Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Food Ingredients

FDA homes in on harmful chemicals in food

Agency seeks to overhaul food program with new emphasis on chemical risks

by Britt E. Erickson

July 16, 2023

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 101, Issue 23

For decades, the US Food and Drug Administration has focused its food safety efforts on microbial pathogens that cause food-borne outbreaks. Preservatives, colors, and other chemicals that are added to food have taken a back seat.

But the agency is facing a flood of petitions to ban chemicals like titanium dioxide, Red No. 3 dye, phthalates, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in food and food packaging. It’s struggling to keep up with the requests from advocacy groups and Congress and wants to move away from this reaction-based approach to a more preventive way of addressing the health risks of food chemicals.

As part of a proposed reorganization of its Human Foods Program, the FDA is seeking to do more to manage the risks of the 10,000-plus chemicals added to food and food packaging. But that will require funds the agency doesn’t currently have.

The proposed change comes during a particularly tough time for food safety at the FDA. Its top two food program directors stepped down earlier this year after a scathing report in December 2022 by an expert panel convened by the Reagan- Udall Foundation and criticism about the FDA’s response to the national shortage of infant formula last year.

Both the Reagan-Udall evaluation, conducted at the request of FDA commissioner Robert Califf, and the agency’s own internal review of the infant formula crisis pointed to serious shortcomings in its food safety culture and structure. The findings “also noted several areas of need, including modernizing data systems, providing more resources and authorities, improving emergency response systems, and building a more robust regulatory program,” Califf said in late January, when he announced the agency’s intent to overhaul the Human Foods Program.

Under the plan, the FDA will combine the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), the Office of Food Policy and Response, and parts of the Office of Regulatory Affairs under one leader, who will report directly to the commissioner.

The deputy commissioner for human foods will oversee all the FDA’s nutrition and food safety programs, including inspections, laboratory testing, and efforts to get a better handle on chemical risks. Oversight of cosmetics and coloring agents will be moved under the Office of the Chief Scientist.

In an updated plan released June 27, the FDA proposes making microbial and food chemical safety separate offices; the vetting of dietary supplements and innovative food ingredients would be housed with food chemical safety. The agency also wants to create a specific office for risk prioritization and surveillance.

All this will require money and people, which the agency doesn’t have a surplus of.

“One of the most eye-opening pieces of information that came out of the Reagan-Udall Foundation study was the relatively flat funding” for the FDA office that reviews food chemicals, Steven Musser, CFSAN’s deputy center director for scientific operations, said in a keynote address at a June meeting of the Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS).

The number of FDA employees reviewing the safety of food additives and food contact substances has not changed significantly in the past 40 years, despite a growing number of reviews, Musser pointed out. Agency staff now review biotechnology-based foods, recycled materials, a host of new food dyes, and an avalanche of citizen petitions to ban harmful chemicals in food, he said.

With limited staff and funding, the FDA is seeking to prioritize which of the thousands of chemicals in food and food packaging it should evaluate for potential safety risks. “We can’t sample everything,” Musser said. “We can’t test everything.”

Artificial intelligence is likely to play a role in that prioritization process. The FDA hopes to get extra funding in fiscal 2024, which begins Oct. 1, to upgrade its information technology infrastructure. It is developing computer models to help sift through extensive amounts of data and prioritize chemicals as high, medium, or low risk. If the agency gets the additional funding, Musser said, “we’re going to automate the whole system and hopefully make it available to the public to do their own analysis.”

The big question is whether Congress will give the FDA extra money for food safety. A deal reached May 31 between President Joe Biden and Speaker of the House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy to raise the US debt limit essentially froze federal budgets for the next 2 years.

Industry-paid user fees are not an option unless Congress authorizes the FDA to collect them from food manufacturers, and congressional action doesn’t appear to be on the table. Unlike other parts of the FDA, which rely heavily on user fees to review the safety of new drugs, medical devices, and tobacco products, the food side gets most of its resources from the federal budget.

“Appropriations seem to be getting cut kind of across the board,” says Melanie Benesh, vice president of government affairs at the Environmental Working Group (EWG), an advocacy organization. But the FDA has identified food safety as a priority, “and the food industry would like to see more funding go to the FDA foods program because they also suffer when the FDA lacks credibility.”

The FDA is already actively reviewing the safety of about 10 chemicals, says Tom Neltner, senior director of safer chemicals at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). The agency should figure out how to fix the system for reevaluating those chemicals in a timely way “because the track record is not great,” he says.

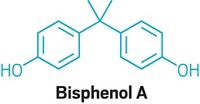

The FDA often misses deadlines to respond to petitions to ban chemicals in food or food packaging, Neltner says. The EDF is currently waiting for responses to its petitions to ban Red No. 3, titanium dioxide, bisphenol A, phthalates, lead, and PFAS in food or food contact materials, he says. Some of the petitions are more than a year old.

The EDF and other groups filed the phthalates petition in 2016, and the FDA denied it in 2022. The agency then agreed to reconsider the petition at the groups’ request. That decision is pending.

The FDA has been evaluating the safety of the preservatives butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) for 33 years, Neltner says. The agency is also scrutinizing brominated vegetable oil and propylparaben, he adds.

Benesh at the EWG agrees that the FDA should not make prioritizing chemicals for reassessment overly complex. She and other environmental and consumer advocates are generally optimistic about the agency’s intention to overhaul food safety related to chemicals, but they warn the FDA not to get too bogged down with fancy AI systems. “My understanding is that they’re working on a very complicated decision tree and process,” she says. “And I’m not sure that’s necessary.”

Benesh points to five chemicals that would be banned under California legislation (A.B. 418) that passed the assembly in May and is now being considered in the state senate. Those five chemicals—brominated vegetable oil, potassium bromate, propylparaben, Red No. 3, and titanium dioxide—as well as chemicals banned in other countries and those subject to petitions would be a good place to start, she says.

Another place to look is the Food Chemical Reassessment Act of 2023—a bill reintroduced June 7 in the US House of Representatives by Reps. Jan Schakowsky and Rosa DeLauro, Benesh says. The bill would require the FDA to evaluate the safety of at least 10 chemicals in food or food packaging every 3 years, starting with tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ), titanium dioxide, potassium bromate, perchlorate, BHA, BHT, brominated vegetable oil, propylparaben, sodium nitrite, and sulfuric acid. The bill would also bring back an external food advisory committee to inform the FDA on evaluation methods.

The FDA reviewed the safety of many food chemicals decades ago, and it doesn’t have a process to reassess them when new science arises. In addition, the agency has never reviewed thousands of chemicals in food because industry deems them generally recognized as safe (GRAS). Consumer advocacy groups are urging the FDA to revise the GRAS process.

“The FDA should be monitoring what’s coming into the food supply,” Benesh says. “And the FDA should have much more stringent controls rather than just letting industry self-refer whatever kind of chemical they want to as GRAS.”

The FDA’s Musser defended the GRAS process when asked at the IAFNS meeting whether the agency had plans to revise or eliminate the approach. “If there were a GRAS substance that we needed to take action on, given the current state of our legal framework for reviewing these, we could remove a GRAS substance very, very quickly, whereas a food additive could take decades,” he said.

Advocacy groups are also pushing the FDA to consider all health effects, not just cancer. “The FDA theoretically looks at all of them,” Neltner says. But it tends “to only look at things that are proven to cause harm in a demonstrable way,” he says. The agency also tends to dismiss epidemiology studies in favor of animal toxicology data, which aren’t always available for reproductive, neurodevelopmental, immunological, and other noncancer effects, he says.

The FDA did begin looking beyond cancer about a decade ago when it examined the cardiovascular effects of trans fats. Trans fats, or partially hydrogenated oils, were a wake-up call, because the agency has traditionally looked at the cancer risks of food chemicals, Musser said. The FDA declared in 2013 that partially hydrogenated oils are not GRAS because of evidence linking consumption to an increased risk of heart disease. Two years later, after much pushback from the food industry, the agency finalized that determination.

Today, the FDA is grappling with the potential cardiovascular effects of another food chemical—the low-calorie sweetener erythritol, a sugar alcohol.

The agency is also concerned about early-life exposures and developmental toxicity, as those effects have the biggest impact on public health, Musser said at the IAFNS meeting. In 2021, after a congressional report revealed harmful levels of toxic heavy metals in many foods consumed by babies and young children, the FDA launched a program called Closer to Zero. The effort aims to reduce levels of arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury as much as possible in foods consumed by children to address neurodevelopmental concerns.

Knowledge about the effects of chemicals on biochemical pathways that can lead to adverse health outcomes is growing rapidly. “We’re moving into a very molecular approach to looking at the function of some of these chemicals, whether it be drugs, natural supplements, or food additives,” Musser said at the IAFNS meeting. “Our understanding of those pathways is continually changing.”

The food industry welcomes the FDA’s move to unify its food safety efforts. Both industry and consumer advocacy groups criticized its initial plan for not giving the deputy commissioner complete authority over food safety. The FDA addresses that concern in its June 27 update.

“We are pleased the FDA is taking bolder action to make meaningful and lasting change by answering informed industry and stakeholder calls to unite and elevate the Human Foods Program and fully authorize the deputy commissioner with control over its strategic direction,” Sarah Gallo, vice president of product policy at the Consumer Brands Association, says in a statement. The trade group represents food, beverage, and household product manufacturers.

The FDA plans to release final details on the proposed reorganization this fall, including an established budget. Congress will then have 30 days to raise any concerns. The FDA says it will continue to engage with stakeholders throughout the process.

The approach will be modeled after the Closer to Zero program, including frequent communication and engagement with industry and advocacy groups, Musser said. “Recently we’ve learned just how much misinformation is out there about the hazard of particular chemicals,” he said. “Communicating risk here is going to be a challenge for the agency.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter