Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Delivery

Light-activated naloxone may protect from opioid overdose

If it works in people, the new formulation may offer those at high risk of overdosing immediate access to the medication

by Alla Katsnelson, special to C&EN

November 22, 2023

More than 100,000 people in the US died after overdosing on opioid drugs last year, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. Naloxone, a potent opioid antagonist, swiftly reverses overdoses by binding to the same receptors that opioids bind to, thereby crowding out opioid molecules. Despite naloxone coming in easy-to-administer nasal sprays, people experiencing an opioid overdose often don’t have access to the life-saving drug at the crucial moment when they need it. Now, researchers have created an inactive version of naloxone that can be administered to someone at high risk of overdosing, and then when naloxone is needed, it can be activated with a burst of blue light (ACS Nano, 2023, DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c03426) .

Daniel S. Kohane, a biomaterials scientist and anesthesiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School who led the work, envisions that people who receive such an injection would also carry the light source, perhaps in the form of something like a medical bracelet. “The irradiance that we use is about 100 times ambient light,” Kohane says, so the risk of activating the naloxone accidentally is low. What’s more, he says, the injection site could be covered to prevent that possibility.

The modified naloxone has so far been tested only in mice. But if it works in people, it may be an important addition to the existing options, which must be administered after a person has an overdose, says Kohane, who routinely uses naloxone in the emergency room to treat overdoses and to reverse anesthesia after surgery.

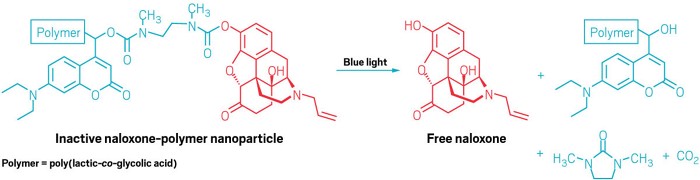

To make the molecule, he and his colleagues started with poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), a biodegradable, biocompatible polymer widely used for drug delivery. To each end of the PLGA they bound a naloxone molecule, attaching it with a light-sensitive linker designed to be cleavable with 400 nm (blue) light.

The researchers injected these molecules, formulated as nanoparticles, under the skin of mice who had been given a dose of morphine. Shining a blue light on the injection site for 2 min released the naloxone molecules from the linker, allowing it to circulate throughout the body and reverse the effect of the morphine.

They were able to activate the naloxone for about a month after the mice received the injection, and during that period they could activate it about three times. Kohane and his team plan to create longer-lasting versions of the drug, as well as ones that can be activated more than three times. They also plan to investigate how it scales from a mouse’s 25 g body to an adult human’s 75 kg one.

Although the light activation system is “interesting,” says Thomas Kosten, a psychiatrist and pharmacologist at Baylor College of Medicine, it may not be realistic to expect someone experiencing an overdose to activate it or to tell others to do so. “I do not see a practical clinical application of this technology,” says Kosten.

But Sharon Levy, an addiction medicine specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital who was not involved with the work, says that although it won’t be for everyone, the approach may be important for people at especially high risk of overdose. “The problem of opioid overdose is so deep that I think we are going to need to combine all kinds of solutions,” she says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter