Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Consumer Products

Newscripts

Blue film and pink waves

by Sydney Smith

June 11, 2023

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 101, Issue 19

Happy accident brings the blues

Leafing through a dusty stack of Polaroids can be nostalgic—and maybe bring a hint of blues. In a fitting bit of serendipity, early-career chemist Brian Slaghuis accidentally discovered a new type of Polaroid film, and it’s blue.

Dubbed Reclaimed Blue, the film was born at the last remaining Polaroid film factory, in the Netherlands. This unintended invention, released in April, was sparked by an assignment to use out-of-specification materials. Slaghuis got to work with an open mind.

The film is made of three layers: sheet, negative, and paste. The sheet layer caps the reactions. The negative layer has light-sensitive silver halide crystals, which capture a sort of shadow of the image, and dye developer sublayers. These are cyan, magenta, and yellow in color film. The paste layer, holding the film developer, lives within the iconic wider part of the photo frame and is squeezed out when exiting the camera.

Venturing into the unknown, Slaguis invited strangers—the developers for color film and for black-and-white film—to mingle. The latter is tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ). These differing chemicals aren’t usually mixed, but the chance encounter inspired new hues.

Just how did this mixture bring blues where no dyes were added? The guess is that TBHQ in the black-and-white film directs the color film to allow cyan to step on stage and sing the blues, while the other colors sit quietly in the audience. If that explanation is chemically unsatisfying, Slaghuis says in a statement, “it may take 10–15 years of research to fully understand it.”

Innovation touching art and science is key for Polaroid. The company’s cofounder, Edwin Land, developed the idea for the first instant film camera in 1943, after his daughter asked why she must wait to see the photo he had just snapped on a family vacation.

Also in the “why not?” vein, Slaghuis had an artful accident when he created Reclaimed Blue, building on the joys of both chemical discovery and instant photography—even if blue.

Pink plumes’ passage

While Reclaimed Blue was created at the interface of chemistry and photography, pink plumes rolling off the coast of Southern California play within the interface of land and ocean.

Sarah Giddings, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, heads the endeavor colorfully called PiNC, or Plumes in Nearshore Conditions, which began early this year.

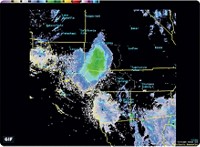

The point of PiNC is to track where pink-dyed estuary plumes at Los Peñasquitos Lagoon, in San Diego, land after surfing toward the breaking waves. For instance, can the plumes charge through and hang 10 on their way to the open ocean, or do they wipe out and become trapped along the coast, where people recreate? The freshwater carries with it nutrients, sediments, larvae, and, unfortunately, pollution.

A master of fluid mechanics, Giddings is stoked to develop a better understanding of the fundamental physics governing how plumes make their way out of smaller coastal estuaries. Her team isn’t just hanging loose, though. They successfully conducted three dye releases, during which they poured about 57 L of the fluorescent pink water tracer Rhodamine WT into the estuary mouth. Cool tools like a hyperspectral camera mounted on a drone and fluorometers on a jet ski tracked the tracer’s movement.

But why pink? Giddings points out that only two dyes have been approved for this sort of use. One is pink, and the other is yellow—and as many sly swimmers know, yellow disappears in the water.

Preliminary results indicate more plume trapping than expected, Giddings told Newscripts in an email. More information about estuary movement could point swimmers and surfers to a safer place to play during times of gnarly water trapping.

Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter