Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Food Ingredients

Forensic Science And The Innocence Project

A symposium at the ACS meeting illuminates challenges for and rifts in the justice system

by Carmen Drahl

September 10, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 37

Steven Barnes’s truck was muddy. As he pulled up on a September day in 1985 to a roadblock for what he thought was a routine traffic stop, the dirt was close to the last thing on his mind. But the mud caught the attention of local police officers in Barnes’s small, upstate New York town. They were investigating the rape and murder of high school student Kimberly Simon, whose body had been found days before, on the side of a muddy dirt road. Barnes, 19, went to the station for more than 12 hours of questioning. He explained to investigators he’d been at a local bowling alley at the time of the murder. He gave police permission to search his truck and figured that was that. Then, two years later, investigators asked Barnes for blood, saliva, and hair samples.

COVER STORY

The Case Of Forensics

Barnes was arrested in 1988. At his trial, forensic experts testified that soil, hair, and an imprint from denim on his muddy truck matched samples from Simon. It proved a convincing combination to the jury, along with vague statements from eyewitnesses and a jailhouse snitch. In June 1989, Barnes was convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

From his cell in 1992, Barnes wrote a letter to a new legal organization he hoped might set him free. That organization, called the Innocence Project, agreed to take his case in 1993.

The Innocence Project is a nationwide legal network that works to exonerate innocent prisoners through DNA testing. Experts agree that the Innocence Project has changed the justice system for the better, both by freeing the innocent and by encouraging scrutiny of all types of evidence presented in the courtroom.

It is perhaps the most visible player in a movement that is challenging improper use of forensic science in the legal system. That role has led to tensions with some members of the forensic science community, who are concerned that the criticism of crime labs that has emerged is unfairly broad. In an effort to spark a dialogue with chemists and rally them to the cause, the Innocence Project held a symposium at last month’s American Chemical Society national meeting in Philadelphia. The session highlighted challenges in forensic science as well as forensic techniques that lack scientific vetting.

Before the Innocence Project existed, says Peter M. Marone, director of the Virginia Department of Forensic Science, “was the little guy getting a fair shake? No.” The organization’s efforts to free its mostly destitute clients date to 1992, when attorneys Peter J. Neufeld and Barry C. Scheck, both members of O. J. Simpson’s defense team, established the Innocence Project as part of Yeshiva University’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Since its founding, the Innocence Project has had a hand in nearly 300 exonerations.

One of those exonerated is Ray Krone. An honorably discharged veteran, Krone served 10 years “in a cell the size of most of y’all’s bathroom,” he said in Philadelphia, for a murder in Phoenix he did not commit. An expert for the prosecution had testified that bite marks on the victim matched an impression Krone made for police on a Styrofoam cup. With help from the Innocence Project, DNA evidence cleared him in 2002. “I can’t tell you what it was like to be called a monster,” he said. “Thank God for DNA.”

It was DNA that made the Innocence Project possible, says chemist Jay A. Siegel, a longtime forensic scientist and adjunct professor at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. The technology matured in the academic community, and if used properly, makes it possible to link an individual to evidence such as bloody knives or semen-stained clothing. The absence of DNA doesn’t always mean a person is innocent, so DNA alone isn’t enough to solve a crime, Siegel cautions. “That’s a myth perpetuated by ‘CSI,’ ” the popular TV show.

What’s more, some types of DNA technology have shortcomings, as Boise State University geneticist Greg Hampikian cautioned Philadelphia meeting attendees. Sample collection methods haven’t changed since DNA’s courtroom debut in the 1980s, even though assay sensitivity has increased dramatically, he said. His group has shown that detectable amounts of DNA can transfer between specimens if a handler forgets to change gloves. Hampikian, director of an Innocence Project affiliate in Idaho, also showed that if exposed to extraneous details about a case, experts can give very different interpretations when analyzing DNA mixtures, as can appear in cases of gang rape (Sci. Justice, DOI: 10.1016/j.scijus.2011.08.004). Despite these caveats, DNA testing is the gold standard among forensic disciplines, because it has undergone thorough scientific vetting.

Other forensic tests lag behind DNA in several ways. These tests include fingerprinting, as well as the hair, soil, and denim imprint analysis used in Barnes’s trial, and the bite-mark analysis from Krone’s trial. They cannot point to an individual, and little to no research has been conducted toward standardizing them or defining their error rates. Problems arise when attorneys, judges, or juries attach the same aura of reliability to all forensic sciences regardless of their scientific merit, says attorney Josh D. Lee, cochair of the Forensic Science section of ACS’s Division of Chemistry & the Law and coorganizer of the Philadelphia session.

To John J. Lentini, arson investigation is a particularly troubling example. Much of the field has been “witchcraft that passes for science,” he said in Philadelphia. Lentini, a fire investigator, discussed the 1980 “Fire Investigation Handbook,” which codified unwarranted generalizations. It was published by the National Bureau of Standards, the agency that predated the National Institute of Standards & Technology. The book associated irregular cracks in glass—called crazed glass—with rapid heating, which suggests the use of fire accelerants. It also stated that narrow V-shaped char patterns on walls indicate fast-developing, hot fires. These myths, as Lentini called them, were once considered scientific fact in courtrooms. As an example, Lentini said, they were cited in the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, a Texas man executed in 2004 for setting an arson fire that almost certainly wasn’t arson.

V-shaped patterns, as research from Lentini and others shows, can occur in fires set accidentally, not just arson fires. Crazed glass actually forms during rapid cooling, such as when fires are put out, not during rapid heating. The National Fire Protection Association has published scientific-based guidelines for arson investigations since 1992. But Lentini cautioned that misperceptions still abound.

Traditional forensic science got grandfathered into the justice system, says Carrie Leonetti, an attorney who has served on the American Bar Association’s Task Force on Biological Evidence. “It’s a lot harder to ask a court to exclude evidence that has been admitted for a hundred years than to exclude evidence it’s never seen before,” Leonetti, of the University of Oregon School of Law, explains. “Because DNA was so new, it went through incredible vetting.” That didn’t happen for other forensic disciplines, she adds.

As courts became willing to consider DNA technology, it enabled unprecedented reanalysis of old cases. The first DNA exoneration took place in 1989, just three years before Barnes contacted the Innocence Project from prison. In 1996, the Innocence Project obtained DNA test results on old evidence from the 1985 crime scene. DNA tests conducted before Barnes’s trial had been inconclusive. This second round came back inconclusive again. It would take more than a decade before scientific advances would give Barnes another chance.

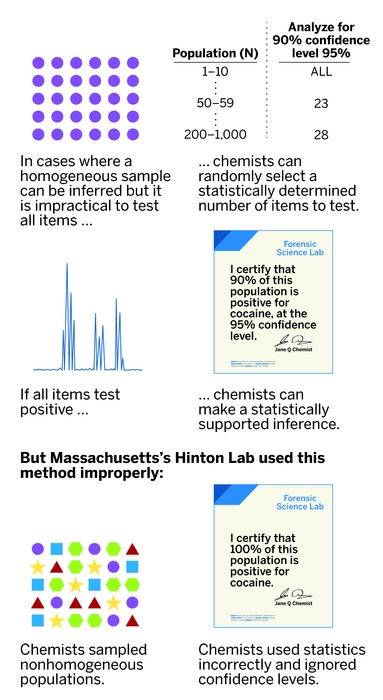

Research conducted by the Innocence Project suggests that the number one contributor to wrongful convictions is eyewitness misidentification. But number two, involved 45% of the time, is faulty forensics, which the Innocence Project defines as testimony that isn’t scientifically vetted, exaggerated testimony, and forensic misconduct.

In Philadelphia, Frederic W. Whitehurst, a Ph.D. chemist and former supervisory special agent at the Federal Bureau of Investigation Laboratory, discussed a colleague’s false or misleading forensic testimony in multiple cases. He also described how scientists would “run dead flat into a sledgehammer” when their results didn’t agree with their supervisors’ thinking. Whitehurst’s whistle-blowing led to a 1995 Justice Department investigation of the FBI Lab.

The institutional pressure Whitehurst experienced is not the norm, says José R. Almirall, a forensic scientist who worked for the Miami-Dade Police Department Crime Laboratory before becoming director of the International Forensics Research Institute at Florida International University. “In the 12 years I worked at a police agency, I never felt in any way forced to opine in one way or another.”

Nor is exaggeration or falsification of forensic testimony commonplace, adds Philadelphia Department Police Forensic Services Bureau chemist David J. Wolf. “We don’t say whatever we feel like in court,” he says. “We have mock trials within our laboratory to teach new chemists how to go about testifying. It takes years to learn how to testify really well.”

Wolf, who was in the audience in Philadelphia, says he felt wounded by the session. Attendance in the vast ballroom was sparse, but a handful of people, including Wolf, asked pointed questions. “It was the only lecture I’ve ever been to where I felt like I was being torn apart.”

The long-festering wound for forensic scientists is the Innocence Project’s 45% figure, which they argue is unfairly high. “I think the Innocence Project underestimates bad lawyering as a cause of wrongful convictions,” Siegel says. Prosecutors may withhold evidence that could exonerate a defendant, and defense teams may not be trained to mount an argument against inappropriate testimony, he explains.

When DNA evidence overturns a conviction, that doesn’t necessarily mean a forensic scientist was doing bad work, adds Thomas A. Brettell, a forensic chemist at Cedar Crest College who retired from the New Jersey State Police Office of Forensic Sciences in 2007. Before DNA, no way existed to definitively link an individual to evidence, he says, and the vast majority of experts interpreted results in good faith.

“Where the Innocence Project lost credibility with me was in trying to put blame squarely on the shoulders of forensic science,” says John M. Collins, emeritus Forensic Science Division director for the Michigan State Police. “There are some practitioners who don’t do a very good job in the courtroom, but that shouldn’t be an indictment of the science.”

Collins copublished a report that puts the percentage of exonerations involving faulty forensics closer to 11%. The criticisms of forensic techniques have been published in law reviews, not peer-reviewed scientific journals, Collins says. Forensic experts’ opinions, he says, should be good enough.

That’s not good enough, Whitehurst argues. A 1993 Supreme Court decision in ruled that forensic evidence at trials must be validated and subject to peer review in the scientific community, with known error rates and appropriate controls. A set of opinions, even expert opinions, doesn’t amount to science, he adds.

Determining what contributes to wrongful convictions is more complicated than assembling a list of percentages, social scientists say. Considering only erroneous convictions is a recipe for selection bias, explains statistician Russell V. Lenth of the University of Iowa, who studies forensic science. “We can’t make claims about all lawyers, or about all forensic scientists, based only on cases where one or both of these groups failed.”

Whitehurst acknowledged this complexity in Philadelphia. “We stand here in judgment of forensic science labs,” he said. “But this is a bigger problem than just crime laboratories. This is a social problem.”

Social pressures outweighed forensic evidence in the case of Raymond Santana. He and four others, all young teenagers, went to jail in 1990, convicted of raping and assaulting a New York City woman in the infamous “Central Park jogger case.” DNA evidence existed that pointed to the teens’ innocence, but under intense media scrutiny, police and prosecutors “made up their minds we were guilty, and that was it,” Santana said in Philadelphia. It wasn’t until the real perpetrator, a serial rapist, came forward, and DNA confirmed his involvement, that Santana and the others were exonerated. After a five-year jail term, Santana had a difficult time adjusting, turning to selling drugs for a time. He thanked forensic scientists for securing his freedom. “Without you,” he said, “I wouldn’t be able to be talking here today.”

Advertisement

In Philadelphia, Innocence Project cofounder Neufeld asked ACS members to get involved in developing standards for forensic science. He also urged ACS to stand behind two bills making their way through Congress that would mandate changes to how forensic science in the U.S. is funded, organized, and regulated. Forensics have been in the federal limelight since a 2009 National Research Council report found much of the science in crime labs wanting (C&EN, June 25, page 32).

In an interview with the Innocence Project three months after his release from prison, Barnes recalls the day he learned he would be freed and reflects on the meaning of freedom.

Change is going to take time for forensic science, says Cedar Crest’s Brettell. “Everybody has the same goals in mind,” he says. But the legal community and the crime labs “are coming from two different directions.”

“It’s a big cultural divide,” and a great amount of training must take place, Brettell adds. “That’s not going to happen without resources and understanding.”

Barnes served more than 19 years in prison before DNA technology could be brought to bear on his case. In 2008, a test of short tandem repeats on the Y chromosomes of sperm found on the victim showed that Barnes wasn’t a match.

He returned to a world that seemed to have moved on without him. “I didn’t know what the Internet was, what a cell phone was,” he said in Philadelphia. Now a free man, he said he’s passionate about his new purpose—speaking on behalf of the Innocence Project around the country.

“I am trying to dedicate my life to the Innocence Project,” he said. “They gave me my life back.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter