Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Forensic Science

Extended wash removes drug contaminants from forensic hair samples

Mass spectrometry method on individual hairs can distinguish zolpidem contamination from ingested drug

by Louisa Dalton, special to C&EN

March 22, 2019

An investigator who wants to figure out if drugs contributed to a crime will likely collect hair samples from the person of interest. As hair forms in the follicle, drugs in the bloodstream slip into the hair cortex, creating a unique tool for measuring drug intake.

But the drug is often also present in that person’s environment and could contaminate hair from the outside. A new analytical method does a better job at distinguishing between ingested drug and hair contaminant. Researchers closely investigated single hairs with mass spectrometry and tracked how well an extended wash removed external traces of the drug (Anal. Chem. 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05866).

Before testing hair samples, analysts try to decontaminate them by washing with one of many different protocols. The decontamination strategies vary widely, with no established gold standard. Researchers know that most protocols do not completely remove contaminants, and some procedures may even further incorporate contaminants into the hair shaft.

Markus R. Baumgartner and Thomas Kraemer of the Zurich Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Zurich and colleagues took an in-depth look at single hairs so that they could get to the root of contamination. The researchers chose the sleep aid zolpidem (Ambien) for their study because high-resolution mass spectrometry can detect small traces of the drug. Abuse of zolpidem can impair driving.

To do routine hair analysis, researchers pulverize locks of hair, approximately 50-70 strands at a time, and examine them with liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. In this experiment, however, they sliced individual hairs lengthwise to gain a look at a stretch of the inner hair shaft. They scanned sections about 5 cm long with ultrasensitive matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry.

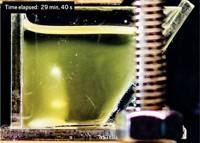

To test environmental contamination, they soaked hair strands in a solution of zolpidem for an hour and measured the levels of zolpidem both outside and inside the hair shaft. Then they treated the highly contaminated hair with five different washing protocols: two suggested methods from papers, one recommended by the Society of Hair Testing, another by the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime, and one that their group developed. The first four washes involved successive, short rinses in alcohol, buffer, or organic liquid. Their wash, which they wrote was “carried to the extreme,” added an extra 18-hour soak in methanol.

Zolpidem levels went down every time, yet only the extreme 18-hour wash developed by this team removed the zolpidem completely from both the hair shaft’s interior and its surface.

Advertisement

Next, they measured zolpidem amounts in hair samples from longtime, regular users of the drug. Their hairs showed high levels of zolpidem inside the hair, and much lower levels on the outside. The researchers submitted these to the 18-hour wash. Zolpidem from the outer layer of the hair was completely stripped away, yet inner levels remained high. Not even the extreme wash could remove zolpidem from the inner hair shaft of regular users of the drug, implying strong bonding interactions in the inner compartments.

Olaf H. Drummer, a forensic pharmacologist at Monash University, says that the group’s innovative methods do appear to show that contamination “may be distinguishable from actual uptake of drug, at least for zolpidem.” He adds that the method, of course, has to be confirmed by other labs and for other drugs. In particular, he wonders whether the contaminant would still wash out if it stayed on the hair for longer than an hour before washing. Baumgartner, Kraemer, and coworkers are now working on discerning cocaine contamination in single hairs with this method.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter