Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Food Science

Newscripts

Chemists who cook share discoveries and memories

by Sam Lemonick

January 10, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 2

This chemist really blue it

Lots of people make something special for a holiday meal. Maybe it’s Grandpa’s twice-baked potatoes or a pecan pie you saw on Instagram. For Dani Schultz, the twist this Thanksgiving was blue garlic. She didn’t plan it, but she did solve the mystery of how it happened.

Schultz, a Merck & Co. process chemist, had prepared a brine for her turkey: water, salt, herbs, lemons, oranges, and crushed garlic brought to a boil. When she lifted the lid and stirred the mixture, she realized her garlic had turned blue. Neither she nor her husband had seen or heard of anything like it before.

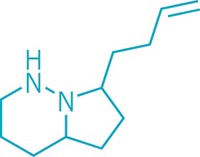

So, as one does, she went to the scientific literature. There she found an explanation from Shinsuke Imai and colleagues at House Foods (J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, DOI: 10.1021/jf0519818). Schultz tells Newscripts that the chemical that gives garlic its smell, allicin, reacts in the presence of an acid (in this case, from the citrus fruits) with amino acids to form five-membered pyrrole rings. When several pyrroles bind together, the result is blue pigments.

She also learned that the reaction—or, at least, its azure effect—is well known to many. After she tweeted a picture of her garlic (shown here) and a figure from Imai’s paper, chemist Tianfei Liu of the State Key Laboratory of Elemento-organic Chemistry and Nankai University mentioned blue-green Laba garlic, pickled in vinegar and eaten on some Chinese holidays.

Schultz isn’t sure she’ll make blue garlic again, but she hopes others will, maybe as a way to show kids some cool food chemistry. Her tip: crush the garlic to break cell walls and release the enzymes that facilitate the reaction.

Bite-size memories

Cooking, chemistry, and Twitter intersected in a different way for chemist David K. Smith of the University of York. His new cookbook—a first for him—is Tw-eat, which Smith describes as a cookbook and a memoir.

The project started as a collection of recipes for the family of his late husband, Sam, and for Smith and Sam’s son. Smith picked meals that had some memory of Sam, whether it was a simple weekday supper or a dish they shared on a special vacation.

Each page of the cookbook pairs a simplified recipe with an explanation of the food’s emotional resonance and a photo of the dish. Smith had already shared many of these recipes and photos on Twitter, so he borrowed the site’s conceit: almost all the recipes fit within 280 characters, more or less.

That limit required some concessions. The recipes tend to include only bare-bones instructions. Smith says they’re more like templates, which, along with the photo, will give people enough information to make the meals on their own. Others stretch into two or three tweet-length chunks. Smith tells Newscripts that his years of writing synthetic procedures in lab notebooks were good practice in brevity.

Some recipes are not exactly recipes. “Sam’s Mexican Fish Stew” was one of the last things he cooked for Smith. “I remember it tasted absolutely delicious.” Trying to re-create Sam’s recipe might not match the way Smith remembers it, so he simply includes the ingredients and a photo. Smith hopes readers will find their own ways to make the stew and other recipes and to make these dishes their own.

Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Correction

This story was corrected on Jan. 12, 2021, to reflect that most recipes in David K. Smith's book Tw-eat do specify quantities of ingredients, but the book does not contain detailed instructions typical of most cookbooks.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter