.

In contrast, the oldest pharmaceutical company in Ticino, Sintetica, has remained small and focuses mainly on the Swiss market of about 8 million people, according to President Luca Bolzani. Founded in 1921, Sintetica manufactures hospital anesthesia and pain management drugs.

Bolzani and financial partners purchased the company in 2000. “We were certain of the value of the company, given its long history and good management,” Bolzani says. Its leadership position in the Swiss market was also attractive. “We saw the potential of a company that had not exported an ampule,” he says.

The firm does, however, have manufacturing outside of Ticino in Neuchâtel in the French-speaking region of Switzerland. And it is beginning to look beyond the Swiss border entirely. The company is now selling directly into Austria, Germany, and the U.K., in addition to selling elsewhere through distributors. Exports have risen from 5% of sales to 40% in just two years.

Bolzani says he expects sales to hit $50 million in 2016 and turnover to double in five years with exports reaching 70%. The key will be to maintain the quality of the company’s products, which he says can only be done by operating in Switzerland.

Other firms in the region are more specialized in their products and services. Linnea, established 36 years ago by an Italian chemical engineer, manufactures botanical extracts and APIs for pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and cosmetics. It has patented products from a range of plants, including cannabis, red clover, and bilberry, the latter being the source of an API that treats menopause symptoms. The company also extracts butylscopolamine, an active pharmaceutical ingredient used to treat abdominal pain.

Linnea, which markets outside of Switzerland through distributors, came to Ticino for the same reason as other companies with Italian roots—the growing focus on pharmaceuticals and the high level of technology that characterizes science and manufacturing in the region, General Manager Christian Beltrametti says.

Beltrametti laments that expansion in Ticino is constrained by the cost of land and construction compared with the regions with which it competes. “We have a chance to grow, but it’s not unlimited as it would be in China,” he says. The company has annual sales of about $45 million.

Micro-Macinazione, a specialist in micronization for reducing particle size, came to Ticino at about the same time as Linnea. The firm, formed as an engineering company, also designs and supplies equipment such as mills and isolators. In 1990, Micro-Macinazione shifted its focus to micronizing APIs to boost their solubility, according to Chairman Martin Riediker. A second plant was opened in 2000 and an R&D facility was added in 2015, he says.

The company has also steadily expanded its market. “At the beginning, the company focused only on Ticino and northern Italy,” Riediker says. “We are now the leader for micronization in Europe, producing more than 1,000 metric tons of APIs per year.” The company is building a $2.5 million warehouse and is increasing its work in high-potency APIs.

Micro-Sphere, founded in 1998 by Michele Müller, a University of Bern chemist, offers an alternative to micronization for improving API solubility, according to CEO Stefano Console: particle engineering and spray drying. The company works mainly with European customers but received its first U.S. Food & Drug Administration inspection in 2013, opening the U.S. market. It is building a finished-dose capsule facility.

In addition to its business and science benefits, Ticino offers an “ecosystem” of product and service providers that spans the pharmaceutical supply chain, Console says. “People don’t realize that within a 30-minute drive you can find a number of companies involved in micronization, API, small molecules, large molecules, extracts, regulatory services. Except for in America, that’s quite unusual. And that ecosystem is increasingly connected with the global market through partnerships.”

An interesting new niche in the ecosystem may be in the offing. Synchro Morph Solutions, created in January, plans to analyze APIs’ multiple crystal forms in Ticino using data collected at a synchrotron in Trieste, Italy. Building on a technology developed at the Italian drug maker Zambon, which has an operation in Ticino, Synchro Morph will initially focus on offerings such as particle analysis services for inhalable drugs, says Livius Cotarca, the firm’s chief scientific officer.

Cotarca, formerly head of R&D at Zach System, a division of Zambon, hopes to open a lab in Ticino in 2017. Inhalation drug services “are very big here,” he says. “We are close to an agreement with a company in Ticino to receive samples and prepare them for analysis.”

As the region’s pharmaceutical industry enters a new, more global phase, managers of Ticino-based companies say there is a commitment to sustaining its science and business culture. And as with any ecosystem, sustainability is a primary concern for the Swiss pharmaceutical hub.

“The world is our market, but we have to keep the Ticino identity, one that our community can be proud of and sustain ourselves,” Helsinn’s Calderari explains. “We need to act globally, but it’s really important that the community thinks of itself as a local entity.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter